History

Royal Canadian Geographical Society CEO John Geiger gives a sneak peek of this year’s Franklin search

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

- 1638 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

If you’ve ever bobbed up and down on the waves, out of sight of land, you know that our planet’s oceans can seem endless. Their surface vastness is only the beginning. Beneath the waves, their volume is almost inconceivable. Without modern technology, searching for a ship that sank at a random point in the ocean would be an exercise in pointlessness, but with modern technology at our disposal, Canadians are zeroing in on our most famous undiscovered wrecks.

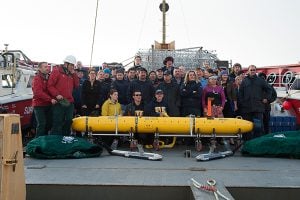

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles

Even the best cold-water diving gear has its limitations, and even most intrepid diver is only human. Underwater Autonomous Vehicles let researchers go deeper into the cold waters of the Arctic Ocean, and stay there longer than any human could hope to. These unmanned submarines can be controlled from the surface and operate independently. With flood lights and onboard cameras, AUVs can transmit images from depths where no diver could survive.

Marine Geophysics

Geophysical technologies help us understand more about what lies in the ocean’s depths. They can also help locate shipwrecks by helping searchers better know what lies beneath the waves, so they can know where to look for lost ships like the Erebus and Terror.

Synthetic Aperture Sonar

Able to produce images with up to ten times the resolution than conventional sonar, Synthetic Aperture Sonar was developed by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to locate deadly marine mines. Numerous soundings (pings) are sent from a single transducer toward a small area on ocean floor. The time of each sounding’s return trip is recorded, and the data that returns from the spot processed by high powered computer to create an ultra high resolution image of what lies below.

Multibeam Sonar

High frequency pulses of sound are sent from a ship toward the sea floor. The longer those pulses take to return, the deeper the water is. A computer on board records the data, then uses it to create a map of the different depths, showing researchers the location of the ridges and depressions that make up the topography of the ocean floor.

Side Scan Sonar

Once researchers know roughly what the depth of the ocean is, side scan sonar can give them a clearer picture of exactly what is creating the rising and falling topography below. A transducer is lowered into the sea, and sends out pulses of sound at the sea floor that surrounds it. Recording the echoes that return gives researchers a clear picture of exactly what’s down there. Side scan sonar can reveal the shape of a shipwreck, but far more often will reveal random boulder or underwater ridge.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

History

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

History

Arctic historian Ken McGoogan takes an in-depth, contemporary perspective on the legacy of Sir John Franklin, offering a new explanation of the famous Northern mystery

History

This year's search is about much more than underwater archaeology. The Victoria Strait Expedition will contribute to northern science and communities.

People & Culture

On April 12, Franklin enthusiasts had a rare opportunity to come together in the same room as The Royal Canadian Geographical Society presented their 2016 Can Geo Talks