People & Culture

Interview: Ry Moran on truth, reconciliation and his hopes for Canada at 200

The director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation reflects on Indigenous progress in 2017 and looks ahead to 2067

- 1163 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

For my father and me, these journeys are both personal and political

My alarm sounds at 3:45 a.m. — so early it might be considered night. There’s only one bed in my dad’s rental cottage in Shelton, Wash., so when I visit, we choose sides. I roll over, smacking him with my forearm, waking him, too.

I have work to do. At 6 a.m., the Quinault Nation’s oceangoing canoe is setting out to sea on the Tribal Canoe Journey, an annual trans-national Indigenous voyage and gathering in the Pacific Northwest. Of 87 participating canoes, the Quinault were scheduled to voyage farthest, and I want to cover their departure. Their reservation is two hours’ drive west of my dad’s place on the Olympic Peninsula, so we need to get on the road.

I haven’t communicated my early departure imperative to my father clearly enough. As I hop into my jeans, he ambles into the kitchen to put on a pot of coffee, then into the bathroom to lather his face and shave his stubble. While I march out to the car, my ears catch the familiar flick of the lighter followed by a deep inhale as dad sparks a one-hitter.

My dad is an artist — carver, sculptor, printmaker, magician — suffering from chronic back pain. Marijuana, legal in Washington, stokes his imagination and soothes his pain.

“We are going to be late!” I tell him. By the time we leave at 4:15 a.m., I am thoroughly exasperated. I am wrong. We barrel down backwoods highways, pulling up to the Quinault launch point with time to spare.

For two years running, the canoe journey has brought my father and me together, reminding us of who and how we love, and what it means to be Indigenous men. For the last two years, we’ve joined the Squaxin Island Canoe Family on this remarkable voyage. Squaxin Island is just one of dozens of communities that participate in the canoe journey. Every year since 1993, canoe families have departed from home waters throughout the Pacific Northwest on a collective odyssey to reclaim tradition and territory.

This year, our journey had begun on July 17 at Arcadia Point, Wash. — traditional territory of the Squaxin Island Tribe — and ends dozens of days and hundreds of kilometres later in the waters of the Wei Wai Kum First Nation in Campbell River, B.C. For the two of us, honoured to be welcomed by our Squaxin Island relatives, these journeys are both personal and political.

I get some of my best material from the trip on the Quinault reservation that morning of July 18. As the lone Quinault canoe prepares to set out to sea just below Point Grenville, I listen to Harold Curley, an elder and direct descendant of legendary Chief Taholah, who signed the 1855 Quinault Treaty establishing this reservation.

“Did you hear the story of the Spaniards coming out here in a great big battle ship?” he asks, looking out to sea.

In 1775, the Spanish Empire sent a two-ship expedition from Mexico captained by Basque explorer Bruno de Heceta to claim the Pacific Northwest over British, Russian and French rivals. The Spanish came ashore at this beach in Quinault territory on July 12 that year — a summer day just like this one — becoming the first Europeans to set foot in what is now Washington state.

“What happened is they came here, and there was nine Indians who was up there cooking crabs and clams,” he explains, gesturing at Point Grenville. “They invited [the Spanish] in, but they didn’t want to eat. Instead, they went over here and planted a cross in the name of King Carlos III.”

According to the Spanish, Quinault territory was now part of Mexico and the Kingdom of Spain. According to the Quinault, this territory is, and always has been, jurisdiction of the Quinault Indian Nation.

“The next morning, [the Spanish] came in and they went off chopping wood to fix a broken mast,” he continues. “So, they sent in a johnboat, and the narrator [a crewmember who logged the day’s events] on that ship (there were about two or three narrators in each ship) said that there was 300 savages came out of the woods and came on them and then [the Spanish] tried to chase them away by shooting the cannons and everything, and they just seen their seven men lost.”

The Spanish named the point at the end of the beach “Punta de los Martires” (Point of the Martyrs), after their fallen compatriots. Bruno de Heceta never again visited Quinault territory.

“I have two cannonballs at home from that johnboat,” says Curley, pausing to let the weight of this little-known history sink in — two cannonballs fired at his ancestors on this very beach. “Ain’t that something?”

As I took in Curley’s remarkable story — in which the Spaniards failed and his family passed on cannonballs that missed their targets like souvenirs, I saw my dad out of the corner of my eye, standing proud — and a little stoned.

My father’s friend Frank Brown from Bella Bella is a trickster, of sorts.

According to ancient oral histories of the Pacific Northwest, the world was born from curiosity and mischief. Raven stole the sun, moon, stars and water from Creator. Coyote’s schemes turned the land and coyote himself from supernatural to worldly. As these tricksters wandered the Earth looking for food, treasure and love, propelling change and finding trouble, they made our planet into what it is today.

