People & Culture

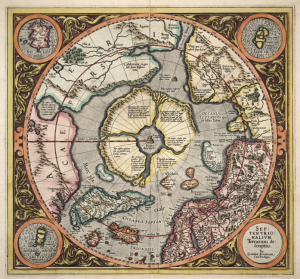

On thin ice: Who “owns” the Arctic?

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

- 4353 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Environment

After two months of Arctic night, bracketed by brief windows of expanding twilight, the sun makes its annual return above the crest of the mountains surrounding Tromsø, Norway, on January 21. Locals mark the occasion with a traditional treat of “sun cakes,” a kind of raspberry-filled Norwegian doughnut.

The officials who conceived of an Arctic Frontiers conference hosted at this time in this affluent, modern city of 75,000 no doubt relished the symbolic value. Yet this year, at least, most attendees — a robust mix of local and international scientists, politicians, Indigenous leaders, policy makers, businesspeople and students — missed the magic moment, absorbed in opening-day discussions indoors. Ironic? Maybe. Appropriate? Entirely. For in contrast to “sun day’s” clockwork predictability, their agenda was dominated by the uncertainties and change — climatic, environmental, social, technological, economic and political — now disrupting the polar region.

I attended this year’s forum, Arctic Frontiers’ 13th, for Canadian Geographic, hoping to gain a greater understanding of the scope and urgency of these issues — both from the perspective of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Arctic residents, and for the rest of the world looking in. Participants hailed from the Arctic Council’s eight member countries — Canada, Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States — six permanent participant Arctic Indigenous communities and other observer nations. The 2019 theme was “Smart Arctic,” but the breadth and depth of their discussions, which spanned four days, defy easy summary. Even so, snippets of important stories and portraits of an Arctic in profound transition emerged — useful frames of reference for those who want to go deeper in any given area. Their nature and significance are encapsulated in the five themes outlined below.

Michael Byers, a professor of political science at the University of British Columbia whose focus includes Arctic sovereignty, prefaced his plenary remarks by noting he’d started the day on a boat in the ice-free waters off Tromsø. Byers reminded the audience that in January in Canada at this latitude — 69°40’58” north, roughly in line with Igloolik, Nunavut — winter conditions are much harsher and more extreme. The explanation, of course, is that Norway’s coastal climate is moderated by the Gulf Stream. It’s why a city such as Tromsø, which hosts a university, a big arts community, hotels, large tourism and government sectors and the Arctic Council secretariat, exists. But it also means every discussion of the Arctic needs to bear in mind that it is far from homogenous. This applies not just to climate, but to politics, economics, population and culture; it even extends to the way data about these things are gathered and interpreted, said Ingrid Lomelde, policy director at World Wildlife Fund Norway.

Speakers at the conference also stressed that differences exist within regions, too. According to Klaus Dodds, a geographer and geopolitics professor at Royal Holloway, University of London, much of that is driven by the legacies of settler colonialism as well as gender and infrastructure inequality. Consequently, in calling for a “Smart Arctic,” he advised the audience: “We can’t talk about the Arctic singular. We have to acknowledge and recognize that we are always talking about multiple Arctics — geographically varied, but also very varied and intersectional.”

Tore Furevik, an oceanographer from the University of Bergen and director of the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research, opened his plenary statement with an incredible statistic: “Since satellite measurements began 40 years ago, the Arctic has lost 10,000 tonnes of sea ice — every second,” he said. “And the rate of ice loss from Greenland is about the same.”

Human-induced global warming is the cause, of course — compounded by the fact that air and ocean temperatures in the Arctic are increasing twice as fast as for the planet overall. And many of the high-profile impacts are familiar. Less ice cover (even thinner ice) makes Arctic waters more accessible to shipping, energy development, industrial fishing and militarization, with their secondary consequences; it disrupts the ecology for species such as polar bears and seals, which rely on ice for feeding and reproduction; it has a dramatic impact on global weather patterns due to its changing influence on heat, water and energy circulation in both the ocean and the atmosphere; and, in the case of melting land ice, raises sea level.

For at least one presenter at the conference, however, no impact is more profound than that on Indigenous Peoples, and in particular the Inuit. “Inuit have been living in the Arctic on the sea ice for centuries, if not millennia,” said Trevor Bell, a geographer at Memorial University of Newfoundland, stressing that as well as being an essential platform for hunting and travel between communities, ice is “part of their identity, it’s part of their culture.”

