People & Culture

On thin ice: Who “owns” the Arctic?

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

- 4353 words

- 18 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Exploration

Two hundred years before Franklin and 300 years before Amundsen, a daring Dane came closer to finding the Northwest Passage than anyone had before

Jens Munk is not a prominent name in Canadian history books. In fact, most Canadians have likely never heard of the Danish explorer who in 1619 undertook an expedition in search of the Northwest Passage and ended up overwintering near what is now Churchill, Man. Yet remarkably, some 200 years before the famous Franklin expeditions got underway in 1825, and three centuries before Norwegian Roald Amundsen succeeded in traversing the Northwest Passage, Jens Munk broke through the icy Davis Strait, found Frobisher Bay and spent a brutal winter on the shores of Hudson Bay.

In the early 1600s, European countries anxious to share in the vast riches that were being generated by trade with the Orient were on a quest for a northwestern sea route to China and India. Just nine years after Henry Hudson’s failed Arctic expedition on behalf of the Dutch East India Company, King Christian IV of Denmark-Norway commissioned a Danish expedition. King Christian not only wanted to establish a new trade route to the Orient to expand Danish industry and trade, but he also hoped to establish a Danish colony in North America.

Christian chose Jens Munk, one of the best seamen in the Danish kingdom, to captain the frigate Enhiörningen (the Unicorn), and the Lamprenen (the Lamprey), a smaller vessel called a sloop. These two ships, the frigate with a crew of 48 and the sloop with a crew of 16, were among the best of the King’s exploring ships. By the spring of 1619, both were stocked with Danish trade goods in preparation for a dangerous journey across the North Atlantic.

Munk was the obvious choice to lead the expedition; he had previously sailed the ice-filled Barents Sea on an unsuccessful mission to find a northeast passage, ending up at Kildin, a small outpost near what is today Murmansk, Russia. Munk also spoke Portuguese, English, Dutch and had knowledge of other languages, including an ability to write Latin. The King knew Munk had the respect of the men who had sailed with him in the past. But who was this daring Dane?

Jens Munk was born on June 3, 1579 on his father’s estate near the modern town of Arendal in southern Norway. Munk’s family had something of a checkered past. His grandfather Niels, once considered nobility, had been stripped of his noble rank for having an improper relationship with a bondwoman. Jens himself was born out of wedlock to his father Erik and the daughter of a barber from Elsinore. In 1585, Erik was convicted of fraud and using royal property for his own gain. His lands were seized, and he was sent to prison in Dragsholm Castle, near Kalundborg, Denmark.

Now an outcast in her community, with no way of supporting her small family, Jens’ mother Ann sent her son to Aalborg, Denmark, where he lived with his father’s sister and her husband. At 12 years of age, Jens returned to Norway and signed on as a crew member on a skipper for a voyage to England and Portugal. In 1592, when he was still only 13 years old, he worked his passage to Brazil as cabin-boy on a trading vessel. Jens lived in Brazil until 1598; when he returned to Denmark, he learned his father had committed suicide while in prison.

In 1611, Munk joined the Danish navy and served as a naval officer for more than five years before entering the whaling industry in 1616. When it came time to choose a leader for the Danish Arctic expedition, Munk’s complicated family history was clearly not held against him by King Christian. As historian W.A. Kenyon writes, “Munk was chosen, in all probability, because he was the most highly qualified man in the Danish navy. He was brave, experienced in Arctic navigation, versatile, and trustworthy – fine qualities in any leader – and an excellent choice for the task that lay ahead.”

One of the things that sets Munk’s expedition apart from others of the time is how much we know about it today thanks to the captain’s handwritten diary. Munk left a detailed record of the journey, the setbacks and the harsh winter spent near the mouth of the Churchill River. His descriptions of the geography they encountered, the mistakes they made and the provisions and clothing they should have had to survive the winter would provide a valuable roadmap for those that followed.

On the day the expedition was to depart, a worship service was held in Christian IV’s newly built church, the Holmens Kirke in Copenhagen, to bless the 63-member crew, Captain Munk and their families. There were some colourful, even odd characters amongst the crew, including chaplain Rasmus Jensen, described as a “sorry figure, unwashed, with a week’s growth of stubble on his chin, running eyes, and a wheezing voice.” The chaplain was on board to care for the crew, but was also likely part of the King’s plan to establish a settlement in newly discovered lands. In one of the perhaps unintended legacies of the Munk expedition, Rasmus Jensen became the first Lutheran pastor to set foot on Canadian soil and the first of any faith to hold a worship service in Western Canada.

