Environment

The meaning of ice

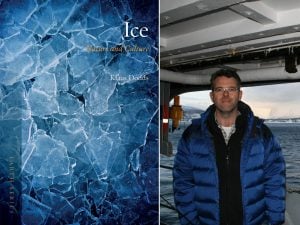

In his new book, Klaus Dodds delves into the fascinating natural and cultural history of ice

- 1293 words

- 6 minutes

Science & Tech

The ice-covered archipelago of Svalbard, located high above the Arctic Circle, is home to thousands of polar bears—in fact, there are more polar bears than people! But beyond the splendour of Svalbard’s wilderness, the archipelago also has a rich history of exploration, hunting, scientific research, and industrial development that has shaped its people and landscape.

Sunniva Sorby and Hilde Fålun Strøm are following in the footsteps of Arctic adventurers like Wanny Woldstad, the first female trapper on Svalbard, to overwinter in a remote hunter’s cabin as part of their Hearts in the Ice project. Over the course of nine months, Strøm and Sorby will be gathering data for various scientific organizations to research the effects of climate change on the Arctic.

People venture to Svalbard from all corners of the Earth, drawn by its natural beauty as much as by its economic opportunities. Those that catch the “polar bug” make it their home and stay for the strong sense of community and access to the great outdoors. However, Svalbard is not a place where you can trace back lineage from generation to generation. It has more of a transient atmosphere, popular among young men and women as a destination for work and research. More than half of Svalbard’s population is between the ages of 25 to 49.

Today, there are 2,667 people living on Svalbard, most of them residing in the largest urban area, Longyearbyen. The town provides such community services as schools and daycares, museums and libraries, churches, police and fire stations, and even a university—the University Centre in Svalbard, which is the northernmost institution of higher learning.

However, some services are limited in what they can offer due to the remoteness of Svalbard. For example, although there is a medical centre in Longyearbyen, it’s rare for women to give birth on the island. Women are encouraged to travel to mainland Norway approximately one month before their due date to give birth. This is also true for major surgeries. Additionally, due to Svalbard’s ground being permanently frozen year-round, people can’t be buried on the island.

Coal mining led to the establishment of Svalbard’s permanent settlements. It is believed that whalers first discovered coal as early as in the 17th century. Successful commercial mining on a large scale began in 1906 with American entrepreneur John Munroe Longyear, who visited Svalbard on holiday, learned about the potential of rich coal deposits, and established the Arctic Coal Company. Longyearbyen, meaning “Longyear city,” is named in his honour. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, coal mining was a profitable industry for Svalbard and all other activities revolved around it. However, in recent decades, coal has been in decline and many of Svalbard’s coal mines have been shut down, with only two mines remaining operational.

Svalbard’s unique natural landscape has also made it an important location for research, drawing scientists from various countries and diverse fields of study. Geology and biology are two major disciplines on Svalbard. The archipelago of Svalbard is one of the only places on Earth where rocks from almost every geological period can be found. Among these rock layers, researchers have excavated perfectly preserved fossils, some dating back 60 million years. The Arctic is also particularly vulnerable to climate change, and the effects of global warming can be studied and observed in the receding glaciers across Svalbard. Research and conservation are key pillars of the Svalbard scientific community. The Global Seed Vault, nicknamed the “Doomsday Vault,” is one example of a research project that has gained global significance by safeguarding and preserving more than 5,000 plant species from around the world.

Today, tourism dominates Svalbard’s economy. Tourists from all over the world visit Svalbard for a chance to spot polar bears, get up close and personal with glaciers, hike Svalbard’s rocky terrain, and experience the northern lights. About 65 per cent of Svalbard is protected—there are seven national parks, six nature reserves, and 15 bird sanctuaries. There are countless ways for visitors to explore Svalbard’s wild landscapes, from cruises and kayaks to snowmobiles and dog sleds. Organized tours are the norm in Svalbard due to the high concentration of polar bears. Tour guides always travel with flare guns and rifles as a precaution in case of a polar bear encounter. If tourists need a break from the great outdoors, they can also learn about Svalbard’s cultural heritage through its museums, art galleries, and coal mine tours.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

In his new book, Klaus Dodds delves into the fascinating natural and cultural history of ice

Environment

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?

Exploration

She's also combining her knowledge and skills to uncover the secrets of climate change