Bell is no passive observer. Instead, he is the co-founder of SmartICE, an award-winning sea ice monitoring and information service that began as a community research project in Nain, Nunatsiavut (in Newfoundland and Labrador), and Pond Inlet, Nunavut, and is now expanding throughout the Canadian Arctic using a social enterprise model. The system consists of sea-ice thickness sensors embedded in locations chosen by local Inuit which then feed data on thickness, temperature and other variables via satellite to portable readouts on snow machines and computers at home. “The technology is designed to augment, not replace, Inuit traditional knowledge of the ice,” said Bell.

SmartICE is an important story on many levels, providing safer travel, technology training for youth and commercial opportunity. But its essential impetus — that, in Bell’s words, “sea ice is failing” the Inuit and, in turn, “impacting their mental health, physical health and every part of their cultural fabric” — potentially applies to Indigenous Peoples across the Arctic.

The Ottawa Declaration, which enshrined the formation of the Arctic Council in 1996, explicitly recognizes “the traditional knowledge of the Indigenous people of the Arctic and their communities” and takes “note of its importance.” Not surprisingly, then, many discussions at the Arctic Frontiers forum touched on and, in some cases, focused on Indigenous knowledge. More unexpected, however, is that those discussions were sometimes geared more toward making the case for its value and legitimacy than exploring the insights Indigenous knowledge brings to specific topics. Even in this forum, then, which was created to link policymakers and business with the science community to foster responsible and sustainable development of the Arctic, in practical terms Indigenous knowledge is not always an equal partner at the table.

“We’ve had difficulties with the acceptance and the understanding of Indigenous knowledge by many scientists. Hopefully we can eventually turn the corner and ensure that there is legitimacy and respect for and recognition of the value of Indigenous knowledge,” said Dalee Sambo Dorough, chair of the Inuit Circumpolar Council, in her opening remarks at a session called “The Power of Knowledge.” Dorough, who is also an assistant professor in the department of political science at the University of Alaska Anchorage and former chairperson of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous issues, used her allotted time to address “the power of Indigenous knowledge.” She described it as “a highly developed, highly sophisticated and detailed understanding of, in our case, Arctic conditions, based upon a profound and intimate relationship with the environment, observations and an understanding of the living creatures and their relationships to this environment,” adding that “there is a need for both Indigenous knowledge as well as science.”

Aili Keskitalo, president of the Sámi Parliament of Norway, a representative body for the Indigenous Sámi people, speaking on a panel in the same session, joined Dorough in linking the application of Indigenous knowledge to the Indigenous right of self-determination. This, after fellow panelists Lisa Murkowski, the United States senator for Alaska, and Ine Eriksen Søreide, Norway’s Foreign Minister, spoke about difficulties Arctic residents face in making some decision-makers in the South aware of the scale of the problem of climate change in the Arctic. Keskitalo’s reply: “It’s true that Indigenous voices are not heard by decision makers. That can be fixed. By making us the decision makers.”

An important corollary complicates this subject — the fact that many non-Indigenous Arctic residents also believe that outsiders have a greater influence than locals over what happens in the region. Conference host Willy Ørnebakk, chair of the Troms County government, got this on the table right at the outset in his opening remarks, when he praised local “Arctic know-how” and declared: “The driving force in future development should be people living in the region, not workers flown in one day and out the next.”

Often, that external influence spills over into something more destructive. “Outsiders have been exceptionally good at exploiting [local] smartness,” said Klaus Dodds. “Every community will tell a story of feeling used and abused when it comes to Arctic smarts.” In a nod to this year’s “Smart Arctic” theme, he said instead of talking about knowledge economies, he prefers the term knowledge “solidarities,” which means: “Are we co-producing that knowledge, are we co-circulating that knowledge, are we co-consuming that knowledge and, to be honest, who is making money from that knowledge?”

In a related exchange, John-Arne Rottingen, chief executive of the Research Council of Norway, was asked if his organization had formal ways of incorporating Indigenous knowledge into its work. It does, he said, but then added: “I wouldn’t differentiate necessarily between Indigenous people and other people. I think there’s a commonality in actually involving [all] people…, Indigenous and others, in deciding what are the most important research questions, understanding their often-tacit knowledge, knowledge that is not codified. Indigenous Peoples have that knowledge, but also other people.”

The last word here went to Dorough, who acknowledged Rottingen’s point on inclusion, but reasserted the distinctions between local and Indigenous knowledge — based both on the longevity and nature of the Indigenous relationship with the Arctic environment and also the law. “You probably have a legal obligation to be responsive to Indigenous Peoples,” she said. “There are solemn commitments governments have made.”

