Wildlife

The (re)naming of caribou

The failure to recognize distinct species and subspecies of caribou is hampering efforts to conserve them. So, I revised their taxonomy.

- 1540 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Wildlife

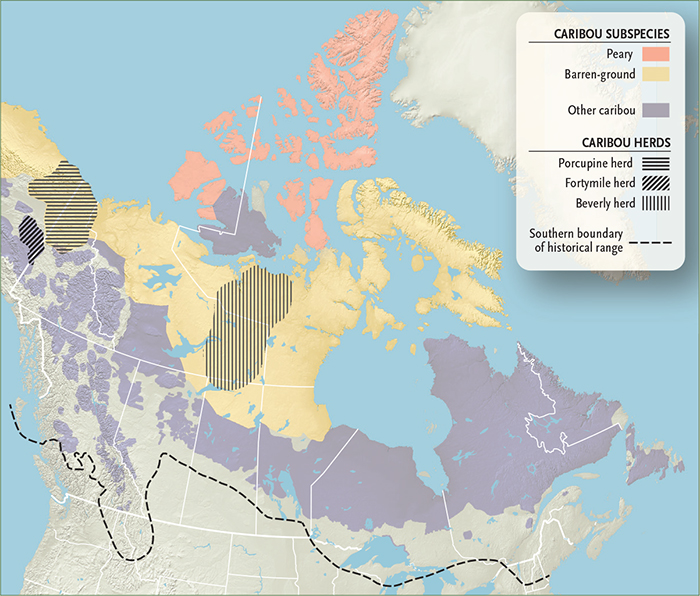

The Porcupine caribou herd, whose range extends from Yukon through Alaska, is known for its unfortunate choice of calving grounds: Alaska’s hydrocarbon-rich Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, where oil development could greatly affect the herd. In early June, nutritionally deprived females give birth to calves near the Beaufort Sea and spend a month foraging and feeding their newborn young in a relatively predator-free idyll. This is a critical stage in the caribou life cycle — the time when adult caribou are most sensitive to human disturbance and the likelihood of calf mortality is 50 per cent.

Scientists were shocked when a 2006 survey of the Beverly caribou herd, which ranges through Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Manitoba, Alberta and Saskatchewan, revealed it had virtually disappeared — down from a population of about 276,000 in 1994. Inuit in Baker Lake, Nunavut, however, knew better. “They said, ‘You got it wrong,’” says Mitch Campbell, the biologist for the territory’s Kivalliq region, “‘They’re not dying off, they’ve switched calving grounds.’” Sure enough, aerial surveys revealed that the herd had abandoned its traditional calving grounds for the first time in recorded history. Theories about the sudden shift abound, including harassment from aerial mining surveys and increasing wolf populations.

A 1920 estimate pegged the Yukon’s Fortymile herd at 568,000 — enough to force paddlewheelers to tie up while migrating caribou crossed the Yukon River. Increased hunting pressure due to the construction of northern highways, as well as more wolves and extreme weather, caused their numbers to drop to 6,000 by 1973. The herd subsequently concentrated in Alaska. Between 1997 and 2002, biologists ran a wolf sterilization program to aid the caribou recovery. The efforts paid off: in late 2002, some 30,000 caribou migrated back into the Yukon for the first time in 50 years.

The population of the Peary caribou subspecies, endemic to Canada’s High Arctic Archipelago, was estimated at 700 in 2009, down from 24,000 in 1961. The decline is attributed to “severe icing episodes” (when the vegetation caribou feed on gets encased in ice because of fluctuating temperatures, causing caribou to starve). The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada lists the Peary herd as “at imminent risk of extinction” due to climate change.

Migratory caribou have a narrow window to fuel up each spring, when Arctic plants yield the most protein. Caribou movements have adapted over time to coincide with “green-up,” says University of Alberta researcher Liv Vors. These strategies are thrown off, however, by the early arrival of spring — a regular occurrence in recent years. Similarly, Vors says warmer summer temperatures mean more biting and parasitic insects, which distract caribou from feeding. It all adds up to a shortage of nutrients and a lower survival rate for both adults and calves.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Wildlife

The failure to recognize distinct species and subspecies of caribou is hampering efforts to conserve them. So, I revised their taxonomy.

Wildlife

After more than a million years on Earth, the caribou is under threat of global extinction. The precipitous decline of the once mighty herds is a tragedy that is hard to watch — and even harder to reverse.

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

Wildlife

Caribou numbers in Canada are dropping drastically — and quickly — leaving the iconic land mammal on the brink of extinction