Travel

The spell of the Yukon

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

- 4210 words

- 17 minutes

Travel

The new movement building flourishing tourism hubs across Canada – one sustainable example at a time

Something weird was happening in the small mountain town of Rossland, B.C. In 2020, as the pandemic dragged on, the outdoor adventure mecca was thriving — yet few tourists were to be found. The West Kootenay community on B.C.’s famed “powder highway” is known for its hiking, biking and skiing, but even as visits plummeted, real estate was booming. And instead of closing, new businesses were opening — including the Rossberry Hill Bistro, whose menu boasts local ingredients, and the Wild Turkey Inn, a 1905 high Victorian-style heritage home that’s been painstakingly restored. You could say Rossland was undergoing its second gold rush. The first — when the discovery of rich gold deposits sparked an actual gold rush that saw Rossland become the premier mining centre of North America — peaked in 1897, with the town’s population soaring to 7,000. By 1929 it was all over. Mines unprofitable and abandoned, the number of residents plummeted to a mere 2,100. The boom had officially bust, and many businesses shuttered.

Rossland Mayor Kathy Moore can’t help but see that first gold rush as a cautionary tale. The town’s colourful history, remote location and natural beauty combine to make Rossland an enticing destination, and Moore can pinpoint exactly when she realized that only the townspeople could save Rossland from a second boom-bust cycle. It was 2007, not long after Red Mountain, the much-loved volunteer-run ski hill that the Sinixt people call kmarkn or “smooth top” had been sold to a private investment group. Within months, the group proposed developing a golf course in the hills above the town — directly atop the community’s watershed. “That got people’s attention,” Moore says. The community was told there would be no environmental risks; however, a group of local physicians soon raised concerns over the potential danger of golf course herbicides leaching into the water. “We realized we needed to decide for ourselves what we wanted,” she says.

The town came together and developed an official community plan to identify the vision, goals and objectives of citizens when it came to land use, conservation, growth, housing, transportation and recreation. It quickly became clear that locals were worried that unmanaged tourism could damage Rossland. “It sounds unfashionable, but why do we need to grow? We decided we’d rather have fewer visitors than risk changing the town’s essential character,” says Moore.

Regenerative tourism is the concept of developing travel experiences that ensure employees, businesses, communities and ecosystems can flourish.

So instead of trying to attract tourists, the town put its residents first. “We worked on the beautification of Columbia Avenue [an 1890s-era main street that harkens back to the Wild West] and brought in high-speed internet to appeal to nomadic entrepreneurs.” They also began working with Red Mountain’s owners to ensure development plans complemented the town and supported local businesses and community goals. The result? Unlike in many ski towns, homes in the new Red Mountain Village development weren’t snapped up by investors looking for a second or third property but were instead bought by people eager to become year-round residents of Rossland.

Between 2006 and 2021, Rossland’s hotel revenues more than doubled and its population grew from 3,278 to 4,140. Columbia Avenue once again emerged as a vibrant town centre — home to festivals, dozens of locally owned businesses and a newly developed heritage walking trail. Volunteer organizations thrived, with locals running the Rossland Heritage Commission, the Rossland Council for Arts and Culture and the Black Jack Ski Club — a cross-country ski area with a trail that winds through a stand of old-growth forest. Friends of the Rossland Range created trail sign- age and rebuilt eight day-use cabins on some of the area’s most scenic hiking and biking trails. And in 2019, the Rossland Lions Club opened the 100 Acre Wood Trail through a grove of old-growth trees in a forest belonging to ATCO Wood Products.

“It’s been a long time since I’ve heard anything negative about tourism,” says Moore.

