Science & Tech

20 Canadian innovations you should know about

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

- 3327 words

- 14 minutes

People & Culture

A century after the Group of Seven became famous for an idealized vision of Canadian nature, contemporary artists are incorporating environmental activism into work that highlights Canada’s disappearing landscapes

Saskatchewan artist Geoff Phillips mountain biked his way around the province’s southwest a few years ago looking for patches of wildflowers, native grasses and other plants he could paint in the body of work that would become Plantscapes of the Prairies. He soon learned he had to visit areas such as Grasslands National Park and Cypress Hills Interprovincial Park to find plentiful displays of native plants: “I realized you’re not going to find interesting plants and things growing that aren’t in protected areas.”

The 12 large paintings Phillips created serve as a stern warning: Many plants native to the prairies are disappearing as a result of the relentless sprawl of agriculture. Consider the western red lily, the provincial floral emblem on the Saskatchewan flag. The flower used to be plentiful but now is a protected species. It is no longer just a symbol for Saskatchewan, but also a symbol for disappearing nature.

Across the country, many of Canada’s top contemporary landscape artists are warning about the dangers to nature from agriculture, industrialization and climate change. “Artists, after all, are the canaries in the coalmine that point us to look at things that society is not grappling with the way it should be,” says Sarah Milroy, chief curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the art gallery based in Kleinburg, Ont., that’s famous for its massive Group of Seven collection.

A century ago, Canada’s top artists were the emerging Group of Seven. They painted what were presented as newly discovered landscapes, unspoiled and uninhabited, although Indigenous peoples had lived in those areas for thousands of years. Today, the country’s artists are painting not newly discovered landscapes but instead the increasingly threatened landscapes of Canada.

The Group’s wilderness paintings have long been the gold standard of landscape art and remain so for many Canadians. But that standard is changing as artists forge a new path, using their art to galvanize contemporary viewers to act to protect the landscapes that so inspired the Group of Seven.

The Group can, perhaps inadvertently, take some of the blame for the threatened destruction of nature. These days, their paintings are critiqued as invitations to mining, logging and tourist companies to occupy the wilderness. “Lots of the Group of Seven paintings were portraits of our natural resources to exploit,” says Lindsey Sharman, a curator at the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton.

—Sarah Milroy, chief curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection‘Artists, after all, are the canaries in the coalmine that point us to look at things that society is not grappling with the way it should be.’

The Group of Seven formed amid the surge in Canadian nationalism following the First World War. “The National Gallery and the Group of Seven shared common goals — to further an awareness of art and of the importance of Canadian art for the development of Canada as a nation,” wrote Charles Hill, former curator of Canadian art at the National Gallery of Canada, in his 1995 exhibition and book, both titled The Group of Seven: Art for a Nation. And no Canadian art was championed more by the National Gallery than the Group of Seven.

The gallery’s admiration for the Group was not matched by the critics and collectors during the early days of the seven artists. But the Group persevered, eventually reigning over the domestic art world. The Group’s hold on Canada was boosted during the Second World War when the federal government and National Gallery, in a drive to boost patriotism, started a project that lasted for two decades, sending silkscreen prints of Group paintings to public buildings and schools across the country. The message: Good Canadians love the Group of Seven.

The Group of Seven’s Lawren Harris and Arthur Lismer believed the Canadian “environment” moulded the “Canadian character and thus Canadian art,” Hill wrote in Art for a Nation. Today, a very different interpretation of that word “environment” is moulding Canadian art — and nationalism and patriotism are no longer at the heart of this movement. Acceptance of the need for environmental protection is gaining ground, and artists help lead us. This magazine chose five contemporary landscape artists to profile alongside this story, their works motivated by their reverence for Canadian landscapes under threat.

Espanola, Ont.

Art is one of the weapons of this Métis eco-warrior and Indigenous rights activist living in Espanola, Ont., just north of Manitoulin Island. “Every good revolution has revolutionary art,” she is wont to say.

This desire to sustain nature in all its forms and “my love for the earth drive my life and my art,” she wrote in a book, simply titled Christi Belcourt and released in conjunction with a nationally touring retrospective of her work during 2018-2020.

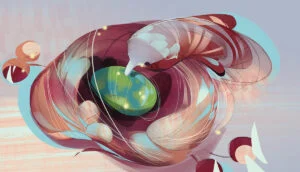

Belcourt is best known for her magical, constructed landscapes showing the harmonious intertwining of plants, birds and insects in the ecosystem. The scenes are created from thousands of tiny drops of paint applied to canvas, often using a knitting needle. Each painting resembles iconic Métis beadwork.

Belcourt’s art is collected by major Canadian art museums and various Indigenous institutions across the country. Consider The Wisdom of the Universe, a painting almost two by three metres commissioned by the Art Gallery of Ontario. Nature comes alive as if in a movie. You can almost see the leaves of plants swaying in the breeze, the birds and insects coexisting in this idyllic setting. The reality: Wisdom incorporates more than 200 species of Ontario plants and animals that are listed as threatened, endangered or extinct.

This is the kind of scene Belcourt wants Canadians to appreciate and protect. “We have the power to remake the kind of world, the kind of future, we want,” she has said.

Belcourt believes stolen lands must be returned to the care of Indigenous people for safekeeping. As she told a conference at Laurentian University in Sudbury in November 2016: “Canada represents the largest land heist, the largest land theft, in the history of the world.”

Maple Creek, Sask.

One of the most famous works from the Group of Seven was painted in 1916, four years before the artists officially joined forces. It is not one of the wilderness scenes for which the Group is best known. Instead, it is The Tangled Garden by J.E.H. MacDonald, depicting an overgrown Art Nouveau-style flower garden at the artist’s home north of Toronto.

“It’s one of my favourites,” says Geoff Phillips, a truth that is evident upon viewing Phillips’s body of work created in 2017 called Plantscapes of the Prairies. The 12 oil paintings, each about 4.5 by 5.5 feet, depict fields of grasses, wildflowers and other native plants echoing the style of The Tangled Garden.

Phillips had to travel to protected areas such as Grasslands National Park to find such a cornucopia of flora because many native prairie plants have almost disappeared amid the widespread cultivation of farmland.

To find the perfect spot to paint, Phillips rode his mountain bike along rough terrain, then spread his canvas on the ground, outlined a rough draft in brown acrylic paint, then headed home to finish the work. This is a similar process to the creation of many Group paintings.

The Group, along with Indigenous artists such as Bill Reid and Norval Morrisseau, have been Phillips’s strongest influences, he says.

Plantscapes was first shown at the Art Gallery of Swift Current in 2017 and in 2019 embarked on a planned tour of 17 other art galleries in Saskatchewan. The tour continues into 2022. From his grave, J.E.H. MacDonald must be envious. The Tangled Garden was widely pilloried when first exhibited more than a century ago. Saskatchewan heartily embraced Plantscapes of the Prairies from the beginning.

Edmonton, Alta.

When Dwayne Martineau was a child, his father gave him a Kodak Instamatic. Before taking one photograph, young Dwayne taped a piece of red plastic over the lens. No ordinary pictures for this boy, a member of the Frog Lake First Nation in northern Alberta.

Decades later, the lens work from this Edmonton-based landscape artist remains focused on the extraordinary, in all senses of the word. Consider his short video Shallow Forest, which is dominated by a central conical structure resembling a Byzantine pillar. Twirling tree branches circle around it. A primordial soundscape created from the distorted rumble of a flowing creek adds a menacing tone. The pillar, by the way, is a pile of leaves transformed by mirrors and other photographic trickery into a giant kaleidoscopic image.

Martineau’s investigation of our emotional connection to nature is often presented through the eyes of a tree or, as the artist terms it, a “great powerful monster.” Some of the photographs and videos of trees are downright frightening, especially when arranged in a circle, as was done at the 2021 exhibition Strange Jury, at the Art Gallery of Alberta in Edmonton. The trees seemed to be passing judgment on the visitors entering the circle.

There are no sweeping vistas in Martineau’s work. He is more interested in investigating a clump of moss or the underside of a leaf. Think of the insect life teeming in a patch of grass, he says. You can find there death, beauty and cruelty. “The most intense story happening on the planet might be in your backyard right now.”

Toronto, Ont.

Viewing Edward Burtynsky’s landscape photographs is a guilty pleasure. We are enchanted with the colours, composition and otherworldliness but are simultaneously repelled by the content — polluted rivers turned radioactive orange, bald mountains denuded of forests and the apocalyptic symmetry of endless acres of oilwells.

“Burtynsky’s photographs may show us things that are disturbing but they also have about them an unexpected beauty, subverting our usual notions of the sublime in nature and leading us to a new awareness of the landscape of our times,” wrote curator Lori Pauli in the catalogue for Manufactured Landscapes, a National Gallery of Canada exhibition in 2003.

Burtynsky shoots the most scarred and abused landscapes on the planet, some of them in Canada. Pauli describes Burtynsky’s work as “not overtly political.” Really? Burtynsky does not preach, condemn or offer solutions to the Earth’s problems. But he does want solutions.

In 2018, Burtynsky, along with filmmakers Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, unveiled Anthropocene — a multimedia artwork that included an exhibition, a book and a movie, all of the same name, detailing scenes of massive environmental destruction and plunder around the world.

These are landscapes of terrible beauty, presented with panache and daring. “We feel that by describing the problem vividly, by being revelatory and not accusatory, we can help spur a broader conversation about viable solutions,” Burtynsky wrote in Anthropocene, the book.

Wakefield, Que.

Gavin Lynch considers the canvas on his easel to be a “stage.” He is the set director acquiring props from both the physical and virtual world to create a picture that is an ongoing dialogue between traditional painting and screen culture. A walk in the forest surrounding his home near Wakefield in west Quebec’s Gatineau Hills sparks inspiration for his surreal landscapes. So, too, do images from photographs, historical art and the internet. All are used to create digital landscapes that he then “reinterprets” in paint on canvas. The result is iconic Canadian landscapes for the digital age, the Group of Seven electrified.

The paintings of stylized forests may look eerily theatrical, with tree trunks impossibly straight and the lighting surprisingly intense. But this son of the British Columbia logging town of Burns Lake definitely wants you to view his canvases as earthly. He wants you to think of the natural environment we have now and what could soon be destroyed by climate change.

“These are the spaces that are worth protecting, even if they are idealized or transformed through the act of paint- ing,” Lynch said in an interview at the end of 2021, a year his native British Columbia was ravaged by heatwaves, forest fires and floods. “Landscape painting has really never been more important than it is now. It’s a reminder of what is at stake.”

Early in Lynch’s career, a decade ago, he created scenes of floods and fires and storms in some of his surreal forests. “When I first started, they were posited as ‘what-ifs.’ They’re not ‘what-ifs’ anymore.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the July/August 2022 Issue

Science & Tech

Celebrating Canadian Innovation Week 2023 by spotlighting the people and organizations designing a better future

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?