These stories are mostly characterized as legends or fables — thereby infantilizing them. But I think they are better understood as metaphors, offering poetic theses about who changes society and the planet, and how. In a world shaped by Hollywood narratives (the Rebels blow up the Death Star, the Avengers save the world), trickster stories offer explanations that are complicated, ambiguous and often ironic. Change happens through actions intentional and coincidental, clever and lucky, noble and cunning. Change-makers stand at the edge of one world, forming the next from whatever is at hand — especially pilfered materials.

While Brown and my father were young bucks running the streets of Vancouver, Brown organized the first symbolic canoe journey as part of Expo 86, the world’s fair in Vancouver that coincided with the city’s centennial. In 1984, Brown, a college student working at the Vancouver Aboriginal Friendship Centre, received a request from the city’s mayor for native participation in the exposition. Brown jumped at the opportunity. Expo wasn’t about revitalizing native culture, but Brown was.

“My interest was to represent ourselves, to show the first form of transportation and communication on the coast,” says Brown. “And for us, that was the glwa, or oceangoing canoe.”

The traditional oceangoing canoe is a communal vessel. Groups work together to fell and carve old-growth cedar. Every year, dozens of hands come together to carry watercraft to the sea. Teams of pullers paddling in unison pilot their way through churning tides, crashing waves and swift currents to traverse the coastal seascape that connects ocean to continent and past to future.

Post-Expo, the idea continued to spread. In 1989, the late Emmett Oliver of the Quinault Nation organized the Paddle to Seattle to ensure native representation during Washington state’s centennial. Ironically, twice it was the celebration of a century of colonial settlement that provided the platform for a resurgence of Indigenous canoes. I think of these historical moments as Thanksgivings in reverse — Indigenous people appropriating colonial celebrations to bring back traditional life-ways and reclaim connections to ancestral lands.

In 1993, Brown’s home community of Bella Bella hosted the first annual Qatuwas, or “people gathering together,” in conjunction with the International Year of the World’s Indigenous People. The gathering, thereafter known as the

Tribal Canoe Journey, has been held every year since.

“The people of the coast have embraced the vessel as an empowering tool in our process of decolonization,” says Brown. “However, it does not come without a challenge, and that’s what our young people need: to challenge themselves through thinking through, and working through, the process of getting from one destination to another.”

***

Our skipper guides the canoe’s bow into the onrushing white waters of Dodd’s Narrows, a treacherous coastal bottleneck between Vancouver Island and Gabriola Island just south of Nanaimo, B.C.

My father braces his foot against mine and leans forward, poised to charge into battle against the mighty Salish Sea. Dad, veteran of rez fisticuffs, inheritor of a centuries-long resistance against annihilation that bent his body and spirit into permanent defensive pride, has a warrior’s heart. He is 5’10”, but in these moments, even as his 57-year-old frame fades, his presence is much taller.

Our bodies are failing — my father’s from decades of carving hulking tree trunks and downing thousands of bottles, mine from a bad case of coxsackievirus, with accompanying flu-like symptoms, that landed me in the emergency room just a few days prior — but our spirits are unyielding. The skipper calls out 100, 200, then 300 “power pulls” — hard, prayerful strokes, to muscle our crew of 11 through the rough waters of the narrows and the hard knocks of life. Despite collective struggle, our canoe barely progresses. Dad swears in pain and frustration. After 500 power pulls, we stop counting altogether and break into song.

“Wi-la, Wi-la, Wi-la-wi!” our young pacesetter calls out from the bow.

“He-yo!” we respond from the stern.

“Hu! Hu! Hu!”

After 20 minutes of backbreaking work, we pull through the far side of the narrows. Along the voyage, crews sing paddle songs, new and old, to keep rhythm and uplift spirit. After each long day of pulling under the summer sun, canoes, support boats and road crews stop to visit with their hosts, rekindling connections that criss-cross the Northwest, extending north and south, to the inland and out onto the sea, like the warp and weft of the traditional cedar bark hats the pullers wear on the water. It takes days and even weeks of paddling across hundreds of kilometres of ocean for the canoes to reach each year’s final port-of-call in early August. There, the participants celebrate with a week of potlatch singing, dancing, feasting and giveaways.

Contrast this with the modern world that is habituated to jets, trains, ships and automobiles, where travel is solo or in small groups with little labour entailed. Spaces traversed are liminal, sometimes termed “fly-over country.” The destination is what matters. If you need to get from point A to point B, buy a ticket or fill up the tank, grab a bag and go.

The traditional oceangoing canoe, meanwhile, is a communal vessel. Groups work together to fell and carve old-growth cedar, ideal for a hull. Generations of master carvers have fine-tuned the canoe’s dynamic form. Meticulous craft and care go into burning the log hollow and shaping it with an adze. Every year, dozens of hands come together to carry watercraft to the sea. Teams of pullers paddling in unison pilot their way through churning tides, crashing waves and swift currents to traverse the coastal seascape that connects ocean to continent and past to future.