And while they didn’t plan it, Rossland had stumbled on a cutting edge travel movement, one that destinations across the country are now waking up to. Billed as an antidote to the sort of extractive tourism that leaves local residents wary and the environment depleted, regenerative tourism is the concept of developing travel experiences that ensure employees, businesses, communities and ecosystems can flourish in a long-term and sustainable way, and even make things better for residents. Think of it as flipping traditional tourism on its head — instead of judging success by the number of people at hotels, the movement considers tourism in a more holistic way. The term was coined by Anna Pollock, a 45-year veteran of the tourism sector, who in 2010 founded Conscious Travel, an education and consulting business devoted to creating a better form of tourism.

Based on this model, tourism is a tool that can be used to create thriving destination communities and to regenerate and heal damaged resources. At its best, regenerative tourism should bring wealth into a community, offer good jobs, protect the local culture and play a role in rebalancing and protecting the environment. This can happen in many ways, but a major component is attracting businesses that are invested in a place for the long run, ensuring money stays in the host community and the tourism jobs being created benefit the entire community. The model takes its cues from Indigenous tourism, which is often regenerative by its very nature, playing a role in sustainability, reconciliation and cultural reclamation. The most important part of making regenerative tourism work is attracting the right guests. “Not just people who will spend money,” says Gracen Chungath, senior vice-president of destination development for Destination Canada, the Crown corporation tasked with promoting tourism in Canada, “but visitors who will be respectful and treat a host destination well.”

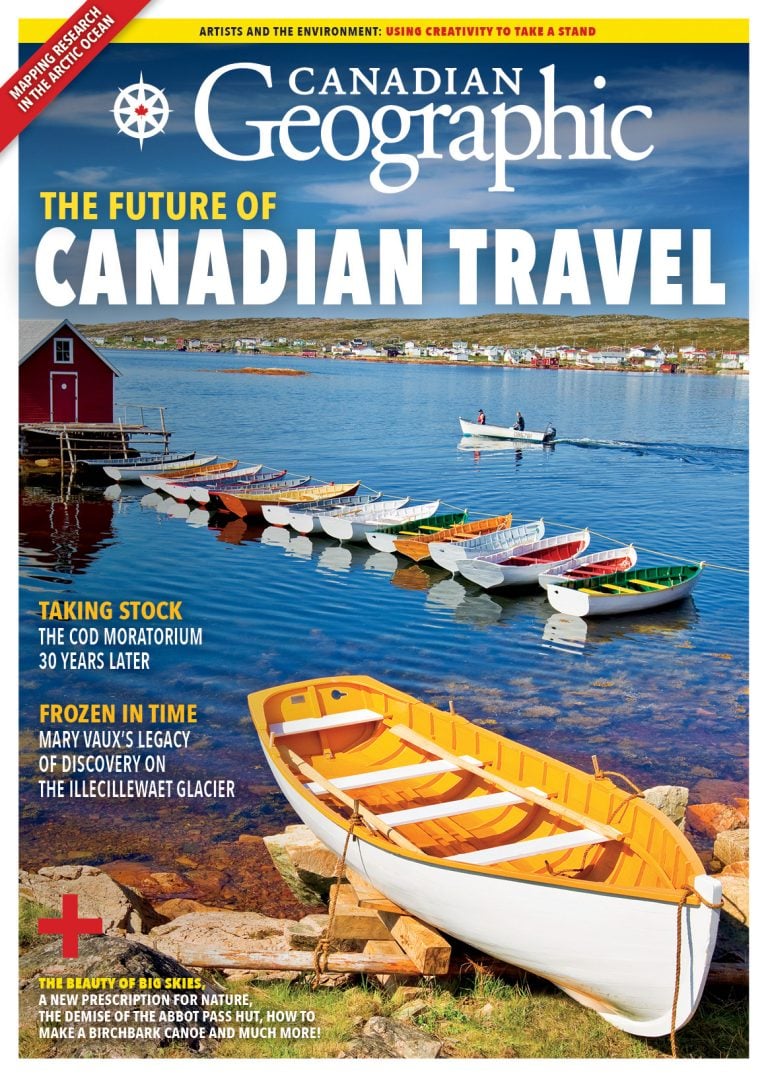

When Susan Cull graduated from high school at the turn of this century, the Fogo Island resident didn’t think she had a future on her beloved island. The cod moratorium had gutted Newfoundland’s fishing industry, the island’s lifeblood, in the early 1990s — and outport communities were dying. “There was a mass exodus from the island; it was really bleak,” recalls the now vice-president of Shorefast Operations.

