Travel

The spell of the Yukon

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

- 4210 words

- 17 minutes

Science & Tech

An exclusive excerpt from a new book, Mining Country, which promises to document in detail for the first time an industry critical to Canada’s past, present and future

Among the multitude of human economic activities, few inspire such romantic and nostalgic accounts as the discovery and development of mines. From legends of El Dorado to the prospectors of the Klondike, mining (especially, but not exclusively, for gold) has long fired the imagination with tales of instant riches dug from the earth. Exploration for minerals, in this positive view, lured humans to far reaches of Earth, expanding geographical knowledge and driving the expansion of the European powers. Many still celebrate the industry as a nation-building enterprise, promoting frontier mining as the best opportunity for development in otherwise “empty” territories. In older mining towns, many of which have suffered the shock of mine closure, residents still look longingly to the excitement of the early boom days and the esprit de corps among the families who inhabited frontier mining communities. For its boosters, mining is not only a source of considerable local wealth, but has provided the lion’s share of the critical materials that sustain cities and enable our modern, technology-driven lifestyles.

Mining also inspires intense feelings from a largely opposing viewpoint. The industry’s detractors have long linked mining with the unbridled exploitation of both people and the environment. According to this darker view of mining history, prospectors and geologists did not merely conduct a courageous search for valuable minerals, but served as agents of empire who laid the groundwork for the violent conquest and dispossession of distant lands. Even the most legendary mines of the “New World” (such as Potosí in Bolivia, source of Spanish imperial wealth beginning in the 16th century) are sullied by their association with slavery and death. Throughout much of the industry’s long history, critics have noted that mining work is notoriously dangerous, workers have been subject to low wages and other forms of exploitation, and boom-bust mining economies have become synonymous with resource exhaustion and community collapse.

From the earliest days of the industry, observers have condemned the environmental impacts of mining, such as the construction of massive tailings ponds, the production of waste-rock piles, the pollution of waterways and the emission of toxic smelter smoke.

Much popular mining history reflects the boosterish side of these polarized views. In North America especially, mining history has tended to be of the “sourdoughs and gold pans” variety: stories that are intensely local and generally celebratory. These histories often provide valuable records of the communities founded by mining and the colourful people associated with developing the mining frontier. Yet rarely do such accounts look beyond local developments to consider how these communities fit into the wider pattern of mining as an industry. Nor do they reckon with the products (and byproducts) of mining — what historian William Cronon called the “paths out of town” — that connected remote mines and settlements to industrial technologies and consumers in distant cities, and that linked mining activities to their “downstream” ecological impacts.

In our book, Mining Country: A History of Canada’s Mines and Miners, we explore both sides of the historical debate over Canadian mining history without embracing either extreme. Our work acknowledges that mineral products are undoubtedly central to the economies and lifestyles of our contemporary world, and mining holds a prominent — if curiously neglected — place in the history of Canadian colonization and development. At the same time, we acknowledge that these benefits (if indeed they are seen as such) have also come with great costs: the dispossession of Indigenous groups from their land base, the maiming and death of mine labourers and the degradation of the environment. The multiple mining stories included in this book do not add up to a simple homage or denunciation of mining, but they do indicate the industry’s generally neglected importance to the history of Canada and the legacies of this history for mining communities and regions today.

Mining Country introduces readers to major themes and developments in the history of Canadian mining, from Indigenous trade in minerals to the large-scale, integrated industrial developments of the late 20th century. The search for valuable minerals, we argue, played a key role in the expansion of European settlement and economic activity in northern North America and the interactions between colonists and Indigenous peoples. By the early 20th century, mining emerged as the sole resource industry with a significant presence in every region of Canada, from east to west coasts to the northern territories. Over the century since, mining became a significant contributor to Canada’s resource economy, and Canadian companies rose to become some of the world’s most prominent mining firms. Yet aside from a lively body of locally focused popular histories and some scholarly case studies, there is no general synthesis of mining history in Canada. Although some (largely celebratory) chronicles of mineral discoveries and major developments appeared in the mid-20th century, a general narrative of Canadian mining history remained, until now, unwritten.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe

Science & Tech

The mining industry is actively looking towards new frontiers in mining

People & Culture

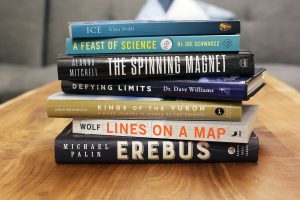

Memoirs, a graphic novel and the biography of a famous ship are among Canadian Geographic's choices for the 14 best books of the year