People & Culture

RCGS names Jill Heinerth as Explorer-in-Residence

Cave diver Jill Heinerth is one of Canada’s greatest explorers and a world-leading technical diver. She's also the RCGS's very first Explorer-in-Residence.

- 443 words

- 2 minutes

Exploration

In her book, Into the Planet: My Life as a Cave Diver, world-renowned cave diver and inaugural RCGS Explorer-in-Residence Jill Heinerth reflects on what set her on her path

On Friday, Feb. 5, 1971, the PA system at Munden Park Public School in Mississauga, Ont., reverberated with a special announcement. The school principal requested staff and students assemble in the library — to watch television!

As school had started that day, two men were donning spacesuits for a walk on the moon that lasted more than five hours. At about 4 a.m., Apollo 14 had landed in the moon’s Fra Mauro crater, the intended landing site of the aborted Apollo 13 mission of 1970.

Our teachers seemed a bit nervous as we watched the walk, perhaps because of a fresh awareness of the risks astronauts face. Alan Shepard seemed relaxed as he filmed Edgar Mitchell bunny-hopping down the Antares lunar module’s ladder with a Maurer 16-mm movie camera. The crew planted the American flag, off-loaded an experiments package and even hit a couple of golf balls before the day was through. It was the third time astronauts had been on the moon. I was mesmerized.

“Mom, Dad, I want to be an astronaut!” I declared over dinner that evening. They were accustomed to my earnest goalsetting at mealtime. I had already expressed interest in people I had seen on TV, whether it was Jacques Cousteau, Marlin Perkins of Wild Kingdom fame or “the most trusted man in America,” CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite.

It was a transformational time, when we had no Canadian space program, no women astronauts and few positive female role models on TV. A new sitcom, All in the Family, was considered edgy, but perhaps not as influential as the forward-looking show Maude — boasting an outspoken, politically liberal female main character — that would soon spin-off from it.

The ladies in my young life took care of their families. My mother, a graduate of Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont., left behind teaching to pursue her most important role in life — to ensure the solid upbringing of three children.

On Sunday evenings, my siblings and I were permitted to eat dinner in our den in front of the TV. It was always a special occasion to watch Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom and The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau. These programs made me aware of the world, and beyond.

That same year, I saw the Canadian IMAX film North of Superior at the new Cinesphere at Toronto’s Ontario Place. Seated in a comfortable reclined seat, I soared over Ontario’s landscapes in an entirely new way, as an aerial camera panned over the province’s endless pristine wilderness.

