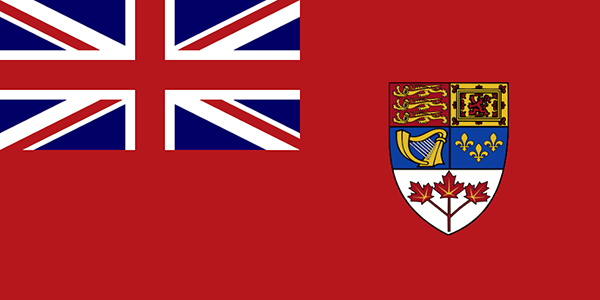

1964 design featuring Alan Beddoe’s 13-point leaf, the Union Jack and the Fleur-de-lis.

Pearson was determined to give Canadians a distinct flag that didn’t advertise clear-cut ties to Britain — and pushed for his own simple tri-leaf draft, which still used the Imperial red, white and blue, as a means of inspiring greater national unity. At least at the time, his vision had the opposite effect. John Diefenbaker, head of the Conservative opposition, continued to fight ferociously for a flag that explicitly showed the country’s British heritage: for him, the only reasonable option was the Red Ensign. In French Canada, meanwhile, the flag debate roused little enthusiasm; Pierre Trudeau noted that “Quebec does not give a tinkers dam about the new flag, it’s a matter of complete indifference.”

Pearson’s very democratic multi-party flag committee favoured the single maple leaf category (the other two groups were for reworkings of the Red Ensign and multiple leaves), but even the one-leaf designs came in an array of different styles and colours. And for many of the Liberals, New Democrats, old nationalists and a new generation of post-war Canadians, even the pairing of the Union Jack and Fleur-de-lis did not quite represent Canada. As Pierre Sévigny, the former Progressive-Conservative MP for Longueuil, said at the time, “Neither the … Union Jack nor the Fleur-de-lis can be accepted as national emblems by more than a minority of Canadians.” Canada needed, and would get, a symbol all its own.