Travel

The spell of the Yukon

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

- 4210 words

- 17 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

During the 1970s and 1980s, Sir Christopher Ondaatje led something of a double life. At work, he was well known as a crack investment analyst whose boutique firm, Loewen Ondaatje McCutcheon, earned millions for its clients. Away from the canyons of Bay Street, however, Ondaatje — who in November received The Royal Canadian Geographical Society’s Gold Medal, its most prestigious award — yearned for something more. He began reading voraciously about the exploits of the legendary British explorer Sir Richard Burton. By 1988, Ondaatje had decided to extract himself from the rat race, and in his words, he “chucked” his career.

“If you study their writings, their claims are different,” Ondaatje says. “If you do what I have done, which is follow the Burton-Speke journey, the significance is that what you read and what they have written and what they claim aren’t necessarily the whole truth.”

In 1996, accompanied by four Tanzanian guides, Ondaatje embarked on a roughly 100-day, 10,000-kilometre voyage by Land Rover, following Burton and Speke’s route up the Nile to their ultimate discovery of a vast body of fresh water that would be dubbed Lake Victoria. Burton, Ondaatje explains, stopped there, declaring it the source of the Nile. But the lake is not spring-fed, and Ondaatje, like Speke, pressed on, passing Murchison Falls (also known as Kabalega Falls) and making his way toward Lake Albert, the smaller of the two “reservoirs” feeding the Nile and first identified, as Ondaatje points out, by Herodotus more than 2,000 years earlier. “The Nile,” he says, “flows out of Albert, through the desert and on to the Mediterranean. Herodotus, in my opinion, was closer to the truth.”

The aim of that expedition, described in Ondaatje’s 1998 book Journey to the Source of the Nile, was to test the claims of the Victorian explorers against his own experiences in the same challenging terrain. “What Sir Christopher has done is revisit important exploration sites and expose them to a very bright light,” observes Society president John Geiger. He points out that Ondaatje has received the Gold Medal for both his own work and his patronage of the discipline of geography. “He’s an immensely important figure globally.”

Ondaatje’s latest book, The Last Colonial: Curious Adventures & Stories from a Vanishing World, is a collection of intriguing and offbeat outtakes from his journeys and other experiences, as well as short essays on figures like Ernest Hemingway and Burton himself. Published in 2011, the volume also revisits one of Ondaatje’s favourite literary motifs: the leopard.

At 78, Ondaatje not only continues to write but also remains peripatetic and intensely inquisitive. He explains that he still relishes an opportunity to explore the most ancient regions of the Middle East, many of which are inaccessible due to civil unrest. But Ondaatje is determined because, in his view, seeing is believing. “You can’t change history. Do the journey, open your eyes. The more you know, the more you will discover.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Travel

An insider’s account of the modern-day gold rush

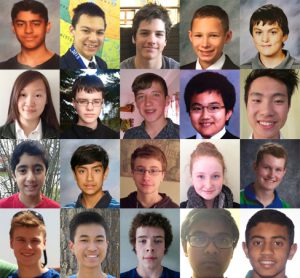

Kids

The Canadian Geographic Challenge, now in its 20th anniversary year, will bring 20 young…

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

In celebration of its 90th year, the RCGS handed out awards to a diverse and star-studded roster of honourees