The ships left Copenhagen on May 9, 1619; one year later, Munk and a handful of remaining men were trapped by ice in Hudson Bay, having endured a winter of darkness, hunger and hopelessness.

After leaving Denmark in May, Munk was in position to see the western shore of Davis Strait in early July. However, ice and fog prevented him from approaching land. When the weather cleared, he sailed into Frobisher Bay, thinking it was the Hudson Strait. He followed the shore of the strait between ice and land, and at a place he called ‘Rinsund,’ according to his journal, he anchored and went ashore to talk to the natives and to shoot reindeer. After leaving Rinsund, Munk was caught in the ice for six days before getting to a small cove he called ‘Haresund,’ the modern location of which is not precisely known. By mid-August, he was sailing again towards Hudson Bay. Unfortunately, the English pilots on the ship miscalculated the route, which meant the expedition didn’t get to the ‘Big Sea’ (Hudson Bay) until September of 1619. By that time, the approaching winter made further progress impossible. It was also too late to make a return voyage to Denmark, so Munk and his crew were forced to overwinter in the Unicorn along the frozen shores of the bay.

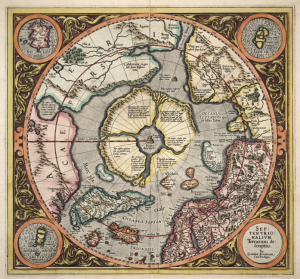

Munk’s account of the bay is the first to treat the inland sea as a whole, and his map is the first on which the whole of the bay is depicted. While wintering at what is now the town of Churchill, Man., Munk recorded a number of scientific observations and opinions. He wrote about the migrations of birds and an eclipse of the moon, and described the icebergs he had seen in the straits he had navigated.

But the Danes were totally unprepared for the full, unmitigated fury of an Arctic winter. Their clothes were insufficient for the cold, their food supply ran short, and malnutrition and illness ravaged their bodies. Munk’s diary became a litany of the dead and dying as man after man succumbed to scurvy, trichinosis (from eating tainted meat) and exposure.

By mid-February, only seven men remained healthy enough to fetch wood and water and complete everyday shipboard tasks.

“When Laurids Bergen, one of the seamen died on 5 February, I sent an urgent message to the surgeon requesting in God’s name that he assist us with whatever medicine or good advice he might have to offer. Because he himself was very ill and weak at the time, I suggested that he might like to tell me what medicine or remedy would be used for the benefit of the crew. And again he replied, as he had earlier, that without the assistance of God he was helpless.”

Passages such as the one above are interspersed with more hopeful notes about catching ptarmigan and the occasional hare to eat, but even these are tempered by Munk’s dismay that most of the surviving men “could not eat the meat because their mouths were so swollen and inflamed with scurvy.”

On June 4, 1620, believing himself to be the only expedition member still living, Munk, in a weakened, malnourished state and demoralized from the deaths of his crew, wrote something of a last will and testament:

“In as much as I no longer have any hope of living in this world I request for the sake of God if any Christian people should happen to come upon this place that they bury my poor body in the ground, along with the others who may be found here, receiving their reward from God in Heaven. And further that this my journal may be forwarded to my gracious Lord King (every word found herein is altogether truthful) in order that my poor wife and children may obtain some benefit from my great distress and miserable death. Herewith farewell to all the world and my soul into the hands of the Almighty.”

Imagine Munk’s surprise when, four days later, he opened his eyes, realized he was still alive, ventured outside into the spring sunshine, and found he was not alone. “To my astonishment, I saw two men who were still on shore. I thought they too had died long ago.”

As spring finally came to the shores of Hudson Bay, Munk and the two surviving crew members were able to gather berries, hunt and fish. With their strength somewhat restored, they set about readying the Lamprey, a vessel meant to be sailed with a crew of 16, for a return voyage to Denmark with a crew of only three.