As you’d expect of a conference themed “Smart Arctic,” technology received plenty of attention. Speakers talked about its potential to boost and diversify local economies, to alleviate social strife by improving education, retention of language and culture, and reducing the brain drain (particularly among young women, who typically get more education than young men in much of the Arctic, and often leave their communities in the process), and to help in monitoring and responding to changes in the local environment.

Achieving these goals, however, remains impossible where there is little or no high-speed, high-bandwidth Internet and data access. Ken Coates, a professor at the University of Saskatchewan who specializes in regional innovation, Indigenous and northern Canadian issues, told the conference that Internet in the Canadian north is five to 10 years behind the south. Nettie La Belle-Hamer, deputy director of the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute and director of the Alaska Satellite Facility, said the lack of high-volume, high-speed data service in the American Arctic, combined with other social and economic characteristics, puts it in the developing country category.

Changes are happening. In Alaska, the current rollout of the first broadband fibre network to service the state’s north coast stands to be “a major game-changer,” La Belle-Hamer said. And there and elsewhere, satellite communications, which is being aggressively deployed in Northern Norway, has similar potential.

But infrastructure alone is not a panacea, cautioned Coates. “The idea that everything’s going to be smart doesn’t mean it’s going to be favourable,” he said.

Some downsides are foreseeable — automation, e-commerce and e-banking have the potential to undermine communities by causing the loss of physical stores and banks, for example. But other impacts might be unexpected. Coates cited the example of using improved data access to expand telemedicine services for treatment of diabetes, a widespread health problem in the North. While it’s making people healthier, it also then means there is less demand for flights out of the community to see doctors farther south. While that’s good for public health and cost savings, it turns out the local airlines’ economic viability hinges on running a certain number of those flights. As they dry up, airlines must reduce service and potentially go out of business. This hurts communities in turn.

Disruption wrought by a changing climate is the catalyst or a defining factor for nearly everything on the Arctic Frontiers’ agenda. For this reason, the presentation by Martin Sommerkorn, head of conservation for the World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic Program and coordinating lead author of the polar regions chapter in the IPCC’s upcoming Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, was a signature session.

His talk was a call to heightened action, based largely on the data, trends and underlying science cited in the IPCC’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C published last fall. In stressing the key point that a 1.5 C planetary warming means 3 C to 4 C warming in the Arctic, he managed to both amp up the urgency while adding a helpful perspective: “If you manage to change the trajectory of the Arctic, it will change everything.”

Even the best-case scenario still means big changes are in store, however, particularly for ocean ecosystems — over and above the ice loss cited earlier. Given that many nations, and host country Norway in particular, are looking at the changes not merely as a source of concern but also a potential opportunity to expand resource and fisheries development, a couple of Sommerkorn’s specific points stood out.

The first relates to the ocean’s absorption of global CO2 emissions. According to Sommerkorn, polar seas have taken up 25 per cent of humanity’s CO2 emissions in the past 50 years. While this has done a lot to lessen the rate of atmospheric heating, it has also caused increased ocean acidification, which is “very much an Arctic problem,” he said. The chief concern is that “in the very sensitive ocean ecosystems of the Arctic…many food chains rely on calcification, which is endangered with acidification.” How dire is that? If current trends continue, he said, by 2030 the surface saturation state for argonite (an indicator of carbonate ion concentration) is expected to fall below critical thresholds necessary for many shellfish and plankton species’ shell and skeletal formation.

At the same time, increases in water temperature are causing fish species to move farther north. Aili Keskitalo of the Sámi Parliament of Norway noted this earlier in the conference for its impact on the small-scale Sami fishery. “The species we have traditionally fished are moving away from the coastline and are no longer accessible,” she said. “Mackerel are replacing them, and it is forcing us to change our diet.” However, the impact on the migrating fish may be even more severe, said Sommerkorn. “We will see thresholds crossed as species will lose their habitats as they cannot go farther north.”

The sum of these changes has implications “for regional renewable resource economies, food security, health and cultural identity of Arctic peoples and the global supply of shellfish and fish,” said Sommerkorn.

As such, it’s also a microcosm of the entire Arctic Frontiers’ agenda and experience — changes local and global, intertwined.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

People & Culture

In this essay, noted geologist and geophysicist Fred Roots explores the significance of the symbolic point at the top of the world. He submitted it to Canadian Geographic just before his death in October 2016 at age 93.

Environment

Warming trends continue due to human-caused climate change

Environment

The Royal Norwegian Embassy and the Royal Canadian Geographical Society teamed up for two days of talks on the future of the Arctic and the “blue economy” in Norway and Canada