Kids

Giant floor maps put students on the map

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

- 1487 words

- 6 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Mapping

New estimates of how much groundwater exists in the top two kilometres of Earth’s landmasses are shedding light on the depletion of the world’s accessible reserves, according to a new study by Tom Gleeson, a University of Victoria hydrogeologist.

Gleeson’s findings, published recently in Nature Geoscience, reveal that a boggling 22.6 million cubic kilometres of water lies beneath the Earth’s surface. The amount is based on exhaustive analysis of geochemical, geological, hydrological and geospatial data sets with groundwater simulations. But most importantly, according to Gleeson, the team has been able to estimate that less than six per cent of that total (and more likely in the range of 350,000 cubic kilometres), is renewable, or “rechargeable,” within a 50-year time span.

Interestingly, Gleeson told the Canadian Press, “this ‘modern’ or ‘young’ groundwater is in fact three times larger than the volume of all the other freshwater in the Earth.” To picture that, he notes in the study, imagine covering the continents in three metres of water.

Canada alone has reserves of 70,000 cubic kilometres of water in the 200 metres nearest the surface, estimates Alfonso Rivera, chief hydrologist for the Geological Survey of Canada, and editor of the 2014 book Canada’s Groundwater Resources. That’s about three times as much water as is held by the Great Lakes, which make up one-fifth of the world’s surface fresh water.

The 50-year span — what Gleeson calls a “human lifespan scale” — is crucial. More than a third of the world’s population depends on groundwater, including roughly a third of Canadians, and the resource is not evenly distributed, or used, across the continents.

In places such as droughty California and the American Midwest, unsustainable groundwater use is already leading to land subsidence, saltwater intrusion and contamination, says Rivera. Much of the groundwater being used in these regions is thousands of years old, and cannot be recharged in many, far less one or two human lifetimes.

“If we collect more data,” said Rivera, “so we’re better able to measure how much we have and where, what we use and how vulnerable it is, we’ll be better off than anywhere else.”

Gleeson’s study, meanwhile, is a major step in this direction. “The biggest implication,” he told the Canadian Press, “is that these young groundwater resources are a finite resource that we need to protect and manage better.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Kids

Canadian Geographic Education’s series of giant floor maps gives students a colossal dose of cartography and is a powerful teaching tool

Mapping

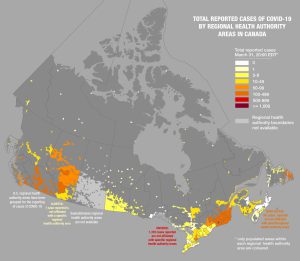

Canadian Geographic cartographer Chris Brackley continues his exploration of how the world is charting the COVID-19 pandemic, this time looking at how artistic choices inform our reactions to different maps

Mapping

Maps have long played a critical role in video games, whether as the main user interface, a reference guide, or both. As games become more sophisticated, so too does the cartography that underpins them.

Mapping

Canadian Geographic’s cartographer explores how media, scientists and citizens are charting the coronavirus pandemic