After a long 68 days at sea, sailing out of Hudson Bay and into Hudson Strait, east and south through Davis Strait, around the south of Greenland, and back across the North Atlantic, the three men sighted the coast of Norway on September 20, 1620. Munk’s bad luck continued once they landed in Bergen: the local governor, Knud Gyldenstjerne, was an old rival of Munk’s and had Munk thrown in jail after one of his crewmen caused a drunken scene in a parlour. However, rumours that Munk was alive had reached King Christian in Denmark, and the King himself demanded Munk’s release. On December 20, 1620, Jens Munk was finally home in Denmark.

Munk didn’t exactly receive a hero’s welcome. In his absence his wife had taken a lover and the King initially demanded that Munk return to North America to fetch the Unicorn. The King also wanted Munk to take a group of settlers back to North America with him to establish a Danish colony. However, no potential settlers could be recruited to make the voyage, so the idea was abandoned. Ultimately, despite the unsuccessful search for the Northwest Passage, the tragedy of the expedition, and the failure to launch a second expedition, Christian was impressed enough with Munk to make him a captain in the royal fleet.

In 1625, Denmark entered the Thirty Years’ War, and Munk took part in battles at Fehmarn and at Kieler Förde in March and April 1628. Munk died on June 26, 1628, probably from wounds sustained in battle. A French scientist, Isaac de la Peyrère, who served as a legate at the French embassy in Copenhagen, told a rather more imaginative story about the explorer’s end: he claimed Munk died from injuries inflicted by King Christian, who attacked him with a stick during a dispute. If true, it is a sad end indeed to the partnership between the ambitious King and the seafarer who almost conquered the Northwest Passage. Munk is buried at St. Nikolai Lutheran Church in Copenhagen.

Nearly 100 years after Munk and his two surviving crewmen left Churchill, British explorer James Knight arrived at the harbour where the ships had been trapped. Knight found the unburied bones of many of the Danish crew, consistent with Munk’s testimony in his diary that by the end of the winter, the surviving expedition members had been too sick and weak to even bury their dead.

In 1964, a couple of cannon balls and a piece of iron were unearthed during an expedition by the writer Thorkild Hansen to the mouth of the Churchill River, which is believed to be where Munk’s Nova Dania (New Denmark) was located. Hansen wrote about the Munk expedition and the discovery of the remains of the Unicorn in the tidal flats of the Churchill River in a book entitled The Way to Hudson Bay: The Life and Times of Jens Munk. The location near Churchill was discovered in part due to old maps and the information in Munk’s diary.

In 1991, the Manitoba Heritage Council installed a commemorative plaque for the Jens Munk Expedition at the Prince of Wales Fort National Historic Site in Churchill. Munk’s expedition was also the inspiration for several place names in the Churchill region. Gordon Point, today a popular spot for polar bear safaris, is named for William Gordon, who was one of the English pilots on the Munk expedition, and Styggy Creek near the Golf Balls Historic Site is named for Morvitz Styggy, a Munk lieutenant and crew member.

Munk’s journal, Navigatio Septentrionalis – Navigating the Northern Waters, was published for the first time in Latin in 1624, while he was still alive. Today, you can find the original, well-preserved, 400-year-old diary in the Royal Library in Copenhagen.

The journal was translated into English in 1897 by C.C.A. Gosch and published by the Hakluyt Society, London with the title Danish Arctic Expeditions 1605 –1620. The journal was later edited by W.A. Kenyon and published in Canada in 1980 by the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) as The Journal of Jens Munk 1619-1620.

This year, the Federation of Danish Associations in Canada and its Jens Munk Commemorative Steering Committee received permission from the ROM to digitize and re-publish the Munk journal in honour of the 400th anniversary of the expedition. Throughout 2019, Danish Canadians have a number of events planned in Manitoba and at the Danish Canadian Museum in Dickson, Alta. to commemorate the historic expedition.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

People & Culture

Explorer Adam Shoalts, who completed his monumental 4,000-kilometre journey on September 6, speaks to Canadian Geographic about an expedition that calls to mind the likes of Vilhjalmur Stefansson and Joseph Tyrrell

Exploration

A behind-the-scenes look at the adventures and discoveries of the passionate explorers funded by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society

People & Culture

In this essay, noted geologist and geophysicist Fred Roots explores the significance of the symbolic point at the top of the world. He submitted it to Canadian Geographic just before his death in October 2016 at age 93.