Then, a stroke of genius — a spark from deep within the fading embers of Fogo Island’s own population. Zita Cobb, a high-tech millionaire who made her fortune in the Ottawa tech boom, envisioned a bold strategy to reignite her island home. The Shorefast Foundation, founded in 2004 in partnership with her brothers, Anthony and Alan Cobb, brought 400 years of culture — cod and all — into the limelight, masterfully highlighted through art and tourism. Cobb saw plenty inside the rocky coastal borders of Fogo Island with which to rebuild the community. “She asked simple, place- based questions: What do we have? What do we know? What do we love? What would we miss?” says Cull. Some of the answers — “the people, our culture and the geography” — made tourism seem like a natural fit.

The result? The 29-room Fogo Island Inn, a modern accommodation designed by Newfoundland-born architect Todd Saunders, with floor- to-ceiling windows offering views of sea and sky. And 100 per cent of the inn’s operating surpluses are rein- vested into the community. After the inn started to welcome guests, spin- off businesses began to emerge: restaurants, retail operations, artists and makers. The plan was working–and now the community’s goal was to carefully manage growth. Art has been given a central role, with art residency programs, galleries and artists taking root on the island where 10 years ago there were none. Young people began to return and the population stabilized. “There was hope. My husband and I realized we could raise our family on Fogo, the way I’d always dreamed,” says Cull.

As Fogo Island’s flame rekindled, the idea that the right kind of tourism can regenerate an entire community suddenly seemed transferable — and it wasn’t long before other destinations took notice. Shorefast launched the Community Economies Pilot, bringing together different types of communities to learn from each other. Four such communities have since been engaged by Shorefast to join with Fogo Island to collaborate and contribute to the pilot — South Vancouver Island in B.C. and Hamilton, London and Prince Edward County in Ontario. “No two places are the same — an island in Newfoundland doesn’t have the same needs as a city like Hamilton or Victoria. But it was amazing to see our similarities in the problems we’re facing. We have things to teach each other,” says Cull.

Victoria is an old hat when it comes to tourism, but it was desperately in need of an image revamp. Before the mature tourism destination could begin to reimagine its future, however, it had a major problem to solve.

“I learned that before we could get to regenerative tourism, or even sustainable tourism, we had to deal with the issue of seasonality,” says Destination Greater Victoria CEO Paul Nursey. As primarily a summer destination, Victoria was home to many tourism ventures that struggled in the off-season. Destination Greater Victoria began to focus on supporting businesses by marketing the city as a four-season destination. At that point, Nursey says “behind the curtain” innovation began taking off, with sustainability at the core.

“We have Big Wheel Burger, a locally owned, completely carbon neutral burger chain with zero waste. The Fairmont Empress, our iconic hotel, invested in their boiler system to reduce their carbon footprint. We have carbon- neutral hotels like the Laurel Point Inn. Harbour Air is piloting electric planes. Prince of Whales whale-watching is investing in research to reduce ship noise,” Nursey says. “Sustainability is part of our identity now.”

Even the city got on board, vowing to reduce community-wide emissions by 80 per cent from 2007 levels by 2050 and make the switch to 100 per cent renewable energy. And in 2021, Destination Greater Victoria achieved a carbon neutral designation from leading climate advisory services company Offsetters — the first major destination marketing organization in North America to reach this goal.

And while environmental sustainability is just one element of regenerative tourism, it can actually help support the other aspects. “Employees look to the businesses they work for to show leadership in sustainability,” says Jill Doucette, the founder of Victoria-based Synergy Enterprises, which helps guide tourism businesses toward carbon neutrality. The happy result is an influx of tourists who are committed to visiting sustainable destinations.

