Throughout the ongoing search for Franklin –which occupied nearly a hundred and sixty years before Parks Canada took up the cause in 2008 – there were numerous Inuit figures, without whose testimony the search might never have met with success. Most of them were not ‘historians’ in the modern sense, but in keeping the old stories alive, and helping searchers understand them, they were vital links in the chain of knowledge. Among them, two figures loom particularly large, William Ouligbuck and Tookoolito, who worked with John Rae and Charles Francis Hall respectively.

Ouligbuck was a gifted translator; not only was he fluent in Inuktiut, Cree, and Chipewyan, but by Rae’s account he spoke English “more correctly than one half of the lower classes in England and Scotland.” The accuracy of his translations was vouched for again and again, and Rae stoutly defended him, even in the face of withering (though groundless) criticism from Charles Dickens. It was the testimony he translated – about the last of Franklin’s men, including the fact that some of them had resorted to cannibalism – that first brought eyewitness Inuit accounts to the world at large.

Tookoolito, or “Hannah” as she was known to the Cumberland Sound whalers, worked with her husband Ebeierbing (“Joe”) on all three of Charles Francis Hall’s northern ventures. Having been taken to England as a teenager by the whaling captain John Bowlby, she had taken tea with Queen Victoria, and Hall was startled, at their first meeting, by her good English and western manners, and she was a natural translator. She never wavered in her commitment to Hall’s project of locating Franklin survivors, and came to share his enthusiasm for the quest. The vast amount of material in Hall’s field notebooks forms the core of the Inuit testimony that guided the discovery of HMS “Erebus.”

There were, of course, numerous other Inuit through the years who continued to relay their traditions to Franklin searchers, among them In-nook-poo-zhee-jook (Rae and Hall), Puhtoorak (Frederick Schwatka), and Qaqortingneq (Knud Rasmussen). And, even as recently as the 1990’s, Inuit elders whos spoke with historian Dorothy Eber showed that, at least in part, these traditions had survived right into the present day: Fred Analok, Moses Koihok, Mabel Angulalik and Tommy Anguttitauruq all told her stories that can be traced to early testimony.

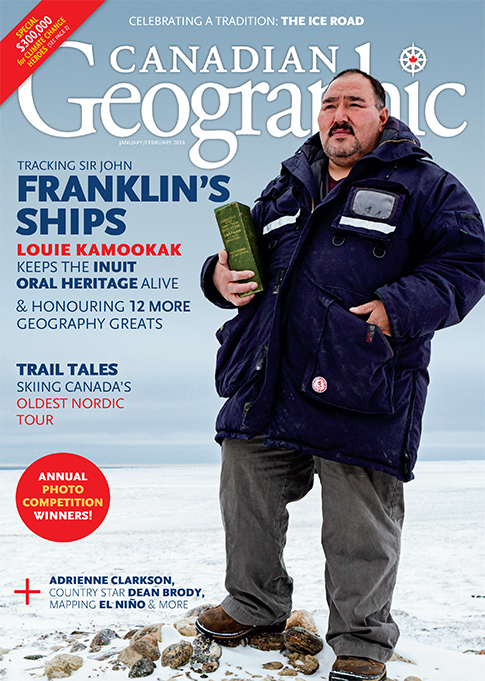

As for Louie Kamookak, he is unique in that he has taken on not only the oral traditions of his family and people, but also studied the written records of explorers and earlier testimony. In that sense, you could say that he’s actually the first Inuk historian to tackle the Franklin mystery.