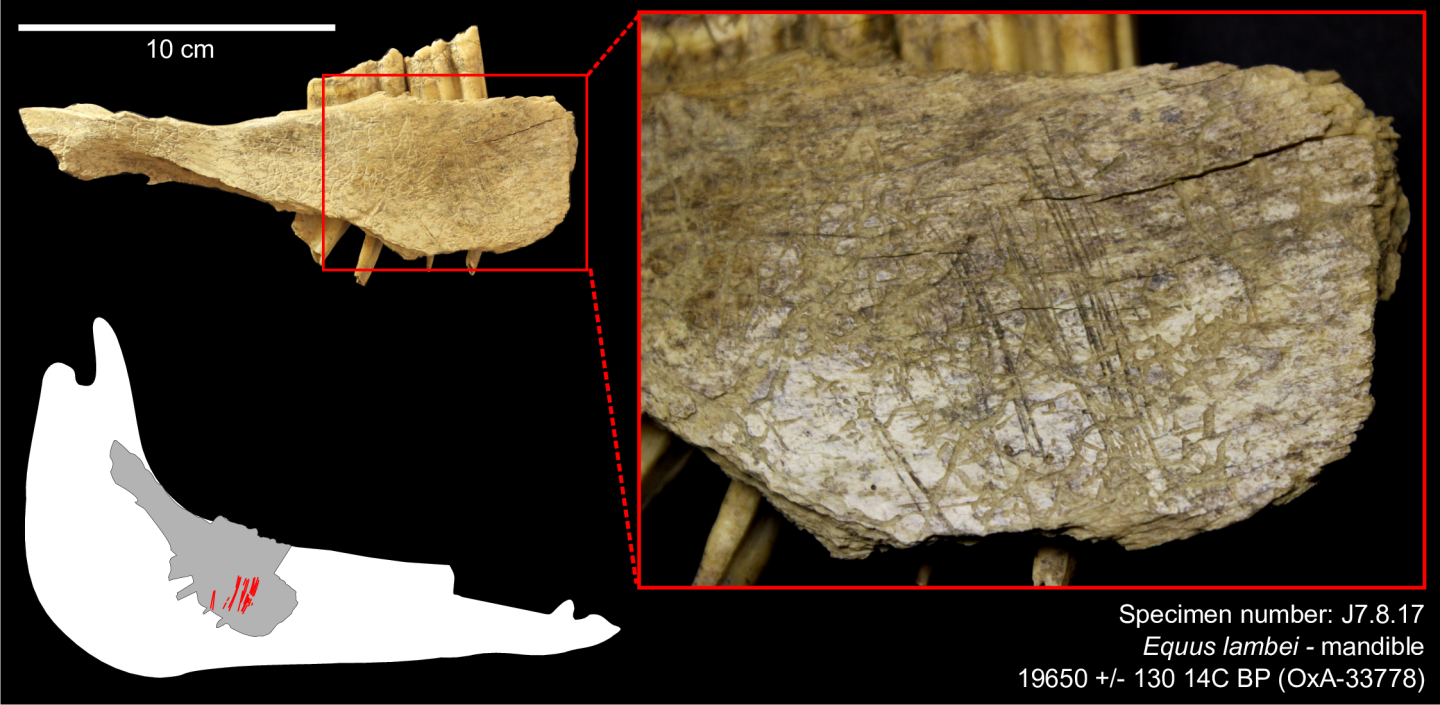

The horse mandible from Cave II is dated to 23,000 to 24,000 years ago. The bone surface is a bit weathered and altered by root etching but the cut marks are well preserved and are associated with the removal of the tongue using a stone tool. (Photo: Plos One/journals.plos.org/)

On the Bluefish Caves

The site was excavated from 1977 to 1987 under the direction of Dr. Jacques Cinq-Mars with the help of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation. The collection is stored at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que. My research consists of identifying the mammal bone specimens (i.e. the taxa and the anatomic element), then identifying the agents responsible for the modification of the bone surface, such as trampling, carnivore gnawing, human activity, etc. This has been a long and meticulous study that took me two years. There are about 36,000 bone specimens from Caves I and II. Many specimens are fragmented and quite small, but they all deserve a few minutes of examination under a microscope.

On what the recent radiocarbon dating proves

Our radiocarbon dating was made on bone bearing evidence of human activity, while previous dating was made on bones that didn’t always bear such evidence. We decided to date a horse mandible which happened to offer the oldest date (23,000 to 24,000 BP). There is also a humerus bone and a metatarsal bone from the same species, as well as metacarpal and coxal bone fragments from caribou. We also dated a bone shaft fragment that may belong to wapiti. Radiocarbon dating allows us to date the human presence at the site and it actually proves that people were in the Yukon as early as 24,000 BP.

On why that’s significant

Until now, we thought that people arrived in North America about 14,000 BP. Before that date, there was a glacial period called the Last Glacial Maximum. It was hard to imagine humans living in Alaska and the Yukon during that period. But our results show that people were there during the Last Glacial Maximum and remained genetically and geographically isolated in the Beringia region between 24,000 and 15,000 BP before continuing to migrate into North and South America.