After years of greenwashing, which sees everything from cruises to ski holidays described as eco or ethical, travellers want to support businesses that can backup green-friendly claims. “Consumer trust is a fragile thing,” says Doucette. “Something we’re passionate about is creating transparency. Many of our clients now publish their carbon footprint.”

Victoria, like many destinations across Canada, is working toward a Biosphere sustainable tourism designation granted by the Responsible Tourism Institute in Spain. Sponsored by UNESCO, the UN Environmental Program and the European Union, the designation is aligned with the United Nations’ 17 sustainable development goals and the Paris Agreement to fight climate change adopted at COP 21. It is awarded based on a comprehensive set of sustainability measurements.

For inspiration on kickstarting a sustainable revolution, Victoria needn’t look far. Canada’s first certified Biosphere used to be what one local tourism official called “a summer party destination that attracted people who wanted to get drunk and throw beer bottles in the lake.” Now, B.C.’s Thompson Okanagan has shifted into a destination that’s thinking seven generations into the future. The process started in the early 2010s with a tourism strategy that looked at the region’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats before coming up with a 10-year tourism plan focused on sustainability.

Taking into account that “tourism isn’t sustainable if it doesn’t respect and support the communities in which [it happens],” Karen Chalmers, the managing director of Symphony Tourism Services in Kelowna, says the area’s tourism association began its “substantial story of sustainability” with steps that included developing relationships with each of the 33 Indigenous communities within the Thompson Okanagan and encouraging businesses and communities to be creative with their sustainability solutions. The ideas that followed included the creation of an “electric highway” (with easy to access charging stations); actions like those at Burrowing Owl Estate Winery, which donates 100 per cent of its tasting fees to the Burrowing Owl Conservation Society; and partnerships like those at Upside Cider, which supports local organic farmers by using their fruit in its ciders.

From there, the tourism association created the 7 Affirmations Pledge, a tourist oath designed “to support the people who call the Thompson Okanagan home, and to enrich those who travel in this region.” By having visitors promise to discover the soul of a place in its history, choose to buy locally and act as guardians of the land, air and water, the Thompson Okanagan is attracting a new kind of tourist.

It wasn’t long ago that tour buses were showing up to disgorge their passengers into Wiikwemkoong First Nation on Manitoulin Island in Northern Ontario. “We didn’t invite them, and it felt invasive,” says Luke Wassegijig, the tourism manager at Wikwemikong Tourism. The First Nation — which had shied away from tourism because of its colonial roots — found themselves overrun by unwanted visitors who wandered uninvited through sacred places.

The First Nation decided that becoming involved in tourism might be a good way to safeguard their culture. They started by building their own tourist information centre to allow the community to control its own story and guide visitors to under- stand where they should — and shouldn’t — go.

“Tourism isn’t sustainable if it doesn’t respect and support the communities in which it happens.”

From there, the community consulted about the types of visitors they wanted to attract. “We needed to build infrastructure that would appeal to both the community and the kind of visitors we wanted,” Wassegijig says. Healthy active living was a priority, and so hiking trails, a fitness park and boat launches soon followed. The crown jewel was the 7,200-hectare Point Grondine Park, the first Indigenous- owned park in Canada to be designed from the ground up.

As the community worked through these infrastructure projects, they began thinking about the next phase. Out of this grew a cultural guide pro- gram: wilderness guides, who take their visitors out on the landscape by boat and by land, received training in both outdoor education and traditional knowledge.

The results were transformational for the entire community. “Guides are reclaiming our culture and teaching guests about our strong connection to the land. And the guests are genuinely interested — they want to take part in reconciliation and land-based learning,” says Wassegijig.

