Environment

Inside the fight to protect the Arctic’s “Water Heart”

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

- 1693 words

- 7 minutes

Mapping

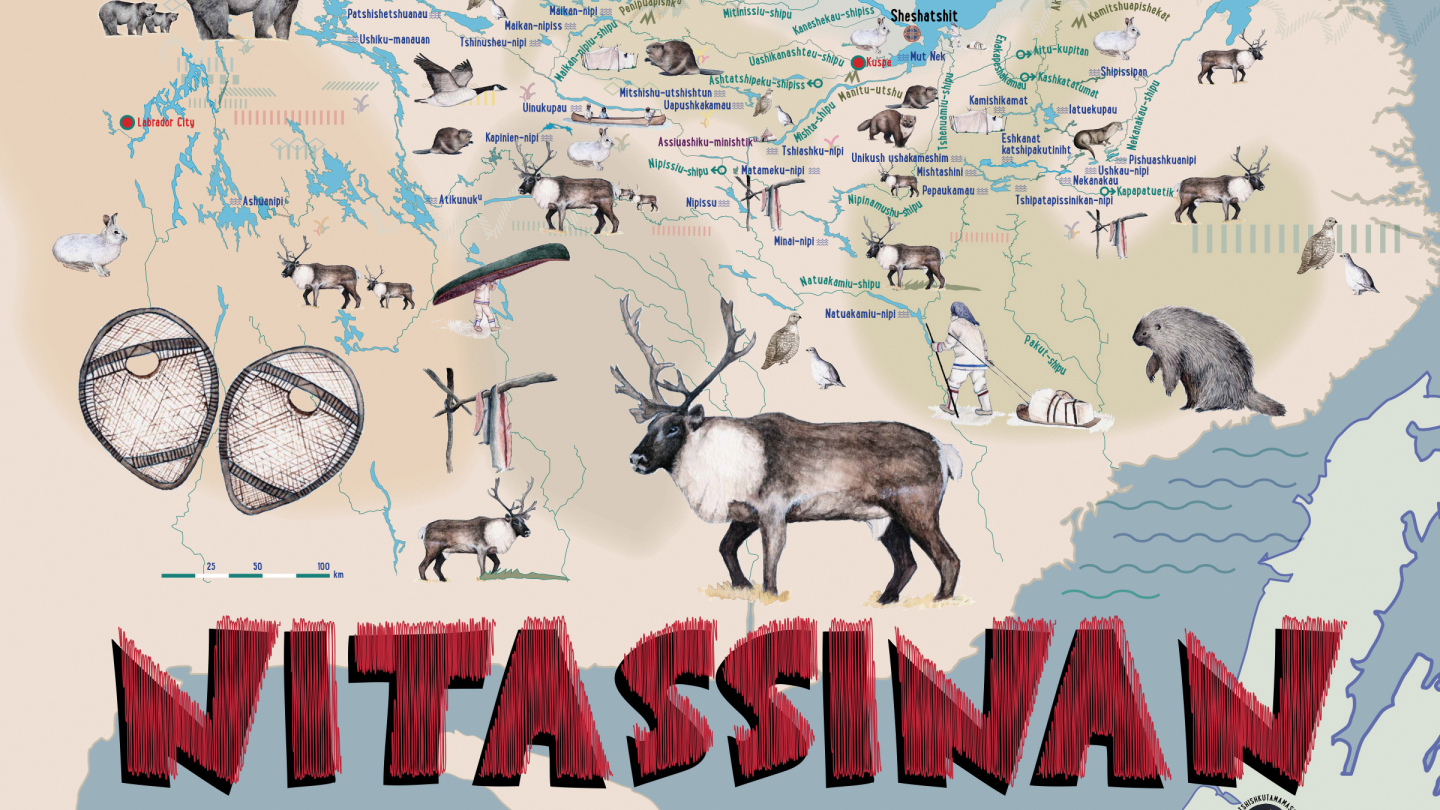

An Innu school board has created a map to pass on intergenerational knowledge to schoolchildren

It started with a few illustrated maps for two small schools. Two printed editions, one giant floor map and layers upon layers of watercolour later, the Nitassinan map project by Mamu Tshishkutamashutau Innu Education school board is grabbing attention across Canada.

Mushuau Innu Natuashish School and Sheshatshiu Innu School are nestled in the heart of Sango Bay, northern Labrador, and at the eastern end of Lake Melville, in central Labrador. At least, according to most maps. But the Innu, who have lived in these lands for thousands of years, know the land as Nitassinan — their homeland. “The Innu have been travelling all over the north shore of Quebec and Labrador since the beginnings of time,” says map illustrator and researcher Jolene Ashini. “A lot of the time, especially on reserves, we have teachers who come in who are not Innu. We get taught the Canadian, colonized, view of how things are done.”

The mandate was clear: create a map representing the Innu world view, both old and new — including names for more contemporary places that didn’t exist in the traditional Innu world. It meant no boundaries or borders. And it meant tapping into the vast knowledge banks of the community’s Elders. “We took all of these huge maps and plastered them all over the wall,” says Ashini. “We asked people, especially Elders, about where they had been previously and what were the names of the places they recalled and what animals they saw there.” The work built on 40 years of prior research and interviews by the Innu Nation that had yielded roughly 1,200 place names.

The painting process itself was no small feat. Ashini, along with co-researcher and cartographer Chelsee Arbour, had to distill all the information from the interviews into a list of places and animals to include. Ashini then began sketching rough drafts, before moving on to the lengthy process of painting and drying, building up layers of watercolour paint to create realistic final paintings. Once the map was ready, the schools invited Elders into the classroom.

One of those Elders was 76-year-old Elizabeth Tshaukuesh Penashue. “I showed the students where their grandparents and ancestors came from, the routes they took, the birth places and where some burial grounds and hunting territories were,” says Penashue. “The students were very interested in the animals, so I talked about how we hunted the porcupine, for example, and how we cleaned it.”

Penashue had never seen a map with Innu names and culture before. “We’ve been living this way for many generations,” she says. “It’s important to pass down these teachings so that children don’t lose their culture.”

The map itself was the result of different generations of Innu working together. While Penashue’s knowledge helped form the map, it was her daughter who spearheaded the project — Kanani Davis, the CEO of Mamu Tshishkutamashutau Innu Education.

The reception has been overwhelmingly positive, with calls for copies coming from all over the province and even over the border, in Quebec. Other First Nations have been in touch, emphasizing that this kind of project should be done in all schools in all communities. The demand caught Davis off guard at first. “We didn’t think we were going to get this much interest,” she says. “We just wanted to show the map to students, show them where their ancestors hunted, their burial grounds and their birthplaces. This has exceeded our expectations.”

Surprise, however, soon gave way to vision. And like the map, Davis’ vision has no bounds. Already, a printing of 200 copies of the second edition of the map (including more animals) is in the works, along with an expanded school curriculum focusing on the map’s animals — and most exciting of all, a giant floor map of Nitassinan is currently being piloted in schools. “We want the students to walk on the map with an Elder and learn the places and stories,” says Davis. “It’s more symbolic. More meaningful.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the November/December 2021 Issue

Environment

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe

People & Culture

For generations, hunting, and the deep connection to the land it creates, has been a mainstay of Inuit culture. As the coastline changes rapidly—reshaping the marine landscape and jeopardizing the hunt—Inuit youth are charting ways to preserve the hunt, and their identity.

People & Culture

Indigenous knowledge allowed ecosystems to thrive for millennia — and now it’s finally being recognized as integral in solving the world’s biodiversity crisis. What part did it play in COP15?