(Photo: Sarah McNair-Landry)

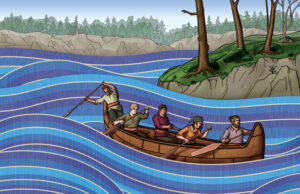

“It was a way of experiencing living history and putting ourselves in the shoes of the people who would have migrated before,” says Erik Boomer, a member of the expedition. “It really helped us respect and gain more understanding for the people who lived this way for 365 days a year.”

Fellow team member Eric McNair-Landry says this route would have been the “central highway” for people to travel along many years ago. “A lot of the time, people go on expeditions to go where people haven’t been before. We were attempting to do the opposite.”

Along the way, the team came across signs of past voyagers, including tent rings, piles of stones, and inukshuks. “I was surprised to see just how many artifacts we saw along the way and how useful they were to us,” says team member Katherine Breen, adding that the team used inukshuks to figure out the best portage routes or where the largest rapids were in a river. “We saw a lot of evidence of the fact the route had been well-travelled in the past.”

In addition to travelling in the footsteps of others, they also chose to use the traditions of the past by building their own Inuit-style kayaks for the journey.

“I thought they worked really well,” says team member Sarah McNair-Landry. “Compared to plastic boats, they were faster, if not better than the store-bought sea kayaks.”

Made of cedar and oak, the kayaks took around 200 hours to build. “We were pretty terrified they might fall apart on the expedition,” says Eric McNair-Landry, who had the longest kayak of the group at just under six metres. But the kayaks all held up well.

The team isn’t planning on abandoning their kayak-building skills anytime soon. “We would love to teach sea kayaking to communities up north, and show how to build (kayaks) and how to paddle them,” says Sarah McNair-Landry. The team hopes to inspire others and renew the tradition of kayak building that use to be prevalent in the region.

To learn more about the expeditions program, visit the RCGS website.