“He did not, however, fall, but stopped and faced me, pawing the earth, bellowing and glaring savagely at me. The blood was streaming profusely from his mouth, and I thought he would soon drop. The position in which he stood was so fine that I could not resist the desire of making a sketch.”

And sketch Paul Kane did on that June day in 1846, several days ride south of present-day Winnipeg, with Métis hunters and thousands of bison thundering around him in a maelstrom of excitement and confusion — even though seconds later the bison he’d just shot would charge, prompting the artist to spring back onto his horse and make a narrow escape.

Being run down by one of the largest land mammals in North America would put a damper on anyone’s day, but it would have been particularly inauspicious for Kane, who was just seven weeks into the second leg of a nearly three-year cross-continental journey that would establish him as the pre-eminent visual chronicler of mid-19th-century Indigenous life and landscapes in Canada.

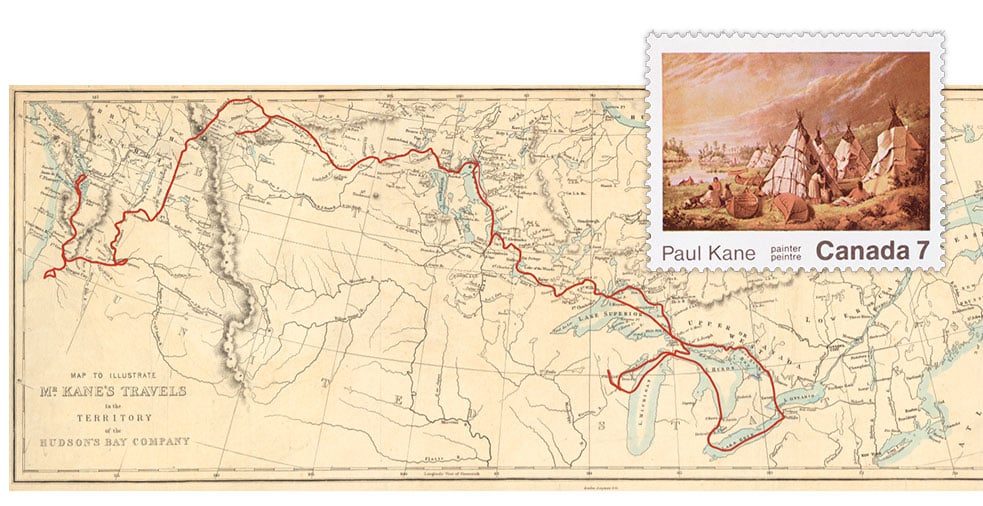

Kane’s 1845-1848 route is shown in red on the above map, which was included in Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America: From Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Territory and Back Again, his ghost-written travelogue, published in 1859. The book is peppered with other descriptions of wildlife encounters — a seemingly contemptuous grizzly bear here, ravenous wolves devouring drowned bison carcasses there — but as Kane notes in the book’s preface, his aim was to “sketch pictures of the principal chiefs, and their original costumes, to illustrate their manners and customs, and to represent the scenery of an almost unknown country.” And he delivered in spades.

During his travels — by foot, horse, canoe, boat and dogsled — Kane made more than 700 sketches, many of which he’d later use as the basis for a grand project: a cycle of 100 oil paintings documenting the people and landscapes he’d encountered, ranging from an encampment on the shores of Lake Huron (reproduced for a Canadian stamp issued in 1971, see inset above) to a portrait of the Plains Cree Chief Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow.

Today, Kane’s paintings are assessed more critically than they were in the mid-1800s — overly romanticized depictions that transformed Indigenous people into noble-savage stereotypes pretty much sums it up — but his contribution to recording the country’s original inhabitants, is still acknowledged to be matchless. “His work has no photographic parallel, for no one had yet turned a camera on the prairies and beyond,” writes Arlene Gehmacher in her book Paul Kane: Life & Work. “Kane thus built an enduring and valuable primary visual record of a culture that we otherwise would not have.”

*with files from Erika Reinhardt, archivist, Library and Archives Canada