Wildlife

Do not disturb: Practicing ethical wildlife photography

Wildlife photographers on the thrill of the chase — and the importance of setting ethical guidelines

- 2849 words

- 12 minutes

People & Culture

As the country retreated to physical distancing in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, our interactions with geography altered dramatically. A collection of images that captured how Canadian life changed.

Michelle Valberg was on Vancouver Island photographing coastal sea wolves and the annual herring run when the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic this past March.

The disease caused by the novel coronavirus that emerged in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019 had been in Canada since late January, but had at first seemed to be an obscure threat affecting mainly international travellers. On March 13, Valberg, a Canadian Geographic photographer-in-residence, boarded a flight back to the mainland — and emerged into a reality very different from the lush, colourful wilderness she had left behind.

“I remember landing in Vancouver and feeling the ominous spirit around and how quiet people were,” she says. “It felt like I stepped into a black and white world.”

That same day, Quebec became the first province in the country to declare a state of emergency related to the pandemic. Within a week, every province and territory had followed suit, each implementing a range of directives aimed at limiting the spread of the virus.

Schools, restaurants, bars, malls, movie theatres and other public gathering places were closed. Concerts and sporting events were cancelled. Canadians abroad were urged to come home as quickly as possible, as the world’s borders slammed shut.

Valberg made it home to Ottawa, completed a 14-day quarantine, then, like millions of others across Canada and around the planet, she entered a period of voluntary self-isolation from family and friends.

These weeks will be remembered as an unprecedented hardship. Rituals that give our lives structure and meaning — weddings, birthday parties, funerals — were off-limits. Mundane activities such as shopping for groceries or riding public transit suddenly seemed fraught with danger. In April alone, nearly two million Canadians lost their jobs. By the end of that month, Canada had surpassed 50,000 cases of COVID-19 and some 2,500 people had died from the virus, many of the cases and deaths linked to outbreaks among the elderly and vulnerable in long-term care facilities.

Yet we adapted. Through daily press conferences with public health officials, we learned a new vocabulary — flatten the curve, physical distancing, test-and-trace. Working and socializing alike went virtual by way of videoconferencing platforms. As temperatures warmed through the spring, cities made space for safe outdoor recreation. Some of these changes may prove permanent.

Nature, too, benefited from the pause in our normal activities. Air quality improved dramatically in parts of the world that normally see dangerous levels of pollution. Researchers in B.C. found the waters off the coast to be 15 per cent quieter than usual, a result of reduced shipping and fishing traffic, offering a new opportunity to study the connection between noise and stress in whales. From foxes in downtown Toronto to wild turkeys in Montreal, sightings of wildlife in urban areas increased, and in closed provincial and national parks, animals returned to trails that would ordinarily be packed with hikers.

Faced with the loss of her studio business and travel opportunities, Valberg found solace in her art, venturing out alone to capture images of empty streets, backyard birds and the gradual transition from winter to spring.

“I just needed to stay creative,” she says. “I needed to get out of the uncertainty and the scared feelings I was having.”

Others, like Yellowknife photographer Pat Kane, were also moved to use their skills to document the historic moment. In mid-March, Kane began creating a series of portraits of people isolating at home, shot through windows or below balconies. For Yellowknifers, who rely on each other to cope with the long, harsh winters, the concept of self-isolation is “completely strange,” he says, yet it was understood that it was imperative to protect vulnerable northern communities. As of June, the Northwest Territories had recorded just five cases of COVID-19 and no deaths.

Pat Kane created a series of pandemic family portraits through home windows in Yellowknife.

While we await a medical solution to the virus, and as localized outbreaks of COVID-19 continue to pop up, we may need to learn to live with precautions such as wearing masks in public and limiting social contact. The origins of COVID-19 also raise difficult questions about our stewardship of the natural world. The images collected here, by photographers from around the country, may serve as a reminder of what we sacrificed for our safety — and what we stand to gain if we heed the lessons of the early days of the pandemic.

“That’s the beauty of photography,” says Valberg. “It gives you the opportunity to see things in a different way.”

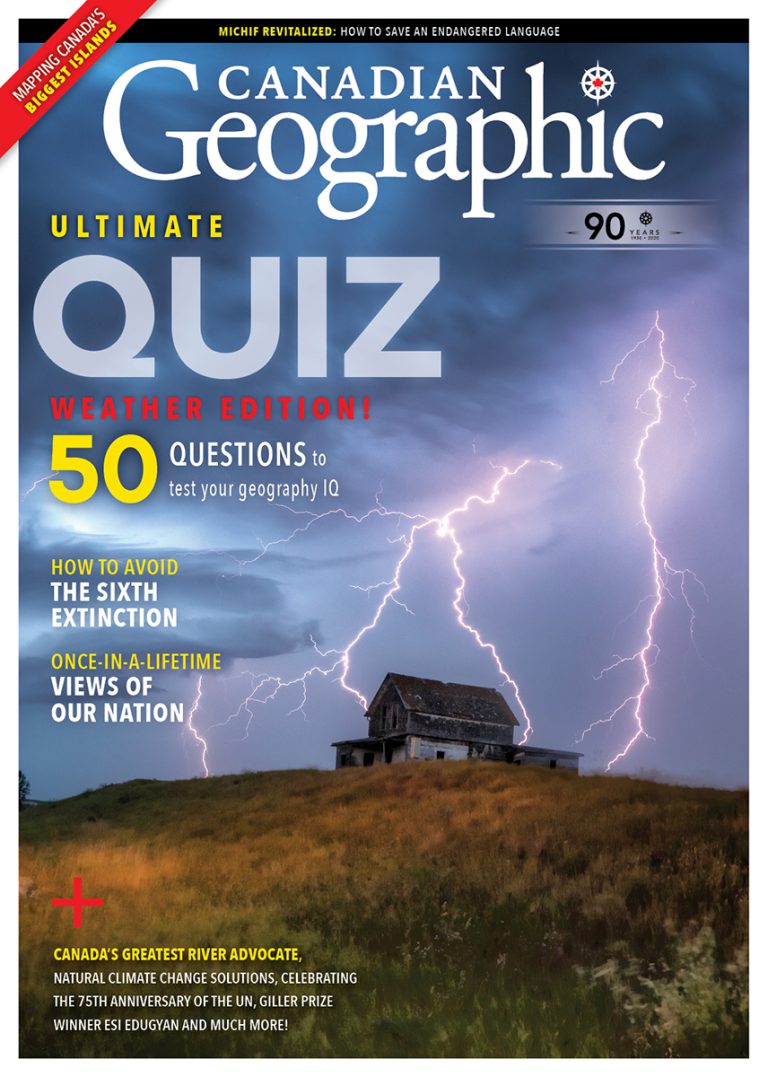

This story is from the September/October 2020 Issue

Wildlife

Wildlife photographers on the thrill of the chase — and the importance of setting ethical guidelines

People & Culture

For unhoused residents and those who help them, the pandemic was another wave in a rising tide of challenges

People & Culture

These 10 members of Canadian Geographic’s online Photo Club are making waves with their unique perspectives on Canadian wildlife and landscapes

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved