While so many of the world’s wetlands have been drained to make way for development, the Hudson Bay Lowlands remain intact. And yet, it is a region and habitat that few Canadians know much about. I thought it was high time to bring the world’s third largest wetland (and second largest peatland) to our collective attention.

These wetlands are having a bit of a moment in our climate change-focused world for being critical carbon sinks. While that story is increasingly important, there are plenty of other fascinating tales to be told about this particular boggy territory, from glacial drama to ecological impacts, from contentious industrial development to a place more than 15,000 people call home.

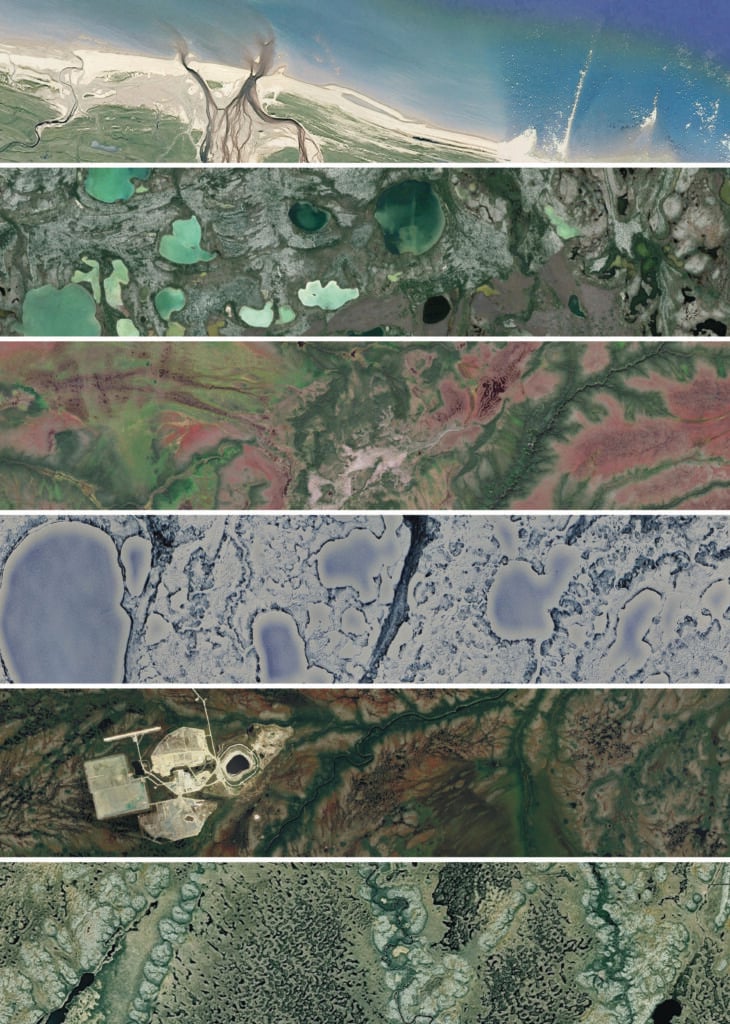

Landscape from space

Pattern, form, colour and texture are implicit joys in the craft of map-making. When I sit down to make a map, I never begin with a blank canvas; I start with the interconnected, ever-beautiful patterns of our planet. Though these satellite images are not maps (a map requires some level of categorization and symbolization), they speak to the diversity of form found in the Hudson Bay Lowlands. And while, from the ground, this massive expanse of flat land slowly draining towards the sea can appear less than dramatic, a cartographer is privileged to be able to share the crow’s perspective, opening readers’ eyes to the beauty of the view from above.