Environment

Eight facts about water in Canada

How much do you know about Canada’s water — where it comes from and how it’s used?

- 727 words

- 3 minutes

Exploration

If you read or listened to the news in October about the discovery of “water” on the Moon, you might be wondering what all the fuss is about. Before we get into these latest discoveries, let’s clarify a few things.

First, if you look up the definition of water in most dictionaries it will state that this is the name given to the liquid state of H2O — this is not what was found on the Moon. Rather, scientists have discovered further evidence for frozen H2O, or water ice, and what we term molecular water, which is locked up in lunar materials — we’ll return to this later.

Second, a bit of history. Unlike Mars, where we see abundant evidence for the presence of past water (e.g., valley networks), and water ice locked up in the polar ice caps at the present-day, the general view of the Moon is that it has always been, and remains, virtually bone dry. Indeed, this was the view based on the initial studies of samples collected by the Apollo astronauts in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and also by the simple fact that H2O, in any form, will rapidly break down when exposed to sunlight on the lunar surface. During the remainder of the 20th century, a series of studies using data from spacecraft sent to the Moon, Earth-based observatories, and theoretical calculations, suggested that water ice might be present, but the studies were often contradictory or inconclusive.

Our understanding of water on the Moon has, however, changed dramatically during the first two decades of the 21st century. It had actually been theorized in the early 1960s, but a series of missions and other scientific studies have confirmed that there are places on the Moon that essentially never see the Sun — mostly in meteorite impact craters, which formed steep-sided depressions, close to the lunar poles. These are referred to as permanently shadowed regions or cold traps, and the temperatures in these areas have been measured to be as low as minus 238 oC! The idea is that any water, however miniscule in abundance, would be trapped in these cold traps and slowly accumulate over billions of years. This theory received a significant boost in 2008 and 2009 when India’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft NASA’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), respectively, conducted impact experiments on the Moon (essentially deliberately targeting a small mass at the lunar surface) and then analysed the plume of debris that was excavated. Both experiments detected water lending strong support for the presence of water ice in these PSRs.

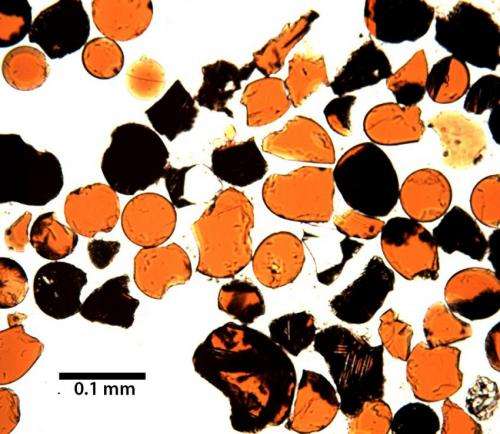

Another important piece of evidence came in 2011 when scientists re-analysed the famous “orange soil” collected during the Apollo mission in 1972. Using modern laboratory techniques not available in the 1970s, these scientists showed that these glasses, produced by volcanoes on the Moon more than three billion years ago, contained a substantial amount of water locked up in their structure.

Enter the latest studies. On the last Monday in October, two papers were published in the prestigious journal Nature Astronomy. In the first paper, scientists used data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft and showed that small cold traps down to one centimetre in diameter are present across the surface of the Moon — the previous studies mentioned above focused on large cold traps within huge kilometre-size craters close to the south and north poles of the Moon. They concluded that these small cold traps are the most abundant on the Moon and that they could account for approximately 10 to 20 per cent of the total area on the Moon. This may not sound like much, but this is roughly 40,000 square kilometres — which is about the area of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie combined, or a bit smaller than Nova Scotia!

The second paper was perhaps the most surprising. This study used data collected on NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) aircraft, a modified Boeing 747. This study discovered H2O in a meteorite impact crater called Clavius, not within a cold trap, but rather on the sunlit surface. Because H2O is not stable on the lunar surface, these scientists interpreted this data as representing H2O trapped within glasses that formed due to the intense temperatures and pressures generated during meteorite impact. No mission has ever landed in Clavius crater so whether these glasses resemble the orange glasses collected by the Apollo 17 mission remains to be seen.

Orange Soil at Shorty Crater. (Credit: NASA-Apollo 17 Crew)

So why is all of this important? What’s the big deal about water on the Moon? Well, this is not a search for life story: the surface of the Moon is just too inhospitable for life to have ever arisen. Instead, the presence of water ice on the Moon is hugely important to enable the long-term sustainable exploration of not just the Moon, but the solar system at large. The bottom line of space travel is that it is hugely expensive to launch anything from the surface of the Earth as you have to provide enough energy to escape Earth’s gravity. If we think about what types of materials we need to launch to enable human missions to the Moon and Mars, two of the heaviest things are water for humans to consume and for growing food, and rocket fuel. NASA’s rocket fuel of choice is hydrogen and SpaceX is developing methane/liquid oxygen engines for Mars, which requires a source of hydrogen and oxygen. Humans also of course need oxygen to breathe!

Put simply, if we can extract water from the Moon, it means we have to bring less with us from Earth, which both dramatically reduces the costs, and reduces the risks, of space exploration. This can only be a good thing.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

How much do you know about Canada’s water — where it comes from and how it’s used?

People & Culture

How a journey through the Great Lakes helped reshape my relationship with water after the loss of my father

Environment

Many of Canada’s 25 watersheds are under threat from pollution, habitat degradation, water overuse and invasive species

Environment

We use it every day, yet many Canadians don't know where the water that flows through their home comes from.That's according to the recently released