People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

The story of a biologist’s lifelong study of an endangered species — and its future

One of the rare disagreements between my parents came early in their marriage. My dad, George Mitchell, a biologist, had shot a magnificent buck pronghorn, had had its head taxidermied, and then wanted to give him pride of place in my mother’s elegant living room.

My mother, Constance Mitchell, a modern painter who carefully curated her surroundings, was horrified. Immune to Dad’s protestations that this pronghorn was, as he wrote in his journal, a “museum-quality specimen,” she banished the stuffed beast to the rec room in the basement where it promptly became a quizzical witness to our family life. It was so lifelike that it often seemed to me it was simply passing by and had thought to poke its head through the wall, keen to see what we were watching on television.

Dad was right about one thing. Pronghorns are majestic to begin with, but this fellow was something special: inky Y-shaped horns as thick as my wrist, square snout splotched with black, supersized dark eyes tipped with long lashes, a pair of white chevrons running down the buff of his throat. Even after decades on the wall, his ears were pricked so high I could almost feel him listening in on our conversations.

My dad, who died in June 2017 at 91, loved that pronghorn. But not just that one. He loved the whole species, Antilocapra americana. In his 1980 book, The Pronghorn Antelope in Alberta, my dad refers to his passion as an affair of the heart that never lost its fire. Maybe it was the lure of the unknown. The pronghorn was a scientific mystery when my dad was hired as the Alberta government’s first game biologist in 1952 and began to study it.

Even the basics were obscure. At what age did pronghorns begin breeding? How many young did they have? What did they eat? How did they survive the winters? How many were there in Alberta and Saskatchewan, the very northernmost tip of its continent-wide range? How many had there been? All unknown. But unless you knew this most elementary information, how could you predict whether they would stick around? He set about the messy, painstaking, life-consuming business of finding out.

***

The pronghorn’s ancestor evolved in North America around 25 million years ago. Eventually, that ancestor, Merycodus, spawned a family of about a dozen species of hooved grazers from one the size of a jackrabbit to the lone, big survivor that became swift enough to race the hungry cheetahs and fearsome hyenas that then populated North America.

But while the cheetah, hyena and all the other pronghorn relatives died out in North America — the pronghorn’s closest genetic relative today is the giraffe — Antilocapra americana triumphed. And while it is the fastest land-runner in the Western Hemisphere, clocked in a sprint at 100 kilometres an hour, its unique gift is its ability to go the distance, literally and metaphorically. It has an uncanny ability to convert the oxygen in its muscles into velocity, to keep up a car-level pace for 10 minutes.

The pronghorn survived not only the climate stresses of the ice age, but also the arrival of humans, becoming the main grazer of the North American Great Plains. Its range exceeded even that of bison.

Theodore Roosevelt, 26th president of the United States, was fascinated with what he often called the prong-horn antelope, writing about its tremendous speed, sharp sight and sweet meat. But he confessed himself baffled by its behaviour.

“Antelope possess a most morbid curiosity,” he wrote in his 1885 book Hunting Trips of a Ranchman. “The appearance of any thing out of the way, or to which they are not accustomed, often seems to drive them nearly beside themselves with mingled fright and desire to know what it is, a combination of feelings that throws them into a perfect panic, during whose continuance they will at times seem utterly unable to take care of themselves.”

All hunters had to do to attract a pronghorn in those days was wave a red handkerchief at it, Roosevelt writes, and, fatally inquisitive, it would draw ever nearer, stamping and snorting, until it got within rifle range.

By the time my father was born in 1925, the pronghorn was near extinction. From a North American peak population of about 35 million a century earlier, the species was reduced to as few as 13,000, says John Byers, a zoologist at the University of Idaho who has studied the animals for 35 years. That’s a drop of 99.996 per cent.

The reasons? It was hunting, some of it to feed a trade exporting wild meat to Europe; it was the campaign to rid North America of wolves, grizzlies and cougars, because when they were gone, the coyote reigned to feast on pronghorn fawns; it was the miserable cold and deep snow that plagued the start of the 20th century.

And it was fences. Although pronghorns can jump — Byers has seen one jump over a human — they choose not to. They always think there’s another way around. But as the Prairies became more settled, fences began to abound. Pronghorns, many of which migrate hundreds of kilometres a year seeking food, could no longer get through.

When my dad started studying them, their numbers had crept up thanks to a continuous closure on pronghorn hunting, but they were still in considerable peril. I spent my childhood summers scanning the Prairies for them. My family would be driving along the Trans-Canada Highway from Regina, where my dad began teaching at the university in 1966, to the Pacific Ocean — “the coast,” we called it.

