People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

People & Culture

Burnout is a growing concern for those in many industries, but many activists are seeing burnout as a new reality. In his book Taking a Break from Saving the World: An Activist’s Journey from Burnout to Balance, Stephen Legault looks at his journey in learning how to deal with burnout as an activist and find balance in his life.

Below is an excerpt:

To burn out you must once have been on fire.

—Unknown1

People who are deeply engaged in the good work of saving the world2 – regardless of how grand or humble our efforts – can at times suffer from an inability to remain resilient. In plain speak, we burn out.3

If we’re employed in the nonprofit sector, this can lead to serious problems that can impact our careers. We may feel compelled to quit, we may get fired when our work suffers, and we may suffer from physical or emotional health problems.

Despite increasing efforts by the organizations in the nonprofit sector, when staff burn out it can feel as if we are on our own. As the voluntary sector is often working right at the margins of its capacity to sustain itself, when one of our team suffers burnout, the result can be a transfer of the workload, and its accompanying anxiety, to other teammates.

The rate of suicide among people who identify as social-profit employees or volunteers has long been a point of concern. In a March 2018 New York Times piece, John Eligon investigated the high rate of premature death among founders and activists from the Black Lives Matter movement. “With each fallen comrade, activists are left to ponder their own mortality and whether the many pressures of the movement contributed to the shortened lives of their colleagues.”4

“I’m skilled at eluding the fetal crouch of despair – because I’ve been working on climate change for thirty years,” says author and activist Bill McKibbon in the New Yorker magazine. “I’ve learned to parcel out my angst, to keep my distress under control. But, in the past few months, I’ve more often found myself awake at night with true fear-for-your-kids anguish.”5

Long-term physical or mental health issues can and have sidelined some of the most promising activists striving for social change. This can have a lasting impact on their ability to live fulfilling, healthy and rewarding lives. Aside from the personal impact of these challenges, the impact of burnout and its outcomes can be challenging for the management of the organizations that are striving to make the world better. Loss of productive labour hours, high staff turnover, low morale and toxicity in the workplace all take their toll. The cost to recruit and train new staff, and the significant loss of institutional memory can be significant obstacles to the success of social-profit organizations.

“Non-profits tend to ‘run on tired,’” says Tracy Vanderneck, president of Phil-Com, a Florida-based consulting firm. “They may have too few staff members doing too many jobs and always feel like they are behind.”6 The personal crisis, and the crisis facing the nonprofit sector, is not likely to get any better. The new energy injected into the climate emergency through student-led strikes, the Green New Deal and the debate over climate change as a dominant issue in the politics of many countries worldwide has attracted a new generation of activists. Some, like those who identify themselves as the Sunrise Movement, are young, well educated and racially diverse.

If I could say one thing to the new generation of activists – from the Sunrise Movement to Black Lives Matter to Idle No More – it would be this: it’s a marathon, not a sprint. To survive such an endurance race as we face in the effort to address the climate emergency, inequality and the myriad crises of our generation, we have to pace ourselves. If we don’t, we run the risk of great personal challenges, and we won’t be around continuing the struggle we feel so passionately about now.

While our organizations have an important role to play in addressing burnout and its consequences, it’s at the personal level that each member of the global activist community can make a difference. Learning to stay healthy as an activist often runs

contrary to the self-sacrificing nature of those who are compelled to make the world a better place. I am advocating that sometimes we have to take a break from saving the world. Once in a while, regardless of how important our work is – and the role it plays in defining the story of our own lives – we have to eddy out. To “eddy out” is a phrase coined by canoeists, kayakers and other river runners. When you’re paddling a river – especially one with rapids and other obstacles – sometimes you need to take a break in order to rest, scout the way forward or just appreciate the majesty of moving water.

To take a break you have to look for an eddy – a spot on the inside bank of the river where a rock, or some other obstruction, creates a sheltered section of water where the current is calm or reverses direction and moves back upriver. Once in the eddy you can rest on quiet water as the river rushes by. This can provide a much needed rest on a big river, and gives you a chance to even step out of the boat to scout downstream for rapids, hazards and more good clean fun.

The real capital that fuels the nonprofit sector is passion. The people who make up the ranks of grassroots volunteers, staff and leaders of this sector have extraordinary potential to change the world. The sidelining of that potential due to burnout may be one critical factor that determines if we are ultimately successful in our efforts to make the world a better place.

Taking a Break from Saving the World is a short manifesto told from my own 30-year experience in the cause-related workforce. The book is intended to be both practical and inquisitive. I want you to come away with some ideas that you can apply in your work and life immediately, while giving you something to think about that helps frame our quest for greater purpose and meaning through good work.

The pressure of saving the world is at times overwhelming and can lead to breakdowns in people’s personal lives, their withdrawal from long-term participation in the voluntary sector and serious risks to their physical and mental health, including the risk of suicide. Facing overwhelming challenges such as climate change, natural disasters, famine, disease, poverty and the loss of biodiversity can at times feel crushing.

One of the side effects of the taxing nature of the work in the NGO sector is the need to eddy out. To step out, take a break and learn how to manage the pressure of saving the world. Typically, there are three ways this might happen: we can quit, we can burn out or we can get fired.

There is a fourth way we can respond to the pressure that arises from our efforts to make the world a better place: we can eddy out. We might come to understand the difficulty inherent in the work we do, and adjust both our proactive approach and response to it to avoid the pitfalls that lead to quitting, burning out or being fired. We can build in resilience tools and create the physical and emotional space needed to sustain ourselves in the stressful work of the voluntary sector in a way that allows us to gain perspective and then opt to get back on the river when we’re ready.

This manifesto is dedicated to three simple ideas. The first is to learn when and how to eddy out, regardless of our particular circumstances. The second is to explore what to do when we find ourselves in the comparatively quiet waters of an eddy. Finally, we’ll look at when, and how, to eddy back in.

At the end of each chapter of Taking a Break I’ll make a few notes on how to get the most out of that particular section of the book. I’m calling these “Notes on Technique” to fit with the theme of a paddling guide. Here are a few of things to consider:

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

Environment

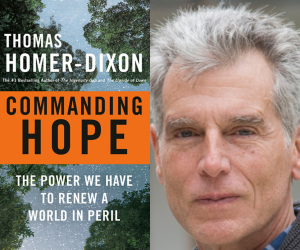

In an exclusive excperpt from his new book Commanding Hope, Thomas Homer-Dixon highlights four key stresses that inhibit society's collective sense of a promising future for our planet

Wildlife

How ‘maas ol, the spirit bear, connects us to the last glacial maximum of the Pacific Northwest

People & Culture

Indigenous knowledge allowed ecosystems to thrive for millennia — and now it’s finally being recognized as integral in solving the world’s biodiversity crisis. What part did it play in COP15?