Travel

The spell of the Yukon

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

- 4210 words

- 17 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

Three miners pause to smoke their pipes before returning to drilling dynamite holes deep into asbestos-laden rock in Nicolet, Que. In the Eastern Townships, a woman cards asbestos fibres, preparing the material to be woven into clothing. In a “cobbing” room at Thetford Mines, rows of “bright and healthy looking French-Canadian girls” wearing floral patterns and swinging hammers smile as they crack apart asbestos rock.

These are a few of the images printed in Canadian Geographical Journal‘s feature stories “Asbestos — ‘Pierre à Coton’ ” (October 1930) and “Fibres of gold” (March 1938). Both are sweeping and celebratory accounts of a burgeoning industry built on what was then considered a miraculous, indestructible substance with powerful peace- and wartime applications.

Centred primarily south and east of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, the asbestos business was at the time worth more than $10 million per year in exports alone (about $150 million today), and B. Marcuse, president of the Canadian Asbestos Company in 1930, predicted that “in the next hundred years [it would] make still greater strides and become one of the most important industries.”

A long-awaited ban

While it didn’t quite last another century, asbestos was a staple of the Canadian construction industry for longer than it should have been. Today, the federal government announced a comprehensive ban on the use, export and import of all asbestos products, an expanded building registry and other measures — legislation long demanded by public health and labour groups. Although Canada’s last asbestos mine closed in 2011, the mineral has continued to be imported in products such as brake linings and pads, asbestos cement and even its raw form.

This, despite the fact that medical researchers in Canada, the United States and Europe have been adding to a mountain of peer-reviewed studies connecting asbestos exposure to chronic inflammation and scarring in the lungs (a condition called asbestosis) and a slew of fatal cancers since the 1930s.

And there’s no shortage of evidence that corporations knew about the dangers of asbestos but neglected to warn labourers and the public. The claim that workplace hazards could be “eliminated” by “planning, modern methods, and safety education,” was repeated for decades; in the 1938 issue, T.R. Elliott wrote, “Every employee of the mine, as well as those in mill and factory, is required to take an X-Ray examination at least once a year, just as a precaution against possible dust diseases. The incidence of tuberculosis among workmen, remarkably enough, is less than among the general population.”

Meanwhile, early studies were already finding that one in four workers was suffering from asbestosis but that symptoms of the condition and other harmful effects of asbestos exposure might not manifest for years. As recently as July 2016, the Globe and Mail reported that experts at the Occupational Cancer Research Centre at Cancer Care Ontario estimate that asbestos exposure is still to blame for at least 2,000 cancer cases in Canada every year — most of them fatal.

The European Union enacted a total ban on asbestos in 2005, and the substance is already prohibited in more than 20 other nations. Environmental lawyer David R. Boyd, a professor in resource and environmental management at B.C.’s Simon Fraser University, says Canada lagged behind so many other wealthy, developed countries in part because of “the untenable belief that [asbestos] can be used safely.”

Given what we know about this mineral today, it’s natural that we’d cringe upon seeing a photo of Danville, Que., locals from the ’30s with this caption: “Mrs. Gifford, as a girl, used to pass the hilltop on the way to school and pluck strands of pure asbestos fibre for chewing gum.” But it’s part of a fascinating snapshot of a time before “asbestos” was a bad word, and when the colossal economic promise of the small-town Quebec industry dwarfed the inconvenient findings of a still small body of medical studies.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

Wildlife

Salmon runs are failing and grizzlies seem to be on the move in the islands between mainland B.C. and northern Vancouver Island. What’s going on in the Broughton Archipelago?

Science & Tech

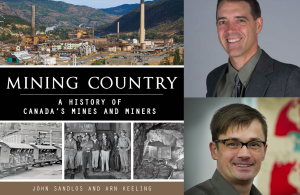

An exclusive excerpt from a new book, Mining Country, which promises to document in detail for the first time an industry critical to Canada’s past, present and future

History

Dora Nipp, CEO of the Multicultural History Society of Ontario, reflects on the importance of chronicling migrant, ethnic and Indigenous stories as an essential means to understanding Canada in the 20th century and beyond