Environment

Inside the fight to protect the Arctic’s “Water Heart”

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

- 1693 words

- 7 minutes

History

Long before an amateur prospector struck it rich near Cobalt Lake in northern Ontario, local Indigenous nations mined and traded silver. It’s time to set the record straight on the “discovery” of Canada’s immense resource wealth.

The story of Canada’s frontier expansion into the North is a long litany of booster tales and romantic legends. Even today, the Canadian business press regularly laud the myth of the capitalist in a canoe, the rough-and-tumble prospector with the relentless drive to find the “next big discovery.” The mining town of Cobalt, Ontario, played a huge role in the development of this nationalist mythology. The wealth of the mines at Cobalt dwarfed the riches of the Klondike and changed the trajectory of development in both Ontario and Canada. And so it is worth considering the genesis tale that was told of the discovery of silver near Cobalt Lake in Northern Ontario in the summer of 1903.

According to the legend, railway worker Fredrick Larose was working his blacksmith forge when he was interrupted by a pesky fox. Frustrated, Larose threw his hammer at the creature; it missed but broke off a chunk of pure silver. The entertaining story was told in barrooms and major financial houses around the world, but the reality was that there was no fox, and the discovery wasn’t accidental. Larose found silver because he was a dedicated amateur prospector. He tried to tell journalists what really happened, but no one was interested. The story of the hammer and fox quickly became the preferred version, to sell the image of a land so rich that a person could become a millionaire almost by accident.

The myth also erased any Indigenous claim to the silver fields. The image of a white man stumbling over such immense wealth sent a clear message that riches were waiting to be taken. Canadian mining mythology has taken for granted the toxic settler myth of terra nullius — the dubious colonial claim that the theft of Indigenous land was justified because the original people were failing to “use” it according to European laws and custom.

In truth, there was a complex continental trade in Cobalt silver dating back thousands of years. Ceremonial panpipes made from Cobalt silver have been found in burial mounds in Ohio, Georgia, and Mississippi. Silver jewellery has been uncovered in archeological digs in New York State. Nuggets of pure Cobalt silver were carefully placed in Michigan burial sites. Some of these burial mounds, known as the Hopewell sites, are massive earthworks representing ingenious human endeavours that rival the construction of the great Egyptian pyramids.

Just how far back the Indigenous trade in northern minerals goes is hard to determine. Mining in Cobalt has a two-thousand-year-old history. Copper mining in the neighbouring northern great lakes has been dated back to six thousand years. So how did these silver trading networks work? Some archeologists believe the Hopewell people came north on spiritual quests to dig out the silver at Cobalt and neighbouring Gowganda. But it is more likely that local Indigenous nations mined these deposits and then traded the silver to southern nations. If this is the case, they would have taken the silver out through their trading centre at the narrows of Lake Temiskaming (twenty kilometres from Cobalt), a place the Algonquin called Obadjiwan (meeting place). From Obadjiwan, they would have portaged the silver through a series of rapids, and then into the Ottawa River system.

When white fur traders first came north in the 1600s, they met the Indigenous people at Obadjiwan, where they established a fur trading post in the shadow of the rich silver fields. However, neither the white traders nor the clergy had any knowledge of the enormous silver wealth in the overlooking hills. When the Hudson Bay fort overcharged the Indigenous hunters for guns and bullets, the hunters simply went into the bush and fashioned bullets from pure silver. They never told the fort’s factor of the rich silver deposits that lay in the hills nearby. So why this silence? Anson Gard, who chronicled the Cobalt silver rush, wrote that the Indigenous people were aware of the presence of the silver veins, but they believed that great misfortune would befall them if the white men knew.

We find a similar code of silence among the Ojibwa who mined copper along the northern Great Lakes. For accounts of the relationship between the Indigenous peoples and the metal resources of the North, we can look to Traditional Knowledge. The Ojibwa story of Nanabijou serves as a cautionary tale against sharing the secrets of mineral wealth. Nanabijou was a giant who protected the Indigenous people of the northern boreal forest. Nanabijou revealed the secrets of a rich silver mine to the Ojibwa, but warned that they must never share this information. Despite their best efforts, the white men learned of the location of the mine at Silver Islet on Lake Superior. They came with their dynamite and shaft-sinking machines, and Nanabijou was turned to stone, becoming the famous Sleeping Giant in the harbour of Thunder Bay. The Ojibwa lost their guardian and were left exposed to the destructive influx of white men.

