Environment

Space invasion: Is it too late to save the Great Lakes?

How a cocktail of invasive species and global change is altering the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River ecosystem

- 2231 words

- 9 minutes

People & Culture

How a journey through the Great Lakes helped reshape my relationship with water after the loss of my father

Shortly after my 25th birthday, in March 2017, my father passed away in a snowmachine accident. I remember the call clear as day. His snowmachine broke through the ice, and they couldn’t get him out in time. I went home immediately.

My life was irrevocably shaken. Not only had I lost my father, but water, something with which I have always had a deep spiritual connection, was the culprit. Two of the most important relationships in my life were forever changed.

I was always a mover, something I inherited from my Métis ancestors. I was able to make home in many places — the Dominican Republic, Uganda and Cuba, to name a few. I spent my time off from school on ranches in Alberta or biking across Canada. Even though I was always out gallivanting, as my mother would say, I maintained a strong sense of where I would end up. I often joked about moving back to the Soo (a.k.a. Sault Ste. Marie) area to become a hermit or medicine woman in a cabin on a lake, spending my days canoeing and harvesting wild teas.

If you’ve ever heard a sea shanty, if you’ve ever stood in awe of the vastness of the ocean, if you’ve ever laughed as waves splash upon you, you know that humans and water have a deep relationship. We are 60 per cent water after all. My relationship with water is a special one, being a Métis woman, raised on the shores of Bawaating (St. Mary’s River), which connects Lake Huron and Gichi Gami (the local name for Lake Superior, meaning “Great Sea” in Anishinaabemowin). My Anishinaabe and Métis ancestors travelled and lived on these waterways for generations. My Anishinaabe and Métis grandmothers would have been water protectors in their communities. Both the Métis and Settler sides of my family raised me on fishing, swimming, canoeing and just being on the land in general. And for you astrology lovers out there, I am a Pisces through and through.

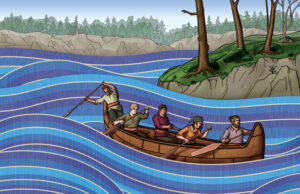

I knew when my father passed that I couldn’t also lose my relationship with water. Water has always given me a sense of place, belonging, calm and power. So, one month after his death, I took on one of the greatest physical and emotional challenges of my life. I hopped in a Montreal canoe with 17 other Métis youth, and for three and a half months, we paddled the historic routes of our ancestors, from Ottawa (Kichi Sibi) to Kenora (Wazhashk-Onigamiing), Ontario.

My story of that summer is one of grief, yes, but also one of relationship, responsibility and healing. Ultimately, it is a story of reciprocity, a value that is deeply held by Indigenous Peoples. As one Mā’ohi proverb so succinctly says, “The life of the land is the life of the people.” As I journeyed across the rivers and Great Lakes, I learned about my people and our connection to the waters, and about healing through the power of the water. I also gained a new sense of purpose — one that puts water at the centre.

The journey began in Ottawa. We paddled a 16-person, 35-foot fibreglass canoe fashioned in the image of the birchbark canoe, painted to detail the birchbark, the cedar gunnels and the pitch used to seal together the traditional vessel that our ancestors would have paddled. Weighing a colossal 270 kilograms, these finely designed vehicles were once the key to the economy, delivering heavy freight all across the Great Lakes and inland lakes and rivers. With one person acting as the rudder in the back and one person setting the pace in the front, the rest of us smushed into the canoe, two by two, and onward we went.

We followed the Kichi Sibi almost 300 kilometres to the Mattawa River, then continued onward 200 kilometres through Nbissiing (Lake Nipissing) into Wemitigoj-Sibi (the French River). From there we were on the Great Lakes. We sailed our way across 250 kilometres of Huron’s northern shoreline with a makeshift carved mast and a tarp for a sail. We had many hiccups along the way, but once we travelled through the Bawaating area, 200 kilometres from Biniwaabikong (Blind River) to Obatchiwanang (Batchewana), and made it to Superior, we really hit our groove. After Gichi Gami, we continued onward, up through the Gojijiwininiwag (Rainy River area) and into Pikwedina Sagainan (Lake of the Woods). We ended our journey with a grand welcome and big celebration at the Métis Nation of Ontario’s Annual General Assembly in Wazhashk-Onigamiing.

We were on the water day in and day out, paddling and portaging, sleeping at the beaches and river mouths where my ancestors undoubtedly camped, taking moments for prayer and ceremony at sacred sites and luxuriating in moments of pause, play and reprieve when the waters allowed.

The water dictated how our day would go. If it was a calm day, we took the time to rest, finding the nicest rock or beach to enjoy lunch and a swim — paddling extra hard to achieve most of the travelling distance in the morning so we could soak in the water, sun and company for the rest of the day. These were the days we would play games or sing songs as a crew, all the while paddling merrily on our journey.

