“Who the hell is Louise Arner Boyd?”

Joanna Kafarowski probably won’t blame you for saying that. After all, a not-dissimilar thought ran through the Canadian author’s head when she first learned about Boyd’s Arctic exploits in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s in 2005.

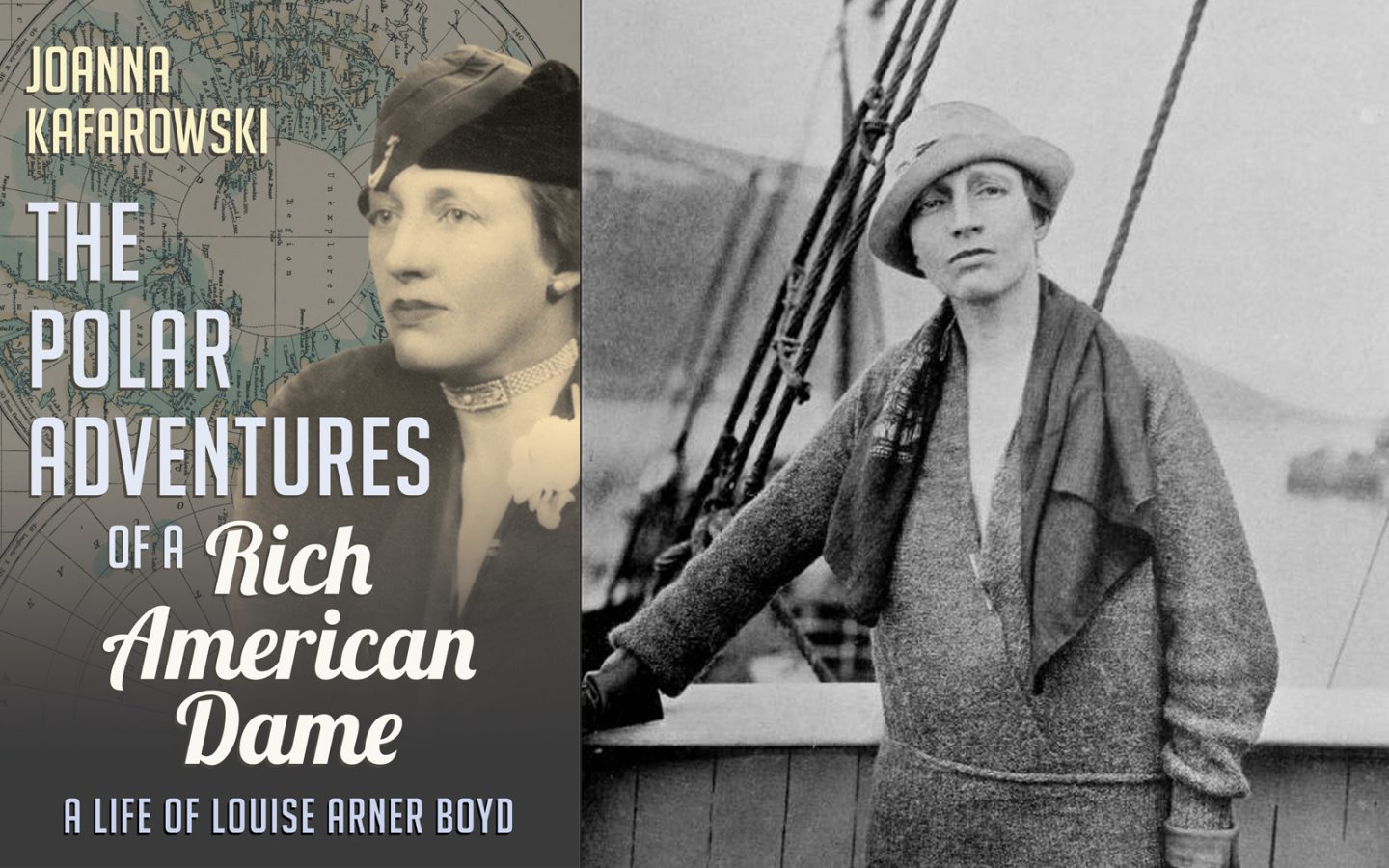

“I happened upon her name as someone who had been engaged in expeditions around Greenland in particular, and was just very intrigued by what she accomplished and wondered why there was no other information available,” says Kafarowski, whose new book The Polar Adventures of a Rich American Dame: A Life of Louise Arner Boyd was published last month after more than 10 years of research and writing. “That length of time really speaks to how strongly I feel about Ms. Boyd, because I happen to have a very short attention span,” jokes Kafarowski. “So apart from my marriage, this is really something that I’ve stayed with for a long time.”

