People & Culture

Kahkiihtwaam ee-pee-kiiweehtataahk: Bringing it back home again

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

- 6310 words

- 26 minutes

People & Culture

The former Canadian parliamentary poet laureate feels most grounded at Three Mile Plains, N.S.

When I was becoming a poet at 15 or 16, I had all the stimulation of Halifax, but I knew I needed to be at Three Mile Plains. Three Mile Plains is 70 kilometres northwest of Halifax on the way into Windsor town, where I was born. Black Nova Scotians have lived here since planters brought dozens of enslaved people around 1760. My own maternal family arrived on the South Shore in 1813 and migrated to Three Mile Plains a few years later.

The colonial government gave the impoverished Black people poor lots of land. It was not arable; it was swampy, rocky. But the people formed communities. No matter how much discrimination we faced, there was a sense of identity and literal groundedness on our piece of rotten terra firma. Because in slavery, you couldn’t own your children — they could be taken at any time and sold away, as could your parents. For former slaves now able to say, “that’s my piece of land, my horrible, non-productive, non-arable piece of land, but it’s mine; that’s my house, these are my children, that’s my husband and that’s my wife.” To have all these kinds of connections rooted in a place is powerful.

For me, my connection to Three Mile Plains was folklore, and the people’s experiences were the foundation for any writing I was going to do. When I walk on my own land in Three Mile Plains, I look up and all I see are tree branches until I get to Heaven. My crabapple trees, my spruce trees, my pine trees, my grass, my anthills, my beaver skeletons. All gloriously mine. And maybe one day still, I might build something there.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

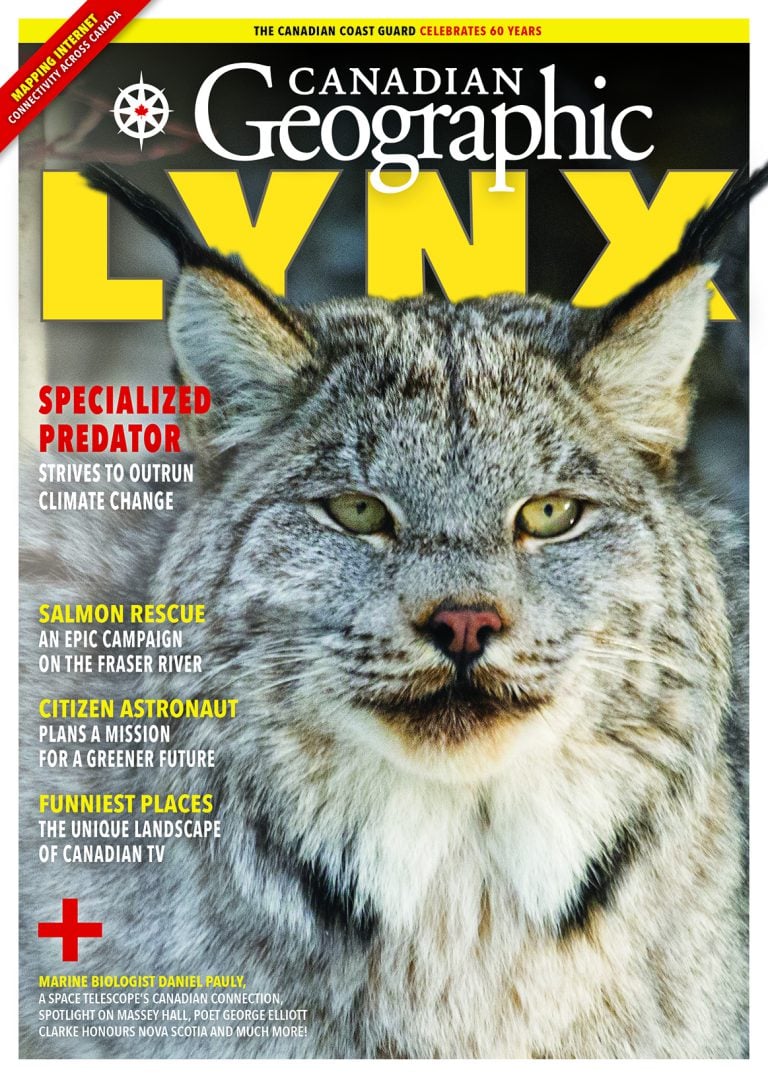

This story is from the January/February 2022 Issue

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

Canada’s former Poet Laureate gives us a tour of the cultural geography of Black Nova Scotia

Places

In Banff National Park, Alberta, as in protected areas across the country, managers find it difficult to balance the desire of people to experience wilderness with an imperative to conserve it

Travel

A pilgrimage to Kejimkujik reveals centuries-old connections between descendants of Nova Scotia’s first Scottish settlers and the Mi’kmaq who saved them