Environment

Why mountains matter in Canada

They sustain us, enrich our lives and inspire us

- 1287 words

- 6 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Love is in the air for the mountain pine beetle, but it may not lead to a happy ending. Scientists have begun to use the insect’s pheromones against them in an effort to curb the spread of the invasive species in jack pines.

Nadir Erbilgin, an associate professor and forest entomologist at the University of Alberta, is working with a team to use traps baited with a synthetic version of the beetle’s pheromones to monitor populations in different areas. If all goes to plan, the same pheromones that draw love-stricken beetles to certain trees may be used to kill them off.

Like many species, mountain pine beetles rely on chemical aromas to inform them of possible mating opportunities. Once they find a suitable tree, females release an aroma that attracts males and even other females. Mass colonization of the tree usually only takes a few days, as beetles are also drawn to the scent of a stress chemical released by the trees as a result of the beetles’ attack.

“These insects must kill the host tree to reproduce,” Erbilgin says.

To monitor beetle infestations and possibly curb their spread, Erbilgin’s team has created a synthetic version of this aggregation pheromone and put it into pine trees. The team can then estimate the total beetle populations in a given area based on the number of beetles they trap within a fixed period of time. “If you trap something like 1,000 beetles, you should be concerned,” Erbilgin says.

But there’s a catch: once a tree becomes overpopulated with beetles, females make an abrupt attitude adjustment and begin to emit a new anti-aggregation pheromone that actually repels the beetles in order to reduce competition for resources and potential mates.

Erdilgin says they’ve experimented with using a synthetic version of this second pheromone to see if they can repel the beetle from certain areas, but they weren’t happy with the results. “You’ve got to be careful; you might repel the beetle from one area and the beetles will start killing trees elsewhere.”

Beyond monitoring, he says there is little use these methods could have in stopping the kind of beetle epidemic that has infested lodgepole pines in British Columbia. But the aggregation pheromones could possibly control the spread of smaller populations of the beetle such as those that target jack pine in Alberta.

But for now the process is still expensive and labour-intensive, and Erbilgin says controlling the beetle’s spread is an upward battle.

“Dealing with these tree-killing mountain pine beetles is more difficult than killing cancer,” he says. “There are something like a trillion of these beetles and they are good flyers — they fly over the Rocky Mountains.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

They sustain us, enrich our lives and inspire us

Environment

Since the 1990s, mountain pine beetles have invaded more than 18 million hectares of forest in Western Canada. Researchers now have a better understanding of how this is done.

Exploration

A century after a Canadian was instrumental in charting the world's highest peak, a fellow Canadian reflects on the magnetism of Everest

Exploration

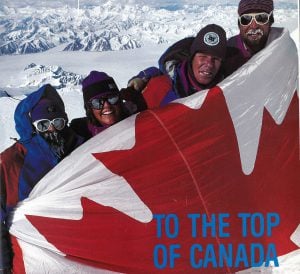

In 1992, a team backed by The Royal Canadian Geographical Society became the first to accurately measure the height of Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak