Environment

The sixth extinction

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

- 4895 words

- 20 minutes

Science & Tech

Consider this the next time you look in a mirror: there are as many microbial cells in your body as there are human cells, meaning you’re not just an individual person; you’re an entire ecosystem, providing habitat for an incredible array of microscopic biodiversity.

Wait — before you click away in disgust and go take a Lysol shower, what if we told you that the bacteria, fungi and even parasites that inhabit the human body actually play an important role in regulating its functions? Science is beginning to gain a better understanding of how our “microbiome” protects us from disease, aids in digestion and even influences our mood and behaviours.

The remarkable geography of the human body is the subject of a new exhibit at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa. Originally developed by the American Museum of Natural History in New York City and now in Canada for the first time, Me & My Microbes: The Zoo Inside You explores how our microbiome develops and changes over our lifetime, beginning from the moment we’re born. In fact, a healthy coating of microbes is often a mother’s first gift to her baby: bacteria from the birth canal provide the foundations for an infant’s digestive and immune systems. (If you were a C-section baby, don’t worry; your microbiome probably caught up by the time you were a toddler.)

As we grow and interact with our environment, different bacteria continue to colonize different areas of our bodies, shaping aspects of our physical and mental health. Where we’re born, what we eat and our biological sex all help determine the makeup of our microbiome.

The human immune system has evolved to neutralize harmful pathogens before they make us really ill, but sometimes it does its job too well, attacking proteins from food (resulting in an allergic reaction) or even the body’s own cells (resulting in an autoimmune disorder). The presence or absence of certain bacteria in our gut can impact our tendency to gain or lose weight, our ability to process certain foods, and levels of the mood-regulating chemical serotonin, suggesting a link between our microbiome and our relative risk of obesity and depression. Recent studies have even raised the possibility of a connection between the gut microbiome and autism spectrum disorder.

Given the microbiome’s outsized influence on our health, Dr. Kathy McCoy, scientific director of the International Microbiome Centre at the University of Calgary, calls it “our forgotten organ.”

The Centre, which advised on the exhibit and a series of “Gut Talks” coming to the museum in the new year, aims to crack the code of the microbiome to prevent chronic illnesses before they begin.

“We are as much microbial as we are human, so I believe this is one of the most important areas of research we should be focusing on in human health,” says McCoy.

The Centre’s germ-free facility is unique in Canada and is presently investigating the human microbiome in early life through a comprehensive study of 1,000 babies born in Alberta.

Me & My Microbes is on at the Canadian Museum of Nature from Dec. 20 to March 29, 2020.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

Environment

As the impacts of global warming become increasingly evident, the connections to biodiversity loss are hard to ignore. Can this fall’s two key international climate conferences point us to a nature-positive future?

Wildlife

By understanding why animals do what they do, we can better protect them while making people care

History

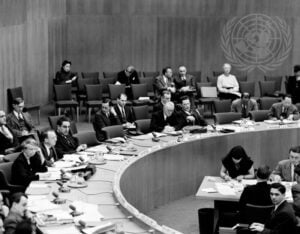

On Dec. 10, 1948, the United Nations adopted an aspirational document articulating the foundations for human rights and dignity, but who was the Canadian that helped make it possible?