On windy days, especially when we were far from our next touchpoint with our road crew (and cellphone service), things were more serious. We were often silent, each of us lost in our own thoughts — whatever enabled us to paddle that next stroke. For me, it was a meditation. In those moments, I didn’t have to think about my grief — I was completely entranced by the water. With each stroke, a breath. With each wave crashing against the canoe, a call to remain present. It was in those moments that I was able to exist outside of a world of grief. Each kilometre further removed, I was reminded that I was strong, that I come from resilient people and that I would continue to move forward.

Moving through the waterways became a metaphor for the grief moving through my body. In the rivers leading to Lake Huron, we ran across many barriers, some akin to those of our ancestors — small creeks and marshlands through which we had to portage. Others were more modern. We couldn’t sleep on the shores of Kichi Sibi as our ancestors had done because so much of the land is now privatized. We paddled from boat launch to boat launch, taking the giant canoe in and out of the water and hauling it and ourselves to the nearest campground. At this point, at the start of our journey, I was coming up against emotional barriers, too—I would dam up my own feelings of grief and sadness, and they would come out in powerful outbursts, just like the river rapids.

Lake Huron provided a much-needed reprieve from portaging, campgrounds and black flies. The days were warm, with calm, mirror-like waters. We received lots of kindness, generosity and delicious food from Métis communities and First Nations along the way. We sailed leisurely into Biniwaabikong, cutting out two days’ worth of paddling. I was grateful to be greeted by people from my own community, especially my sister and mom. I was greeted again by more family, my aunts and my grandmother, when we arrived in the Soo.

I saw a lot of family on our route. One of the other paddlers, whose Métis roots come from the Prairies, noticed I usually had at least one family member at every community event along the paddle. This was a time for me to acknowledge what had happened, to sit with the feelings of grief and sadness and to be loved and supported by those close to me, including the familiar waters of Huron’s north shore, where I was raised. I considered ending my journey here, to be around loved ones, but something urged me onward. I told myself that if I wasn’t happy by Animikii-ziibiing (Thunder Bay), I would stop there.

Once we reached Superior, we canoed in the morning while the waters were calm, then took in the lake’s charm after we set up camp in the afternoon. This meant exploring its many beaches, some of fine-grained sand or small effervescent stones, and others of large rocks like dinosaur eggs, rounded by the throes of the great Superior’s epic waves. There were lighthouses, sacred sites, saunas on islands peppering the coast and magnificent waterfalls, all gems tucked away for those confident enough to navigate the lake that “never gives up her dead.”

The journey of healing has

taught me a great many things,

many of which have to do with water.

We spent days — sometimes a week at a time — without connection to the outside world. There was no cell phone service, and certainly no proximity to the road crew to bring us ice cream after a hard day’s paddle. Among many days of wonder and adventure, there were also days where we had to paddle harder than we knew we were capable — days with waves so high that I had to bail the water out of the canoe as the others continued to paddle. Even in July, we had chilly days when all our clothes and gear were damp, when the winds howled, when we were down to the scraps of our food and when fellow canoers got seasick and had to lie in the bottom of the canoe as we trudged onward in wavy waters.

Something about this challenging time on Superior allowed me to reconnect with feelings other than grief. I have always felt a deep affinity to the lake, but being able to live my life in rhythm with its movements was life-giving. I felt awoken by, not fearful of, the lake’s frigid waters. I felt deeply relaxed while sleeping to the lulls of the waves. I felt powerful and enthralled as I paddled against the whitecaps. I felt joy in connecting with the many sailors, artists, adventurers, Knowledge Keepers, scientists and storytellers along our travels. It was a time of great healing. I was able to finish the rest of the trip to Kenora, not without struggle, but certainly with much more room in my heart for the gifts of life.

It has been six years since my father passed. I now live in a beautiful cabin on Gichi Gami. Every day, I look out at the lake and am empowered and healed. I see the life she gives to me, to the family of otters that catch fish off the shoreline, to the mother and adolescent eagle that fly over my house, to the great pine tree outside my window that defies gravity and to a great many others. I do not own this land or this waterfront. I am only here for a short time, and the rocks and waters will continue to be, long after I am gone. With the time that I do have, I seek to honour my relationship with the Great Lake that gives my life so much greatness. I am bound and determined to find a way to protect and heal this lake as she did me. This is reciprocity, this is relationship, and this is love. The time to act is now.

I sit writing this on a warm, early September day. My dog Thor, who I lovingly call Myeengun-onse (Little Wolf in Anishinaabemowin), and cat, Shadow, who I like to call Bishiw-onse (Little Panther), soak in the last days of sun on the deck next to me. The lull of the waves and the cool breeze have us all relaxed. It is a relatively rare day for September. The winds usually start picking up around this time, leading up to the infamous gales of November on Lake Superior. On days like these, I am reminded that all beings need rest, even the Greatest of Lakes.

