Science & Tech

How the Homeward Bound expedition program is empowering women in science

As a biologist and photographer, I had long hoped to visit Antarctica — but this journey was much more than a travel dream fulfilled

- 1126 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Antarctica has the world’s coldest temperatures, worst weather and most isolated living conditions. That can make life stressful for the people who spend the long polar winter at research stations there, sapping morale and affecting their ability to do their jobs, which is why University of British Columbia psychologist Peter Suedfeld is looking for ways to reduce that stress.

Stress comes in a variety of flavours at an Antarctic station. There’s the fear of illness or injury in a place far from hospital, where high winds, low temperatures, remoteness and darkness make winter medical evacuations risky. There’s the monotony of eating, sleeping, working and spending leisure time in one place with the same people for months on end.

“If you’re stuck there with somebody you really can’t stand,” Suedfeld says, “too bad. You’re stuck with them. And if you’re missing somebody who’s far away, too bad. You’re stuck without them.” What’s more, Antarctic stations can be dull places to live. They’re designed to minimize construction cost, rather than keep people amused, interested and comfortable, and extreme weather can make stepping outside for a change of scenery difficult, dangerous or impossible.

Under these conditions, says Suedfeld, some people thrive by developing a sense of solidarity and teamwork. Others may become depressed and change their behaviour. One station cook began serving unpalatable meals to his crewmates after a love affair with a co-worker went sour, until the group revolted and frightened him back into line. In an extreme case at Russia’s Vostok station in 1959, a scientist became unhinged after losing a game of chess, and murdered his opponent with an axe. Chess was subsequently banned at Russian Antarctic stations.

“We’re hoping to find improved ways of identifying when people are under higher stress, to monitor their adjustment to the Antarctic environment,” says Suedfeld, who, with his European colleagues, is looking for clues in the recorded speech of Antarctic workers.

The Concordia station, operated by France and Italy, is one of his research sites. “It’s very isolated,” he explains. “And it’s located in a place with really bad weather and low atmospheric oxygen because of high altitude. There are about a dozen people there in the winter.” Once a week, staff read and record a standardized short story and an oral diary, which they share with researchers via the Internet. “My colleagues in Europe measure characteristics of speech,” says Suedfeld, “things like speech rate, voice pitch and volume and number of hesitations, that might reveal the level of stress.”

Suedfeld will be analyzing the contents of the diaries: “I’ll look at comments about things such as mood and the other people, personal feelings about being at the station, homesickness. We’re also doing a deeper analysis of how the cognitive process is going in terms of thinking flexibly, finding solutions to problems and motivation. Other research has shown that some people become less capable of solving problems: they can’t remember what they need to remember, they behave impulsively and so on.”

Suedfeld’s goal is to use his findings to suggest changes to Antarctic winter station procedures, environments and crew interactions, to reduce stress and make life more pleasant and comfortable.

Virtual reality technology — Star Trek style — could eventually be part of the solution, suggests Suedfeld. “We may be heading for a total immersive, virtual environment, like the Holodeck on the fictional USS Enterprise, but obviously not that sophisticated. Realistic computer-generated environments could reduce stress by allowing you to step into a totally different world that’s varied and exciting.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

As a biologist and photographer, I had long hoped to visit Antarctica — but this journey was much more than a travel dream fulfilled

Science & Tech

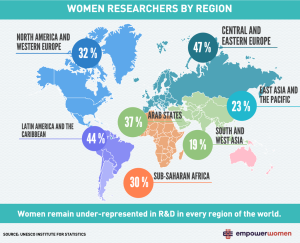

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

Environment

Ten years after the release of her seminal book Sea Sick, Alanna Mitchell again plumbs the depths of the latest research on the health of the world’s oceans — and comes up gasping

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)