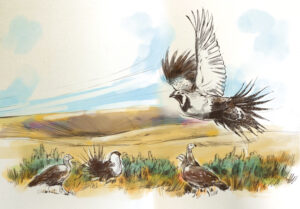

Pronghorns travel in herds, white bums flashing, legs seemingly too spindly to hold up their robust bodies, terribly alert. Every time I saw them then, I was overcome with wonder at their synchronized speed. I had no idea that they had once been so much more plentiful. And despite my dad’s chops as an ecologist, I had no idea then that pronghorns are remnants of what was once a far richer dance of life on the Great Plains, with the extinct pronghorn kin and cheetahs and hyenas, but also dire wolves, giant short-faced bears, lions, jaguars, mastodons, woolly mammoths and ground sloths, among many others.

“In the hurtling pronghorn, the vanished predators have left behind a heartrending spectacle,” writes the journalist William Stolzenburg in his 2008 book Where the Wild Things Were: Life, Death, and Ecological Wreckage in a Land of Vanishing Predators. “Through the smoking displays of wild abandon runs a desperate spirit, resigned to racing pickup trucks in its eternal longing for cheetahs.”

Biology was different when my dad was doing it. Nature’s rules were there to be cracked like a code, parsed, catalogued and marvelled at, species by species. They were timeless certainties, revealed if only one were intrepid enough. Today, the fable of immutability has long been abandoned. Now, the overriding scientific narrative is to figure out what the rules used to be and how they’re changing.

The great pulse of carbon dioxide our species has been putting into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution has pushed the planet’s chemistry to where it hasn’t been for tens of millions of years. That brings disruption to weather patterns, precipitation, temperature norms, ice cover and ocean acidity. And today, to assess the effect those changes have on animals, biologists prefer to observe them live, mainly in the wild, often across ecosystems.

When my dad began studying them, focusing on a single species was the norm. Killing was expected. Biologists were collectors and archivists, preferably of enough samples to compare. It was pretty crude. One of my dad’s slender roster of published scientific articles describes how he and a co-author sifted through 162 litre-sized samples of pronghorn stomach contents, a bid to see what the creatures liked to eat. It involved washing and sieving the partly fermented food — cud, you would call it in a cow — then drying it on a towel and identifying it. Silver sagebrush and pasture sagewort are the preferred foods in southeastern Alberta, it turns out.

Dad also tried to figure out how old a pronghorn was, a basic piece of information that let him determine how many adults compared to yearlings compared to newborns there were in an area, and try to work out what proportion of each made a healthy population. The traditional way was to examine wear on teeth. My dad, never one to take the easy route, and his grad student Larry Kerwin tested the old method’s accuracy by counting annual bands of cementum covering the root of a pronghorn’s tooth.

Turned out, that was far more accurate. And this line from another article gets me: “The incisor teeth used in this study were extracted from 190 mandibles obtained by [George Mitchell] from mature pronghorn antelopes harvested in Alberta during the 1961-64 hunting seasons.” That’s a lot of corpses from a lot of hunters. And it was a lot of work after that. To get the incisors out cleanly, Dad boiled every mandible in a pot of water for 45 minutes. At some point in the process — post-skinning or post-boiling, I suppose — he would hang the jawbones on the back fence to dry. One day my mother got a sniffy phone call from a neighbour. She was having people for dinner. Could the mandibles please be removed from the fence?

Little did the neighbour know what went on inside the house. It wasn’t just the pronghorn head on the wall, or the bits and pieces of pronghorn carefully bagged but nauseatingly identifiable in the family freezer — “You never knew what you were going to find in there,” my mother told me recently. “When I look back on it, I was terribly good natured.” — but also the rows of pronghorn antelope fetuses suspended in formaldehyde in the Mason jars that lined my father’s home office.

I used to look at them for hours, unable to stop thinking about the dead mothers they had come from, targeted because they were pregnant, wombs ripped open for their contents. They had been collected in aid of another of my dad’s findings — pronghorns conceive as many as nine young at a time, but only the two strongest survive. Further research by an American colleague of my dad’s revealed that the most ambitious of those embryos get rid of their siblings by stabbing them to death — the conniving twins practising fratricide in utero. It was positively mythic.

Pronghorns are remnants of what was once a far richer dance of life on the Great Plains, with the extinct pronghorn kin and cheetahs and hyenas, but also dire wolves, giant short-faced bears, lions, jaguars, mastodons, woolly mammoths and ground sloths, among many others.

Over the years as a science journalist, I’ve thought a lot about the theory that a scientist falls in love with a subject because it either embodies the scientist’s personality or repudiates it.

For my dad, it was the former. Like the pronghorn, he had no siblings and few relatives. I think he felt like an outsider, born to a teenaged mother forced to marry his father because of him. They divorced when my dad was five, rare in Canada in 1930.

He was smart and graceful and devilishly hard to catch. I remember the tales he told of running feral in the Depression-era streets of Vancouver, stealing apples from the trees with impunity. A survivor, certainly, and perhaps an unlikely one. His father got custody of him — a bigger scandal than the divorce — and his father’s mother, blind from diabetes, tried to raise him. He used to talk about her attempts to sterilize needles in boiling water before injecting insulin, and about how she made him get coal from the half-cellar where the rats were almost as big as he was.