Each day, the lake gives me something to be grateful for. It gifts me with lessons and love. In moments where I feel heavy, the northern winds remind me of lightness and the importance of breathing. In moments where I feel alone, the rising sun warms my back like the caress of a loved one. When I am feeling angry, the lake responds with thrashing waves, reminding me that it is okay to be furious. If I am anxious, the glassy morning waters call me to tap into my inner calm. What the lake continually teaches me is to not fight my own nature.

My connection to water is part of my own nature. It is something that I have inherited from my ancestors. It flows through my veins just as the rivers and streams are the lifeblood of Shkaakaamikwe (Mother Earth). The closer I get to the lake and my own nature, the more I understand that our well-being is tied to one another.

My water comes from the lake. I draw it into my house, to a pool in my basement. It is a gift to be drinking the waters from Gichi Gami. As a good friend told me, if I am 60 per cent water, and the water I am drinking is from Gichi Gami, then 60 per cent of me is Gichi Gami. If the lake is well, I am well. If the lake is sick, I am also sick.

My first year moving home, I was excited to go smelt fishing, one of my favourite springtime activities, taught to me by my father. Smelts are a small, silvery fish that travel in large schools up rivers and streams in the early springtime. At night, with flashlights, friends and family, we head to tucked-away creeks and river mouths to catch dozens of these small fish in special handheld nets. They are delicious fried and crispy golden, and any leftovers from gutting the smelts go to the compost to bring the rich nutrients from the water onto the land, into the plants and, eventually, back into the bellies of myself and my family.

And yet, that same year, the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources issued a warning to locals to minimize smelt consumption, due to the presence of “forever chemicals,” or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Known as PFAS chemicals, they are associated with reduced fertility, thyroid disease and liver damage. This especially applied to smelts coming from Gichi Gami. If forever chemicals are found in fish at the lowest end of the food chain, what does it mean for those who eat those fish— larger fish, otters, birds, bears, humans? “The life of the land is the life of the people,” right?

The state of the water’s wellness, and thus our own wellness, is under daily threat. In Canada, where we have of the highest quantities of freshwater “resources,” water is extracted from underground aquifers by corporations like Nestlé and by other industry giants using exorbitant quantities of fresh water for processing with little care given to the state of the water when it re-enters the ecosystem.

But we, as humans, created the threat, which means we can also create the solution. Indigenous Peoples are often at the forefront of climate change solutions because of our unique and grounded relationship to the lands and waters. We are acutely aware of the patterns of the lands, waters and animals because our own living patterns often model these seasonal shifts. Because of our intimate relationship with the land, we are also the most vulnerable to climate change, pollution and environmental degradation. Yet we continue to steward these lands, with place-based, specific knowledge passed down from generation to generation. In maintaining our connection to the land, waters and ice, we continually reaffirm our responsibility to care for that which gives so abundantly to us.

I want the people of this world to know that they, too, can and do have a relationship with water and that their very existence, and that of their grandchildren, depends on honoring that relationship. I want people to know the Great Lakes.. more deeply — the sickness of Lake Ontario, the serenity of Lake Huron and the power of Lake Superior. I want people to care.

I finish writing this article on September 29, the day before the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. A light breeze is coming off the lake and I am bundled in a warm, black blanket scarf. Myeengun-onse and Bishiw-onse are both napping next to me. I have gratitude for a great many things today, one of which is being given the opportunity to share my story and speak about many of the relationships that guide and empower me.

Although I am only at the beginning of my journey, each day Gichi Gami calls me to act, to love, honour, protect and care for her as she does me. My relationship with water is exactly what gives me the focus, drive, strength, confidence and peace of mind to get me through each day. Water is a gift. Water is life.

It has taken me many years to grieve the death of my father. Although I have healed in many ways, I am told that grief never really leaves us. Shortly after he passed, I began having incredibly vivid dreams about him — dreams so tangible that I was unsure upon rising if he was dead or alive. He would speak to me, console me, laugh with me. I would wake up in a sorrowful daze, unsure which reality was true.

When we first began our canoe expedition, I recall jumping into the frigid May waters of the Kichi Sibi and having a panic attack because I couldn’t stop imagining my father in his final moments. The experience shook me to my core. But as one Elder so graciously reminded me, tears allow us to heal — they are one of water’s many ways of taking care of us.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the September/October 2023 Issue

Environment

How a cocktail of invasive species and global change is altering the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River ecosystem

People & Culture

A century after the first woman was elected to the Canadian Parliament, one of the most prominent figures in present-day politics shares her thoughts on how to amplify diverse voices in the Commons

Travel

Named after the south star, Octantis is Viking’s first expedition ship, which incorporates visits to Indigenous communities, supports environmental protection and more

People & Culture

“We were tired of hiding behind trees.” The ebb and flow of Métis history as it has unfolded on Ontario’s shores