Exploration

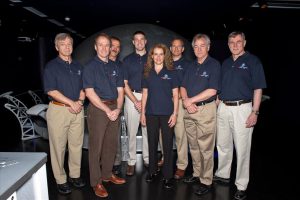

Canadian Space Agency astronaut profiles

The men and women that have become part of Canada’s space team

- 1067 words

- 5 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Science & Tech

Scientists have a new theory about the origin and composition of Mars’ moons — and it’s all thanks to a meteorite that landed on the frozen surface of a British Columbia lake nearly 19 years ago.

Until now, it was thought that the moons, Phobos and Deimos, were asteroids captured by the red planet’s gravitational pull. But a study published late last month in the Journal of Geophysical Research suggests that the moons are actually pieces of Mars itself, blown off the planet by some cataclysm early on in the formation of the solar system.

“They could in fact be fossilized remnants of the very earliest crust of Mars,” says Chris Herd, a professor of earth and atmospheric sciences at the University of Alberta and a co-author of the study.

The Martian moons share many characteristics of asteroids in the main asteroid belt of the solar system, Herd explains: they’re irregularly-shaped and pockmarked with impact craters, which suggests they’re extremely old, and they reflect very little light. Fortunately, the U of A’s meteorite collection, which Herd curates, contains samples of a similar asteroid. The so-called Tagish Lake meteorite, which exploded high in the atmosphere above B.C. and the Yukon on a January morning in 2000, originated in the asteroid belt and is estimated to be 4.55 billion years old.

The researchers compared the reflection of light from a sample of the Tagish Lake meteorite to reflection data collected by the Mars Global Surveyor Thermal Emissions Spectrometer as it passed Phobos in Mars’ orbit in 1998.

“This was a way to test how well the light off the Tagish Lake meteorite matched the light from Phobos and Deimos,” Herd says. “If they matched, it would tell us [the moons] were asteroids — but the study showed it’s not a good match.”

If Phobos and Deimos are in fact chunks of a young Mars, that would give them something in common with Earth’s own moon, which is believed to have formed 4.51 billion years ago from an impact between Earth and another Mars-sized planetary body.

A rare specimen

The Tagish Lake meteorite is “one of the crown jewels” in the U of A’s collection of around 1,800 specimens. Because it landed on a frozen lake in winter, scientists have been able to keep dozens of fragments of the meteorite cold since the moment they were collected, effectively preserving them in a pristine state.

“Contrary to popular belief, [meteorites] are not hot when they fall. The inside stays cold, and just the outside gets flash heated,” Herd says.

In the case of the Tagish Lake meteorite, that cold core has been found to contain organic compounds such as naphthalene, amino acids and even long chain fatty acids — the building blocks of life, but formed in space. It’s a rare and precious opportunity to study the geological history of the solar system.

“There are many different kinds of asteroids in the belt and they have all undergone their own geologic histories, but most of the action went on at the formation of the solar system,” Herd explains. “They’re essentially the fossilized, frozen remnants of the early solar system, and then sometimes we’re lucky enough to have a meteorite.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Exploration

The men and women that have become part of Canada’s space team

Exploration

A conversation with Canadian astronaut David Saint-Jacques, who is getting ready to travel to the International Space Station

Exploration

The significant CSA events since Alouette’s launch

Science & Tech

For scientists and northern lights rubberneckers, 2013 promises to be a once-in-a-decade opportunity to experience the sun’s magnetic power at its height.