His saving grace, in a bizarre way, was the Second World War. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force the minute he could and, with that binocular eyesight that could eventually spot a pronghorn at impossible distances, he trained for battle.

The war ended before he got overseas, but along with his discharge, he got a ticket to university. The first in his extended family of Scottish immigrants to attend university, he went on to get a PhD — on the pronghorn. To the end of her life, his mother lamented that he had never had a profession like her sister’s son Doug, the fireman.

But I think it was the elegance of the pronghorn that really captured him. He longed for it. My mother said he brought home some young pronghorns and tried to raise them at the university, but couldn’t get the milk formula right. They died of the scours.

Today, the pronghorn is hailed as one of North America’s conservation success stories, a species brought back from the brink. Its global population is about 850,000. That makes it a species of “least concern” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the organization that compiles the red list of threatened species.

Yet the biologists who study the pronghorn today are concerned about its future. A recent study of 18 pronghorn communities at the bottom of the species’ range in the southwestern United States concluded that most of them will die out in that part of the country in a few decades as the climate changes. That was a phenomenon few scientists even imagined 100 years ago.

Half the world’s pronghorn population lives in Wyoming, because it alone in the Great Plains is lightly farmed. But with climate change, Wyoming is likely to become less hospitable for pronghorns. Even now, almost all the ancient, narrow migration routes pronghorns once used in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which takes in part of Wyoming, are choked off by human activity, says Mark Hebblewhite, a professor of ungulate ecology at the University of Montana in Missoula.

That matters, because animals that like to migrate but cannot are generally less healthy, he says. The ones that are still migrating are at a higher risk in general because they interact with more habitats and likely more human effects on those habitats. So, pronghorns will be hit with a double whammy.

Ultimately, climate change may mean more pronghorns come to graze in Canada as grasslands are pushed farther north. Already they have been spotted near Edmonton, a more northerly address than they have had for years. Whether they will also be able to return south to escape ferocious winters is an open question. And there are plentiful barriers within the vast Canadian landscapes the pronghorn craves. More farms, more ranches, more roads and more fences mean less running room. Less ability to go the distance, if you will.

Hebblewhite wonders how climate change, with its weather extremes, combined with all those barriers will affect the pronghorn. For example, in the bitterly snowy prairie winter of 2010/2011, pronghorns died by the thousands because they pushed too far south in search of less snow and more food, crossing Montana’s Fort Peck Reservoir. Once the reservoir melted in the spring, the pronghorns, poorer swimmers than jumpers, were stuck.

In all, as much as 80 per cent of the pronghorn population north of the Missouri River died that winter, including many that would have migrated to Canada, says Hebblewhite. To be sure, the population rebounded quickly and is now almost recovered. And scientists, including those with the Wildlife Conservation Society in the U.S. and the Alberta Fish and Game Association, are mounting programs aimed at modifying fences to allow pronghorns to wiggle underneath and preserve migration paths. Yet, it’s believed that less than five per cent of fences along pronghorn travel routes are modified, says Andrew Jakes, regional wildlife biologist for the National Wildlife Federation in Missoula, Montana.

Will any of my dad’s pioneering work help the pronghorn survive its next set of challenges? Jakes says my dad’s holistic work on the species “moved the needle forward” on its conservation in Saskatchewan. I know Dad had a lot more research about his beloved pronghorns and other Prairie creatures in notes that he never wrote up into scientific articles.

He tried. Long retired, his papers stacked in two tightly packed sheds in the backyard of our house in Regina, he would sit at the dining room table, surrounded by his data, trying to make enough sense of it to publish. Finally, he was diagnosed with dementia. My mother sold the big house and bought a condo for them at the coast. My older sister and I flew out to help them clean out the sheds.

He stood there, a frail figure with arthritic hands, his khakis impeccable, hair and moustache smartly trimmed, sifting through a single file folder for hours, trying to understand what his old notes meant. We finally took the whole lot to the university archives.

My mother shipped the pronghorn head with them to B.C., although she never hung it up again. I’m not sure he noticed. By the time my mom threw a posh summer bash for her 80th birthday at a rented mansion near Victoria, things were starting to unravel. At one point my dad seemed a little lost. One of my cousins turned to him and said: “So, you were a biologist at the university, George!” My dad, who had lived and breathed biology for more than six decades, looked thoughtful for a moment and said: “Was I?”

The head did not survive Dad’s move to the nursing home a few years later. My mother arranged for it to be shipped back to Regina to the Royal Saskatchewan Museum, hoping that, still magnificent although missing one glass eye, it could go on display to honour my dad’s work.

I checked recently. Alas, we couldn’t provide accurate enough details of where and when my dad had shot it and, without that provenance, the head was useless. I’m told it was incinerated.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the May/June 2018 Issue

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

Places

“All the mischiefs humans and the universe are capable of inflicting on an ecosystem have conspired to attack the prairies.”

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it

Wildlife

This past summer an ambitious wildlife under/overpass system broke ground in B.C. on a deadly stretch of highway just west of the Alberta border. Here’s how it happened.