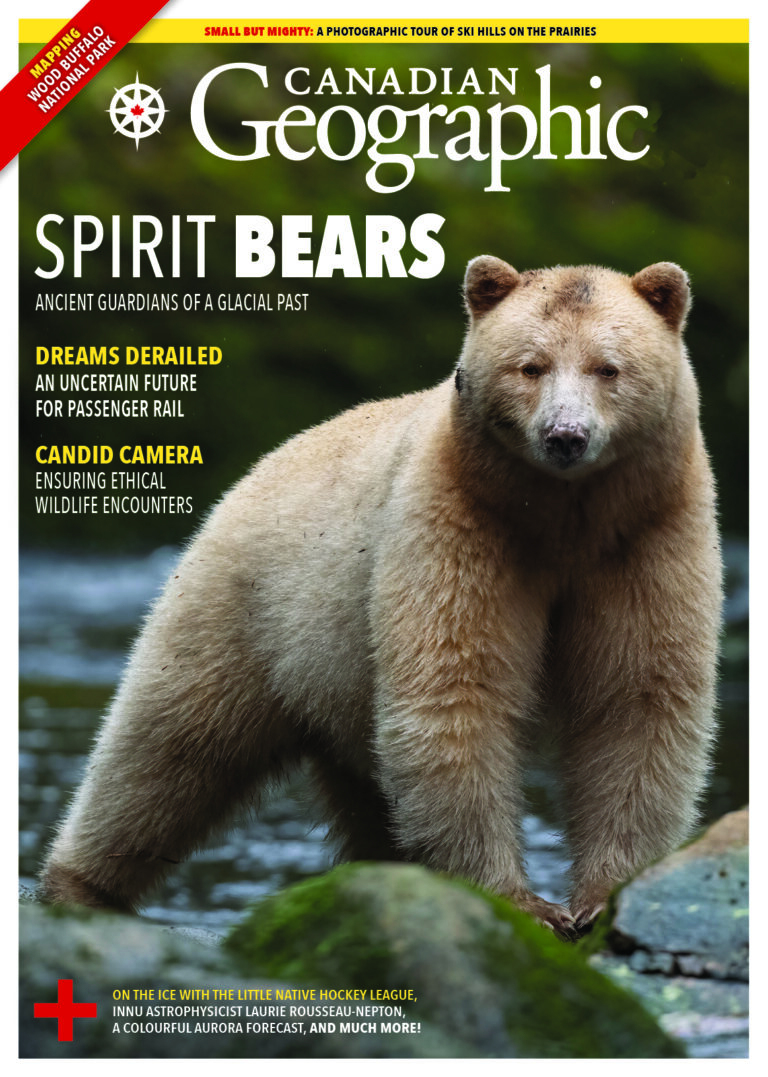

One of these youths is Troy Robinson, who has found reconnection while working at Spirit Bear Lodge. “Keeping the culture alive and moving forward generation after generation instead of being lost — even though it is a small part, the lodge still plays a big role in teaching the younger people the stories that hold the history and the morals,” he says.

While in Kitasoo Xai’xais, I saw people developing new stories to add to their adawak, or histories. A story key to their recent history is the development of the Spirit Bear Lodge. The Elders in the community were one of the driving forces behind accomplishing this goal. Doug Neasloss is the director of stewardship at Kitasoo Band and one of the leaders who helped turn the Spirit Bear Lodge into reality. He reflects on why the Elders made the tough choice to bring strangers into the community and how this decision may help preserve the nation’s culture and way of life.

“In tourism, people get paid to be themselves. They can go out there and interpret who they are and where they’re from,” says Neasloss. “We have watchmen programs, we have language programs, we have people doing a number of different science programs.”

“Seeing what the lodge does within the community and the pride that it brings to the people — it’s beautiful,” says Troy Robinson. “It’s a way for them to connect to their roots. I want people to come to my community to learn about the people, to learn about the culture — and getting to see the spirit bear is an extra.”

In the Big House, the wisdom Roxanne Robinson imparts is profound, touching not only on history but also on the future.

“When my daughter was months old, a spirit bear swam onto the island and was in the community,” she says. “My 99-year-old Nan came out of her house and walked with us to see the bear. She spoke our language and welcomed the bear as family. It showed how important all life is to our people. Getting to walk amongst and co-exist with the wildlife out there is so important. It is a part of our culture.”