Science & Tech

UN declares International Day of Women in Science

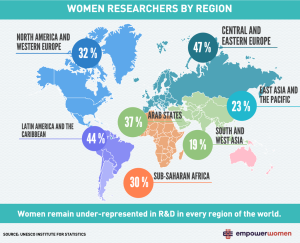

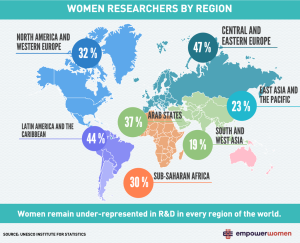

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

- 472 words

- 2 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

By the 1970s, computers had evolved to the point where a future free of human weather forecasters seemed possible. Numerical models — weather translated into algorithms and equations — would predict quickly and accurately, leaving meteorologists with little to do but find new jobs. Looking back at that time, David Sills, an Environment Canada severe-weather scientist based in Toronto, says enough trust was being placed in technology that it threatened to eat away at strengths only humans can bring to the discipline. It’s still happening. “A lot of the modelling community really doesn’t see a role for the forecaster within 5 to 10 years,” says Sills. “But in my opinion, we’re still quite far away from being able to replace the forecaster completely with automated systems.” That’s especially true with severe weather, despite today’s climate of cutbacks in Canada’s meteorological services.

Like any living, breathing scientist, Sills is naturally inclined to vouch for carbon- based systems rather than siliconbased. But he also has data demonstrating the need for, and clearly illustrating the challenge of, short-term forecasting in one of the world’s largest and least populous nations.

Often, storm initiation is a phenomenon small enough to evade Canada’s network of monitoring facilities. Following a restructuring at Environment Canada in 2003, for example, no storm-prediction centre in the country is responsible for less than one million square kilometres — in fact, the Prairie and Arctic sector, handled out of Edmonton and Winnipeg, spans more than eight million square kilometres. Regardless of the size of these territories, there are gaps between “operational networks,” which are designed for forecasting, and the small-scale features and processes that influence our weather. A recent project called Unstable (Understanding Severe Thunderstorms and Alberta Boundary Layers Experiment) highlighted the difference.

“When we do a field campaign, it gives us the opportunity to fill in the holes and try to get a sense of what’s going on that forecasters may not be able to see,” says Neil Taylor, the co-principal investigator with Sills on Unstable. In 2008, the Edmonton-based weather scientist visited Alberta’s foothills region, adjacent to the Rockies, on a fact-finding mission for forecasters who struggled to predict storms there — a common challenge for forecasters in all types of topography. The area is the lightning capital of the Prairies, a staging ground for storms that rumble east to the busy Edmonton-Calgary corridor, where they’ve wreaked havoc measurable in millions of dollars and more than two dozen lives.

“When forecasters see something happen over and over, they can develop a rule of thumb,” says Sills. “But that doesn’t mean they understand why it happens.”

As in other parts of Canada, the cause of foothills storms was lodged in the hypothetical. Scientists know that moisture is fuel for the thunderstorm, but through projects such as Unstable they’re working to better understand the cause and effect. A summer of direct observation in the foothills in a Toyota Prius outfitted with weather-sampling equipment revealed what meteorologists call a “dryline,” with warmer dry air to the west and cooler moist air to the east (which differs from a typical front, where the air on the cooler side tends to be drier as well). The dryline clash can occur over as little as a few hundred metres and can provide a trigger for storm development, says Taylor, while weather stations can be a few hundred kilometres apart.

Ground-level features like these can cause severe storms, and there’s only one way to learn about these storms to give forecasters information necessary to issue adequate warning. “You have to get out there,” says Taylor, “and sample them.”

That remains the basis of meteorology: it must be seen before it can be believed or fed into a computer. “Observational data are crucial,” explains Jason Milbrandt, a numerical weather-prediction research scientist at Environment Canada’s Meteorological Research Division in Dorval, Que. “The only way one can predict the future is by first having a reasonably good estimate of the present state.”

A health analogy can be made: only a proper understanding of the symptoms can determine the right diagnostic tool — in this case, a computer model — and only the right model can produce an accurate prognosis. With both physicians and meteorologists, the human capacity for pattern recognition and critical thinking remains vital to that process, regardless of the quality of technology. Without that, severe-weather prediction, which occurs within a window of a few hours, is little more than a computational guessing game.

With 776 job cuts announced last summer at Environment Canada, more than 150 of them scientists and engineers, Unstable researcher John Hanesiak worries about losing that personal touch. “We’re pushing the computer models too quickly, and we’re forgetting the human side,” says the University of Manitoba professor of atmospheric science. For him, the Alberta project argued for more people, more technology and further investigation of small-scale phenomena responsible for severe storms across the country, thereby delivering more value to Canadians. “What do we want as a basic service?” he asks, noting that universities can’t afford to carry the research load alone. “When does the cutting stop?”

Meanwhile, Environment Canada staff has made do. In 2004, for example, Sills began a summer program to plant weather scientists in forecasters’ offices to help transfer knowledge and tools from the field and to identify shortfalls in realtime severe-weather prediction.

A volunteer network of roughly 500 weather watchers known as CANWARN contributes as well. Trained to identify unique cloud features, members report their observations to Environment Canada via phone calls, amateur radio networks and, increasingly, submit photos via Twitter and Facebook. “I think, overall, we’ve done a pretty good job,” says Taylor of Canada’s severe-weather-prediction efforts.

Patience has certainly played a part. Planning and waiting for funding over a period of eight years preceded Unstable, and that was only the pilot, a $140,000 experiment in methodology as much as data gathering. Sills hoped for a follow-up in the next couple of years, but with recent austerity measures, “it’s not looking so good.” Even if Environment Canada has allocated $27 million over the next two years for improved forecasting, Sills struggles for a positive prognosis.

Hanesiak does too and maybe, even if inadvertently, foresees a gloomier horizon. The way he positions the human factor, it goes hand in hand with research output. Do projects such as Unstable convince the kinds of students who take Hanesiak’s storm-chaser course that there’s still a role worth pursuing in severe-weather forecasting? “There’s nothing like watching this thing come at you and blast you with cold air and strong winds,” says Hanesiak. Ultimately, could giving thrill-seekers purpose (along with funding and equipment) not only prove the modelling community wrong but also better protect the property and lives of Canadians?

“Every time you go out, you learn something,” says Hanesiak, a hint of excitement lifting his voice slightly. “Every storm is different.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)

Environment

Initially targeted at visitors and locals in Tofino and Ucluelet, B.C., the CoastSmart program could save lives along all Canadian coasts

Environment

Tracking the country’s extreme weather events to answer the question: are storms getting worse?