Travel

Trans Canada Trail celebrates 30 years of connecting Canadians

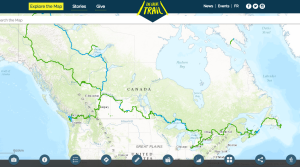

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

- 1730 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

The Canol Trail has been called one of Canada’s hardest trails. It’s remote, unforgiving and has a healthy population of grizzly bears But long before claiming a place on every iron-toed hardcore backpacker’s bucket list, the Canol began as something much different and, for a time in the 1980s, almost didn’t exist at all.

“The Canol Road was a road built by the United States Army during the Second World War to service an 800-kilometre pipeline linking oil fields at Norman Wells, NWT, to a refinery at Whitehorse,” Lyn Hancock writes in her March 1982 article titled ‘Canol Road dilemma: Is easy access spoiling Yukon’s old pipeline route?’

After only 11 months of operation, the war ended, and, with Pacific shipping routes once again safe, there was no further need for the Canol (which stands for Canadian oil). Whitehorse’s refinery was shut down, dismantled and shipped south. Normal Wells reverted to local oil production.

Like Second World War U.S. Army projects all over the North, it was often cheaper to just leave everything in place than pack it up and cart it home. By the 1980s, the huts, fencing, barrels, kilometres of telephone cables and vehicles the army had abandoned had either been scavenged by locals or repurposed for tourism. Apart from a few outposts, the 800-kilometre scar of the Canol was slowly being reabsorbed.

“Where once thousands of construction workers cursed the muskeg, mosquitoes and their frontier existence, today hikers, canoeists, hunters and naturalists rejoice in its grand and sculpted landscapes, its rushing rivers, its abundant wildlife, and its summer flowers,” Hancock writes.

“Yet, as the world first came to know the Canol through oil, now it is learning about it through copper and tungsten, silver, lead and zinc.”

Yukon officials had resurrected the 465-kilometre stretch of the Canol Road on their side of the border as a means to access mines. And, though the Northwest Territories portion of the Canol was designated a hiking trail when Hancock visited, the local government was exploring mining options there too.

From her base at Oldsquaw Lodge (now called Dechenla Lodge and Wilderness Resort), Hancock witnessed myriad possible futures for the Canol (including a disturbing passage about “road hunters” shooting a caribou calf from the comfort of their 4X4s).

“The hunter, the naturalist, the miner, the tourist, the hiker, the scientist, the businessman — all have varying values and all impose their pressures on the revived Canol Road,” Hancock writes. “At the moment the Canol in the NWT is designated as a hiking trail. Some want it upgraded for mining and tourism; some want it kept as a heritage hiking trail; others want it to remain a forgotten road, left to the wild and its wildlife.”

Thirty-four years later, the hikers have won. The Canol Heritage Park Trail was designated a National Historic Site in 1990 and now plans are underway to make it part of the proposed Doi T’oh Territorial Park. It’s a move that would all but guarantee it remains as it is: a beacon for extreme hikers and a link to a time when Canada’s North was home to a little-known part of the Second World War theatre.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

The trail started with a vision to link Canada coast to coast to coast. Now fully connected, it’s charting an ambitious course for the future.

Mapping

As Canada's most famous trail celebrates its near completion, Esri Canada president Alex Miller discusses the ambitious trail map that is helping Canadians get outdoors

Travel

An ancient Mi’gmaq migration route that follows the Nepisiguit River’s winding route to the salt waters of Chaleur Bay, the Nepisiguit Mi’gmaq Trail is now one of the world’s best adventure trails

Travel

Inspired by age-old travelways, a new canoe route knits together the Trans Canada Trail