People & Culture

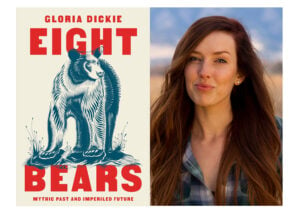

The truth about polar bears

Depending on whom you ask, the North’s sentinel species is either on the edge of extinction or an environmental success story. An in-depth look at the complicated, contradictory and controversial science behind the sound bites

- 4600 words

- 19 minutes