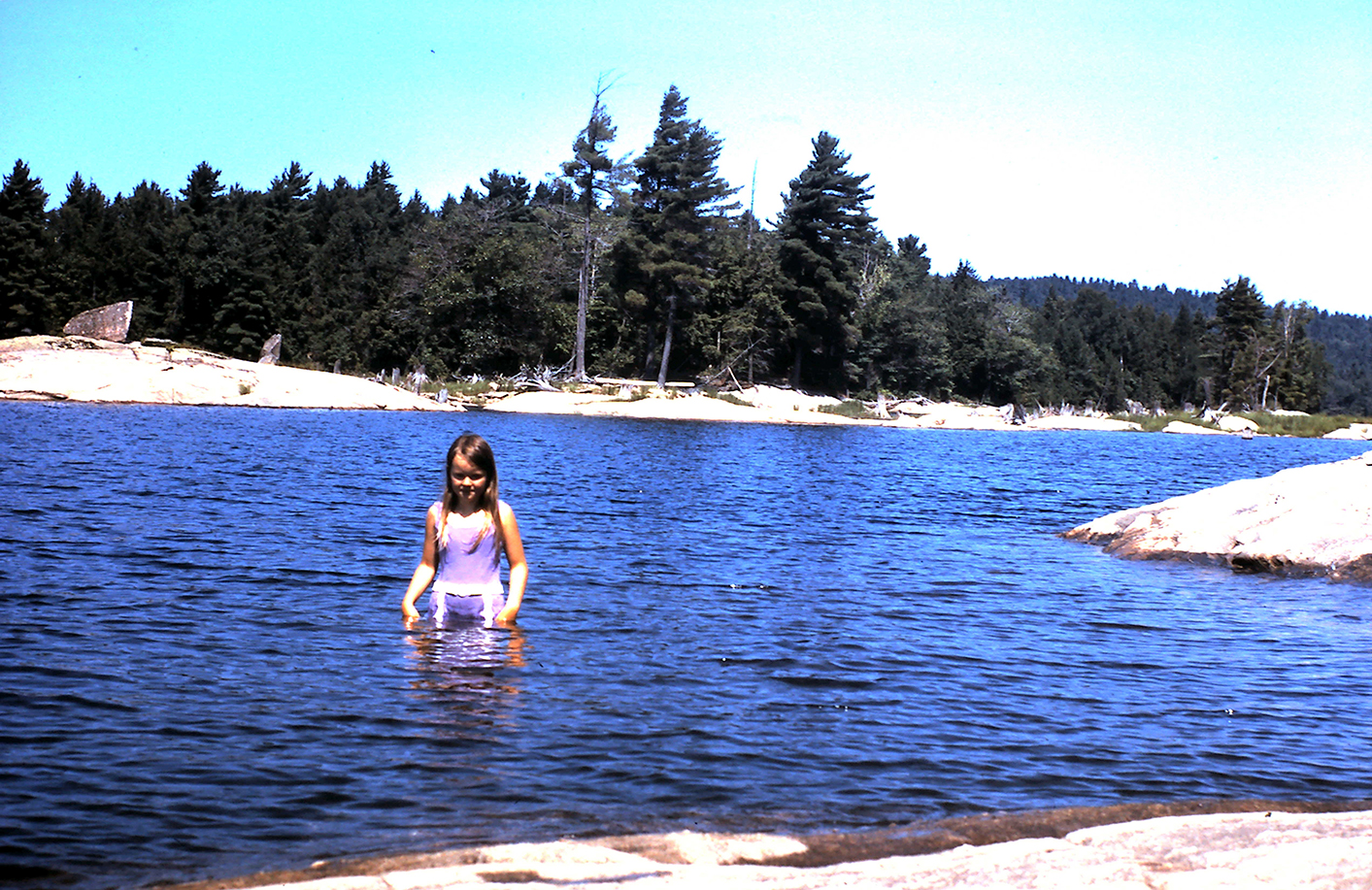

Meanwhile, our family spent weekends combing through rocky crevasses along Ontario’s Bruce Trail or paddling our canoe in remote lakes in the Muskoka region. As a young girl, I felt like anything I set my mind to was possible. I wanted to be an explorer.

We are all born as explorers, putting everything in our mouths from our earliest days to discover pleasure or elicit disgust. We learn boundaries through experiences that are either exhilarating or leave us injured. We soak up new information like a sponge and, by doing so, find the fundamental interests and experiences that give us the most satisfaction.

For me, the joy was found outdoors, hiking with my Brownie pack, swimming in Lake Ontario and digging fossilized crinoids out of a local construction site. Opportunities to explore were everywhere. Sharing knowledge was encouraged around my family’s dinner table and in classes as early as kindergarten. Show and tell was one of my favourite activities. An unusual rock, the shed skin of a snake or a jar of “The Amazing Sea Monkeys” (brine shrimp), were props that launched my love of public speaking.

I read books about the Bermuda Triangle and the Group of Seven, and built a model that showed how earthquakes worked. I mixed a love of science and geography with my artistic talents, never quite landing on a specialization other than a love of learning.

When it came time to choose a direction for my university studies, I was stymied. With good grades, I could go anywhere. But what would I study? Should I follow my dad and become an engineer? Or could I take a program in the newly emerging subject area of environmental science?

Instead, I chose to do what my paternal grandparents had done and become a commercial artist. I imagined a career in advertising that would involve collaboration, problem-solving and working with a diverse client base in varied disciplines. I envisioned travel and learning as a foundational part of my new existence. While I worked hard in my program in visual communications and design at Toronto’s York University, I also signed up for a class in something I had always wanted to do: scuba diving.

I first tried my new hobby in Fathom Five National Marine Park, a newly designated national marine sanctuary near Tobermory, Ont. Descending beneath the glassy surface of Lake Huron to explore a hidden grotto in the limestone cliffs of the Niagara Escarpment changed everything for me. When I looked up to see the light beaming through a portal in the rock, I felt like I was exploring the womb of Mother Earth.

Growing up, I thought the age of exploration was over. The highest mountains had been climbed, the deepest trenches of the ocean had been reached and men had walked on the moon. What was left? But floating in the neutral buoyancy of a new world, I realized that I could be an explorer, too. The childlike, carefree joy of discovery was reignited. I would find a way to combine my creative talents with my love of learning and the underwater world.

Through volunteering and collaboration with scientists, I eventually rose to the top of my sport, exploring caves and deep underwater vistas as a documentarian/storyteller and the hands and eyes of scientists who weren’t able to travel to the dark subaquatic corners of our planet.

In underwater caves, I work with biologists discovering new species, physicists tracking climate change, and hydrogeologists examining our limited freshwater reserves. Probing the underground pathways of the planet, I document grisly sources of pollution, the roots of life inside Antarctic icebergs, and ancient skeletal remains of Mayans sacrificed in the cenotes of the Yucatan Peninsula. Deep inside our planet, and with just my camera, I share mysteries locked away in places that are less visited than the moon’s Fra Mauro crater.

So how does a young woman today pursue a life of discovery and exploration? The opportunity lies at the intersection of volunteering, research and active outdoor experiences. We hit the geographic jackpot growing up in Canada. Whether you seek discovery opportunities in our vast landscape or choose to look inward to explore the microscopic geography of DNA, nanotechnologies or quantum particles, there are boundless opportunities for pioneering research. It just takes stepping over the threshold of darkness to bear witness as your eyes adjust to the dim light of a new opportunity.

For me, that life of discovery has led to the ultimate reward of serving as The Royal Canadian Geographical Society’s first Explorer-in-Residence. And with my honorary role, I intend to continue serving as the role model I wish I had met when I was 10. Today, there are no bounds for women explorers. We can swim through submerged caves under a ceiling of solid rock or smash through the glass ceiling of gender bias to explore where no person has been before.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

People & Culture

Cave diver Jill Heinerth is one of Canada’s greatest explorers and a world-leading technical diver. She's also the RCGS's very first Explorer-in-Residence.

People & Culture

The RCGS Explorer-in-Residence discusses the underwater world of cave diving, the risks involved, pushing boundaries and more

People & Culture

The eco-explorer discusses his new role with the Society and the importance of sustainable travel

Exploration

A behind-the-scenes look at the adventures and discoveries of the passionate explorers funded by the Royal Canadian Geographical Society