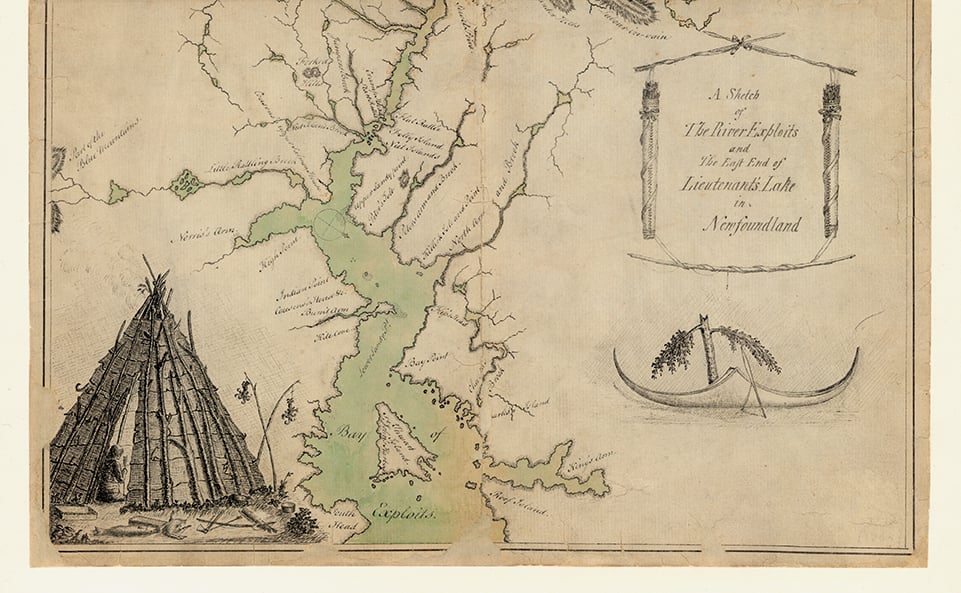

The map also shows two squares (B), which Cartwright annotated “square house, firmly built.” The walls of these larger dwellings were insulated with caribou skin to protect against the elements. One of these sits on the shores of what is labelled Lieutenant’s Lake (known today as Red Indian Lake) and the other is a little upstream at “Little Rattle.”

One of the most interesting features on the map is a series of wavy lines interspersed with dots (C), which indicates “deer foils.” These extended fences were designed to obstruct the fall migration routes of the caribou Beothuk hunted for food and skins during the annual caribou drive. To construct them, they would cut down a tree such that it fell in a diagonal line to the next tree along, and was still attached at the stump. This next tree would be similarly felled and so too the one after that until there was a natural zig-zag fence, filled in with branches, that the caribou herd couldn’t cross.

If there were no trees, the Beothuk were “at no loss,” wrote Cartwright. “For their knowledge of the use of sewels supplies the deficiency.” Sewels (D) were like scarecrows, “made by tying a tassel of birch rind, formed like the wing of a paper kite, to the small end of a slight stick.” The birch rind was hung in such a way “to play with every breath of wind. Thus it is sure to catch the eye of the deer, and make them shun the place where it stands.”

These maps, recorded by a white man’s hand, are an imperfect record of how Beothuk lived. But they are part of the fragmented story of a people that are no longer here to tell it.

*With files from Isabelle Charron, Early Cartography Archivist, Library and Archives Canada