“This canoe movement is the most significant gathering of Indigenous Peoples in the Americas today,” says Brown.

“What it does is it endears [our territories] into the hearts of our young people so that when it comes time and they’re called upon to stand up for those resources that we depend on, and that environment, then the community has a very strong ethic and a value and a commitment, because they’re practising the lifestyle.”

Not long ago, generations of Indigenous children were abducted and incarcerated in residential schools. Their languages and cultures were quite literally beaten out of them in an organized effort to “kill the Indian in the child.” At the same time, Indigenous cultural and spiritual gatherings were outlawed under the potlatch ban in 1886, which remained in effect until 1951.

Both of my father’s parents were sent to residential schools. He was born in a residential school hospital and spent his childhood bouncing from one home to the next. He has lived a life of intergenerational trauma, struggling to be a father. His absence from my childhood left me — the next generation — with an enduring wound where a parent should have been.

Yet despite persistent efforts to stamp out Indigenous cultures and communities — to make my grandparents and my father forget who they are — today, Indigenous people such as me are born into a world where the beauty and power of who we are is embraced. In the Pacific Northwest, the canoe is central to this resurgence. It brings communities together to paddle ancestral waterways. It challenges elders and youth to revive old songs and dances and compose new ones so they can paddle onto their neighbours’ shores, proudly singing-in the spirits of our ancestors. In an age of digital relationships, it brings families together to celebrate and work through troubles. It reintroduces people to water in an elemental way, reminding us that water sustains life.

This is a messy process. It’s not a weekly church service. After generations of colonial trauma, native families and communities have serious issues to work through over early morning canoe departures, cannonballs that memorialize our trickster past and marijuana bowls that signify our painful present.

But if we rise to the challenge and learn to live and work together again, the resurgence of Indigenous values and teachings just might carry transformative potential for a world hurtling toward ecological disaster. We are the progeny of tricksters, after all. And this is how tricksters change the world.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

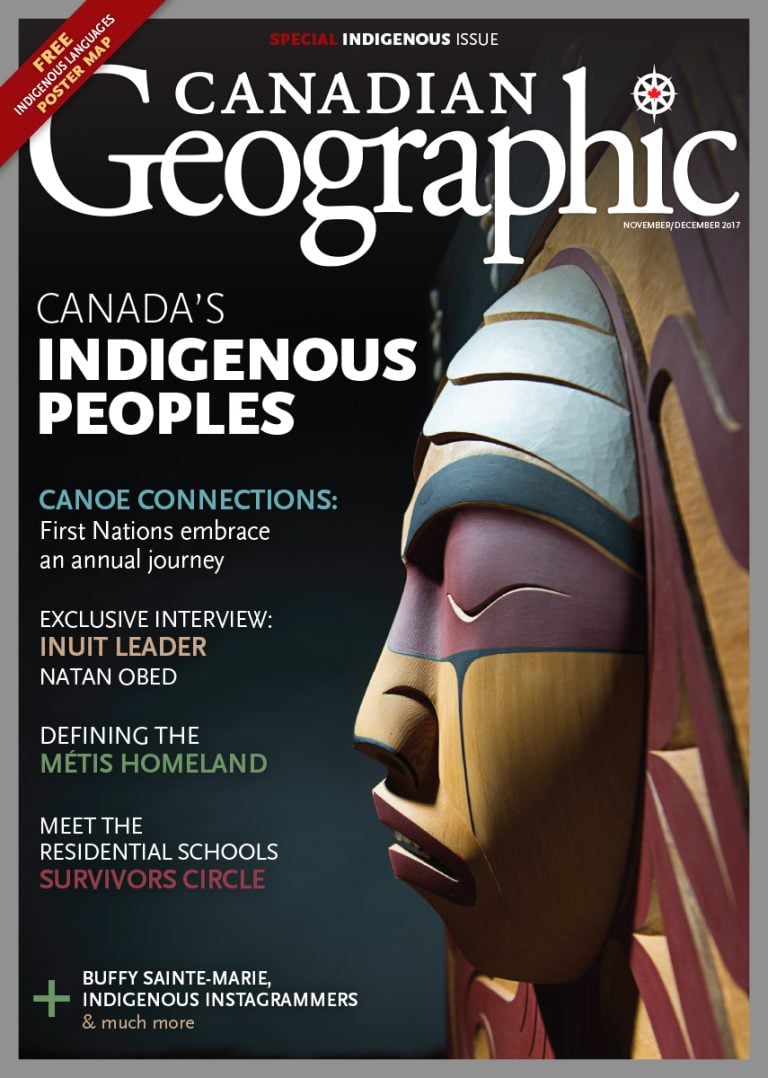

This story is from the November/December 2017 Issue

People & Culture

The director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation reflects on Indigenous progress in 2017 and looks ahead to 2067

History

Canadian Canoe Museum explores the link between paddling and romance

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

Images from an annual odyssey to reclaim tradition and territory in the Pacific Northwest