This idea — that First Nations should seek out guests who are interested in learning about authentic Indigenous culture — is also essential to the ethos at the Hôtel-Musée Premières Nations in Wendake, a Huron-Wendat Nation site in Quebec. The concept began with the museum, which the nation designed as a place to preserve their knowledge, territory and memories. But though tourists visited the museum, it only showed them the community’s past. The community wanted to show off their contemporary culture as well.

So the Hôtel-Musée Premières Nations was born — a 55-room boutique hotel, spa and restaurant that opened in 2009 and introduced visitors to First Nations hospitality in this region. “People had in mind what they’d seen in the movies or history books, but they didn’t know about the modern side of everything,” says Danisse Neashit, who oversees tour- ism sales development at Tourisme Wendake. The hotel gives the staff — who come from eight different nations in Quebec — the chance to share their cultures. The hotel offers a variety of cultural activities, from making a porcupine quill bracelet to visiting the longhouse, and operates a restaurant with a menu inspired by the bounty of the land. “Our chef re- creates some of the flavours of traditional gastronomy — you’ll have the taste of firewood in the veggies, and the jellies taste like the berries were just picked,” says Neashit.

The plan is working. Today, Neashit says the opportunity to work for the hotel, which is undergoing a $6.5-million expansion, adding 24 rooms, is a dream come true. “I have so much pride in my culture and wanted to share it in an authentic way. Now, more and more people from all over the world are coming here to learn about the culture of the First Nations people.”

Through regenerative tourism is a recent buzz phrase, its momentum has been growing for a few decades, spurred on by programs such as Shorefast’s Community Economies Pilot and conferences that have focused on educating communities across the country on how best to tap into their strengths, nurture connections and find sustainable ways to share what they love with visitors.

The key has been to include as many community voices as possible, often ones that haven’t been previously acknowledged.

Communities are discovering that when you create something special for the locals, tourists will also come to share in the bounty. Until recently, Richmond, B.C., was perhaps best known for its delicious Dumpling Trail and Richmond Night Market, and as the home of the Vancouver airport. Then Tourism Richmond realized the area was a secret mecca for birders, who flocked to the wetlands and seashore to look for dozens of species of migrating birds, including snow geese and trumpeter swans.

“We’re on a critical flyway, but only serious birders knew how rich the region is,” says Ceri Chong, director of destination and industry development at Tourism Richmond. From that realization, the BC Bird Trail network was born. “Once we built the basics — identifying trails, creating itineraries, hiring guides, developing information booklets and a website — non-birders became novice birders and people learned how important these areas are to our environment,” she says. After enjoying the trails, both locals and tourists spend money at nearby restaurants and hotels and participate in other local activities.

Meanwhile, in Montreal, the ruelles vertes (green alleys) movement first began in 1995. The idea was for locals to transform their alleyways into gar- dens, play areas or gathering spots to counter the urban heat-island effect, improve air quality, provide bird habitat and increase plant biodiversity. In 2019, there were 350 green alleyways, and by the end of the first year of the pandemic, there were more than 450. Somewhere along the way, tourists discovered the secret gardens and began exploring them through bike tours by Spade & Palacio or on walking tours detailed on blogs, apps and YouTube videos. From there, pop-up concerts and other locally driven events started to occur, and the alleys grew into something much more valuable than local green spaces.

Regenerative tourism is the idea that we protect, maintain and future-proof what we already have, whether it’s a historic main street, a traditional outport, a forest of old-growth trees or a culture that’s thrived since time immemorial. The process is sometimes complex, but ultimately rewarding. Success requires cooperation throughout a community — bringing together people who don’t normally have a say in tourism — to create a destination that is good for all.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the July/August 2022 Issue

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

Travel

Jill Doucette, founder and CEO of Synergy Enterprises, shares insights on new trends in the tourism industry and why there’s reason to be optimistic about a sustainable future for travel

Travel

Un nouveau mouvement créateur de pôles touristiques florissants dans tout le Canada – la durabilité, un exemple à la fois

People & Culture

The history behind the Dundas name change and how Canadians are reckoning with place name changes across the country — from streets to provinces