A year after the Silver Islet Mine was established in 1868, the Hudson’s Bay Company relinquished control of their vast trading territories across the North in a deed of surrender to the newly established country of Canada. This opened the region to a flood of railway workers, trappers, and prospectors, who brought with them the exploitation, alcohol, and disease that devastated the traditional economies of the northern Indigenous peoples.

The pressure was particularly hard on the Teme-Augama Anishnabai (Temagami First Nation), who lived in the region south of the Cobalt silver fields. In the 1870s, Chief Tonene attempted to negotiate with Ottawa for a land base for his people. He warned that “the white men were coming closer and closer every year and the deer and furs were becoming scarcer and scarcer . . . so that in a few more years Indians could not live by hunting alone.”

By the turn of the twentieth century, the provincial government made the decision to drive the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway (T&NO) through the heart of Tonene’s territory in order to access the area’s rich red and white pine forests. The plan was predicated on the removal of the Indigenous people from the terrain. The question of how the Temagami people would survive once they were dispossessed of their lands was not something that troubled white politicians. The policy was rooted in another toxic myth of the American and Canadian frontier — that of the Vanishing Indian. This was a belief that the fundamental racial “inferiority” of Indigenous people would ultimately lead to their extinction, allowing white settlers to move in and take their lands.

Chief Tonene realized that farming wouldn’t be sufficient to protect the land interests at Temagami from the government and the encroachment of settlers, so he moved his family farther north to keep ahead of the prospectors. In time, the white prospecting crews moved steadily towards Tonene’s new hunting grounds along the shores of Larder Lake (one hundred kilometres north of Cobalt). Tonene knew the land well and had identified where the gold traces could be found, so he obtained a prospector’s licence and staked the very first claim in the region. The Canadian Mining Journal credited Tonene with launching the 1906 Larder Lake gold rush that led to four thousand claims being staked. What the Mining Journal didn’t mention was that Tonene’s claims were jumped by white prospectors. He tried to establish his rights through the courts, but under Section 141 of the Indian Act it was illegal for Tonene to hire a lawyer.

Tonene’s stolen claims eventually led to the founding of the Kerr-Addison Mine, one of the richest gold mines in Canadian history. Tonene received nothing from the rush. He died in 1916, and the land where he was buried was later turned into a gravel pit, and then a community dump.

The fate of Tonene is a grim reminder that that the whitewashing of the Indigenous involvement in the “discovery” of Canada’s immense resource wealth was not accidental. It was part of a much larger political and social erasure of Indigenous claims to resource lands. Restoring these voices isn’t simply about correcting the historical record; it is an inherently political act.

The need to re-examine our nationalist mythology of resource wealth has taken on a new urgency in an age of burning forests and melting ice. Canadian mining, oil, gas, and pipeline projects are facing unprecedented activism, protests, and civil disobedience — in Canada and across the globe. These acts of resistance are shaking up the political and business establishment, while Canadians are learning that our past is not the simple and wholesome mythology that we were once led to believe. By disentangling the real stories of what happened in frontier settlements like Cobalt from the parochial politeness of local Canadian history, we may be able to confront the deeper issues facing our nation today on Indigenous rights, the environment, and our relationship to the precarious North. This is not simply about coexistence and mutual economic benefit. It is a question of survival.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe

People & Culture

Indigenous knowledge allowed ecosystems to thrive for millennia — and now it’s finally being recognized as integral in solving the world’s biodiversity crisis. What part did it play in COP15?

Science & Tech

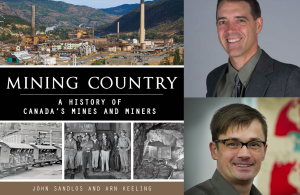

An exclusive excerpt from a new book, Mining Country, which promises to document in detail for the first time an industry critical to Canada’s past, present and future