Science & Tech

How the Homeward Bound expedition program is empowering women in science

As a biologist and photographer, I had long hoped to visit Antarctica — but this journey was much more than a travel dream fulfilled

- 1126 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

In the shadow of the massive West Antarctic Ice Sheet, tiny creatures harbour clues to ancient environmental changes at the southern end of the world — and to potential future changes around the planet.

Ian Hogg, an ecologist with Polar Knowledge Canada who lives in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, works with a team of scientists from New Zealand and the United States to comb unexplored areas of Antarctica for information about present and past polar ecosystems.

While his colleagues focus on the microscopic inhabitants of the thin Antarctic soil, such as nematodes (roundworms) and eight-legged tardigrades, Hogg studies the giants of this ecosystem: springtails. A dozen of these six-legged arthropods would fit comfortably on your fingernail, but in the Lilliputian world of Antarctic land animals, says Hogg, “they’re the functional equivalent of elephants.”

Elsewhere in the world (the snow fleas that appear on the late-winter snow in Canada are a variety of springtail), these animals can drift from place to place on river or ocean currents. But in Antarctica, says Hogg, they stay put: “There are areas with no open shorelines and very little in the way of running water, so in many cases springtail populations have been stuck right where they are for the last five million years.”

“When we look at their genetics,” he explains, “we can see how long different springtail populations have been separated from each other.” That provides the scientists with information about how long particular regions of Antarctica have been isolated and, as it is ice that separates the springtails, the behaviour of ice sheets.

The team’s research supports geological evidence that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet — which is two kilometres thick and nearly the size of Nunavut — collapsed about five million years ago. This made it possible for some springtail populations to mix, and their gene pools expanded. The ice sheet eventually returned, and within the last million years has collapsed and returned again, mixing and separating springtail populations each time.

Glaciologists suggest that the ice sheet, which has been losing mass in recent decades because of the warming climate, may collapse again. And this terrestrial environment, where the springtail is king, grants ecologists a rare, uncluttered view of how an ecosystem operates. “Compared to the Arctic, with its higher biodiversity and many varieties of animals large and small,” Hogg says, “the Antarctic systems are simple, with very few parts. That allows us to understand how they work — and by learning about their histories, we can see how they might respond to change in the future. Then we can take that information and apply it to more complex systems elsewhere on Earth.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Science & Tech

As a biologist and photographer, I had long hoped to visit Antarctica — but this journey was much more than a travel dream fulfilled

Science & Tech

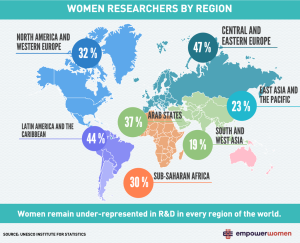

From Roberta Bondar to Harriet Brooks, Canada has more than its fair share of women scientists to be proud of. However women are still a minority in the STEM fields

Environment

Ten years after the release of her seminal book Sea Sick, Alanna Mitchell again plumbs the depths of the latest research on the health of the world’s oceans — and comes up gasping

Science & Tech

As geotracking technology on our smartphones becomes ever more sophisticated, we’re just beginning to grasps its capabilities (and possible pitfalls)