Environment

Clean commute

Canada's largest cities are paving the way for more eco-conscious commuting choices

- 3352 words

- 14 minutes

Travel

Exploring the vibrant green labyrinth of Montreal’s ruelles vertes

Mark Twain once gazed out over Montreal’s rooftops in awe, struck by the array of sky-piercing church steeples that dwarfed all but the city’s eponymous mountain. Indeed, in 1881 the francophone and anglophone churches at the centre of the city’s communities were numerous enough for Twain to proclaim Montreal “the city of a hundred steeples.” But 140 years later, visitors’ eyes are drawn a little lower. Tucked away in shadowy spaces behind colourful rows of turreted sixplexes and spiralling staircases, you will find the new hearts of Montreal’s eclectic communities. Les Ruelles Vertes.

Montreal possesses a vibrant and diverse air, each of its boroughs displaying a distinct and lively character. Whether it’s the cafes, restaurants and markets of Little Italy, the techni-coloured facades and Parisian boulangeries of the Plateau, or the ramshackle charms of Verdun, Montrealers have long found ways to put the unique flavour of their communities on display. As any local will tell you, it’s the summer when the city truly comes alive. But venture off the bustling boulevards and peek around the shaded, leafy corners of the city’s back alleys and you’re in for a welcome surprise: A labyrinth of greenery, a euphony of live music, or perhaps an exhibition of colourful murals.

The Ruelles Vertes project is a community-led initiative that has been steadily growing since the 90s. There are now 455 green alleys in total, according to Eve Lortie-Fornier, director of Éco-Quartier, the group responsible for the Ruelles Vertes project. They are spread throughout the city in 15 boroughs, each providing a window into their neighbourhood’s unique spirit.

“It’s really starting with the citizens,” says Lortie-Fornier. “If they want to have a green alley, they have to create a committee. So they’re really taking care of the alley, they are cleaning it and then they are deciding what they want to do. Some have cinemas outside for the kids, some of them paint murals on the walls.”

With summer around the corner and some COVID-19 restrictions still in effect, the green alleys are a perfect way to explore Montreal. Whether by bike or on foot, there is something for everyone.

“It’s a great way to spend time and see the true colour of the city,” says Lortie-Fornier. “When you’re travelling you want to see where the people live out their lives. If you walk in front of a house the door is probably closed, but when you go into the alleys you will see how Montrealers really live.”

Take a stroll through history

These aren’t your regular back alleys. They’re back alleys with a history. In the mid-to-late 1800s, around the time of Twain’s famous visit to Montreal, the city was still going through the process of being transferred between the French and British regimes — and that included the city planners.

Before 1850, alleyways or ruelles didn’t exist in quite the same way, with access to the hearts of residential blocks provided by a porte-cochère. British urban-planning, however, included wide, open alleyways with street access — and so, Montreal’s back alleys were born.

The alleys have been through several life cycles — first as lanes for workers to transport goods such as ice and coal, then as garbage collection points. By 1950, automobiles ruled Montreal. As a result, many alleyways were paved over for car access, giving them a more familiar look. They were becoming an eye sore, however, and newer developments abandoned the concept completely. It wasn’t until Mayor Jean Drapeau came along in the 80s that the renaissance of the ruelles began. He laid the groundwork for the Ruelles Vertes project, developing parks in 58 alleyways. The first true green alley, however, wasn’t developed until 1995, in the trendy and artistic Le Plateau-Mont-Royal borough. It still stands today, nestled between the quadrant of Napolean, Roy and Mentana street and Parc-La Fontaine Avenue.

Map: Ruelles Vertes de Montréal / Google My Maps

The heart of the community

Lortie-Fornier sees the green alleys as a way to bring the residents of a block together, in good times and bad. The shared space brings neighbours closer, making them more resilient. Whether it’s friends close by or someone to check on their kids, the alleys provide a way to connect that was previously lacking. However, they aren’t just for the residents, says Lortie-Fornier.

“Of course, the alleys are for the people living there, but they are for the people visiting too,” she says. “I think it’s a great way to be in a place with a lot of movement while exploring the city.”

The greening of the previously gloomy, concrete alleys also provides an environmental benefit, with leafy trees providing shade from the summer heat and luscious community gardens sucking carbon out of the air.

Whatever your reason for being in the city, one thing is for certain. Take a walk on the green side and you won’t forget it. Like Twain, you could find yourself in awe — and if he were to pass through the Montreal of today, he may have a slightly different nickname in mind: the city of 100 alleys.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

Canada's largest cities are paving the way for more eco-conscious commuting choices

Mapping

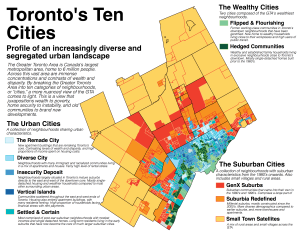

Urban geographer Liam McGuire on how he used maps to illustrate growing inequalities in Canadian cities

Travel

Alex Hutchinson goes inside the friendly rivalry between two titans of the Montreal-style bagel to figure out the secret of the doughy snack’s allure

People & Culture

The death of an unhoused Innu man inspired an innovative and compassionate street outreach during the nightly curfew in 2021