Here, Kafarowski discusses everything from Boyd’s background to her much-lauded (and nearly forgotten) career as an Arctic explorer.

On what intrigued her about Louise Arner Boyd

One of the things I find most intriguing about her is that she really lived a double life. She grew up in a wealthy home and was expected to marry and continue being involved in society as a California grand dame. But throughout her whole life she negotiated a balance between that responsibility and her role as a polar explorer, which was her real passion. She’d return from the Arctic and do promotional work or some lecturing, but she never dropped her role as a society hostess.

She obviously wasn’t someone who had been brought up in the North, and had never seen snow or ice before she was an adult, which was also an aspect that interested me — why was she even drawn to go to those remote regions of the Arctic? I think, too, that part of what drew me to her story was that I’ve always felt passionate about the North and its landscape, and when I started reading more about her and read some of the books that she’d written, I could see she felt the same way. So in a sense, I felt like I’d found a kindred spirit.

On what drew Boyd to the Arctic

There were a few elements that combined to excite her interest. She mentioned very early on in her life that the lack of snow and ice in California played a role, but she’d also had an adventurous childhood, growing up hunting and riding and fishing with her two older brothers — she was quite a tomboy from an early age. So we know she had a predilection for exploring and adventure. But, having been born in 1887, she also grew up in a period that was the twilight of the golden years of polar exploration, and would have read or heard about stories such as George Washington De Long and the Jeannette expedition and the Greely expedition — the latter the kind of grisly tale that certainly would have intrigued a young girl and her older brothers. Exposure to those types of stories continued when she was a young woman caring for her parents between 1906 and 1920, a period when the controversy about whether Robert Peary or Frederick Cook, both Americans, had conquered the North Pole emerged and played out not just in the United States but internationally.

On Boyd’s expeditions and accomplishments

Over her seven expeditions [1926, 1928, 1931, 1933, 1937, 1938 and 1941. —Ed.] she accumulated a vast body of data, particularly on the coastal areas of East Greenland. She and the scientists she hired surveyed, mapped, took thousands of photographs, made countless hours of film and did work in geology, botany, oceanography and geomorphology that’s still being used by scientists today.

Her 1928 expedition was probably her most formative. She was sailing to Franz Josef Land and had arrived in Norway, where she learned that Roald Amundsen, the iconic Norwegian explorer, had gone missing while flying to rescue another explorer near Spitsbergen. Boyd put her ship and her crew at the disposal of the Norwegian government, taking part in an international rescue mission along with 15 other vessels. During the search for Amundsen, who was never found, Boyd met and worked with well-known polar aviators [In 1955, Boyd would become the first woman to reach the North Pole by air. —Ed.], explorers and scientists, and her courage and perseverance was recognized, which is something that I think really propelled her forward. If Amundsen hadn’t disappeared and she had not been in that place at that time, then her life and her involvement in expeditionary work would have been quite different.

On what she admires about Boyd

She was entirely self-taught because her education had been modest, which wasn’t unusual for a woman of her time and her class. From her first expedition in 1926, she started a lifelong period of study and acquiring an extensive library of Arctic materials, which she used to learn about botany, geology and geomorphology. So although she didn’t have a degree, she managed to hold her own with the scientists on her expeditions. I admire her courage, her chutzpah, for doing so, because at the time many of the people she chose to work with made assumptions about her and her abilities, and certainly felt she was a dilettante rather than a serious explorer. Yet over time her dedication to her work and her growing abilities won her the respect of not only the people she worked with on the expeditions but also that of her male contemporaries.