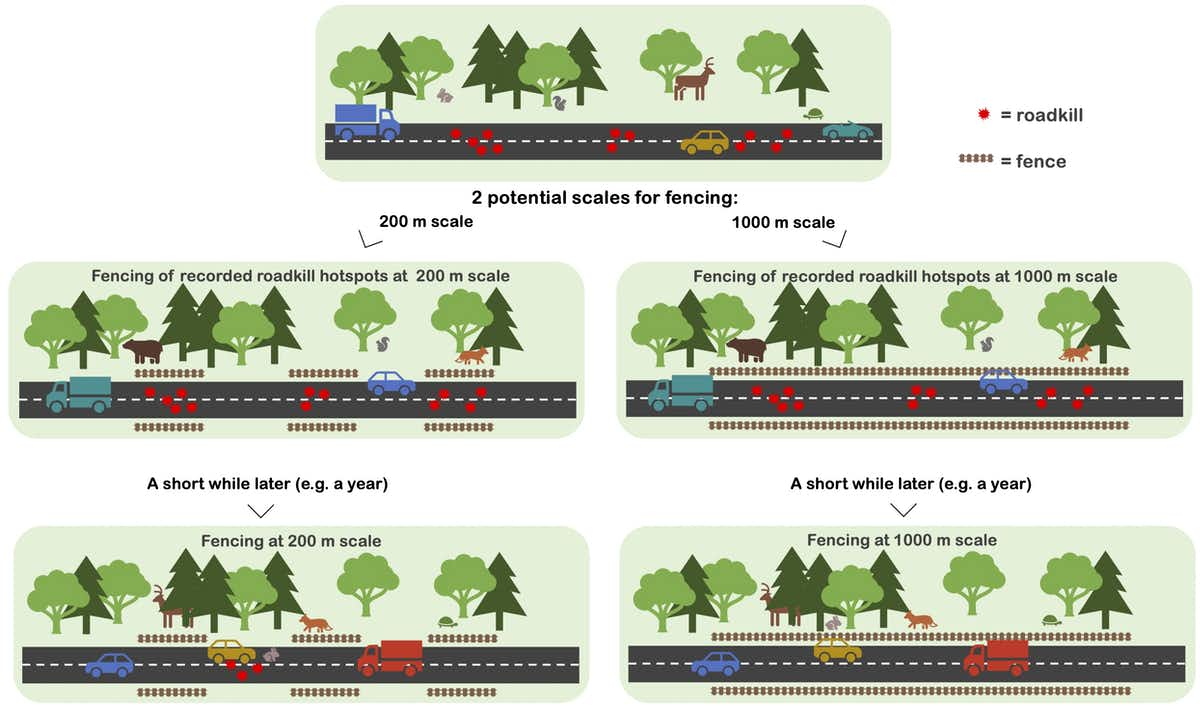

Are your fences too short? Transport agencies may decide to fence the three hot spots identified at the 200-metre scale (left) or the one hot spot identified at the 1,000-metre scale (right) to reduce roadkill, but the longer fence from the analysis at the 1,000-metre scale clearly does a better job in this example. (Authors), Author provided

Roadkill hot spots can be identified at different scales, which can influence decisions about where fences should be placed. A hot spot at one scale may not be a hot spot at another scale.

We used roadkill data from three roads, one from southern Québec and two from Rio Grande do Sul, in Brazil. The first road cuts through the Laurentides Wildlife Reserve and borders the Jacques-Cartier National Park in Québec. One of the roads in Brazil crosses through two protected areas and runs along the Atlantic Forest Biosphere Reserve, while the other borders slopes of the Serra Geral Mountains and coastal lagoons.

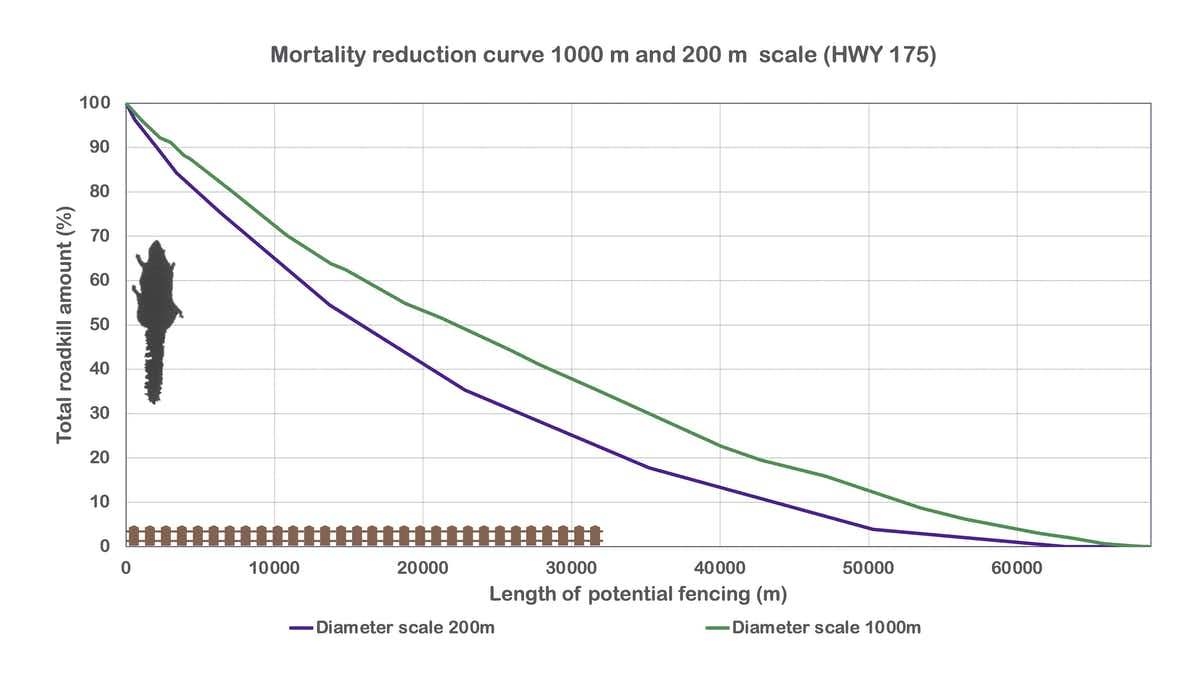

Initially, we thought many sections of short fences could be built near hot spots identified at a fine scale to reduce roadkill. We expected that this approach might also require less total fence length than fencing fewer hot spots identified at courser scales while achieving the same roadkill reduction.

However, animals can move easily around fences that are too short. They may then get killed at the fence ends — an issue known as the “fence-end effect.” The fences need to be long enough to reduce the danger of a fence-end effect.

A few long fences or many short ones?

This trade-off between the use of a few long or many short fences has important implications for biodiversity conservation. Finding the right balance depends on the distances that animals move, their behaviour at the fence, the mortality reduction targets for each species considered and the structure of the landscape near the road.

For example, turtles move across much shorter distances than lynx, and their roadkill hot spots are very localized. Accordingly, many short fences are appropriate for turtles, whereas fences designed for lynx need to be much longer.