History

Royal Canadian Geographical Society CEO John Geiger gives a sneak peek of this year’s Franklin search

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

- 1638 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Exploration

Nearly two years to the day since Sir John Franklin’s sunken HMS Erebus was discovered in Nunavut’s Queen Maud Gulf, the team responsible for the find is back on the hunt, searching for HMS Terror, the second ship of the legendary ill-fated 1845 Franklin Expedition.

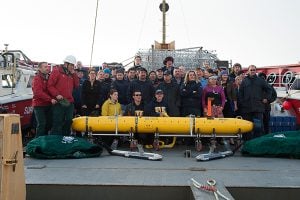

The federal government announced on Aug. 23 that Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team is expected to resume exploring Erebus and continue its search for Terror at the end of August — along with the Canadian Coast Guard’s Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the Royal Canadian Navy’s HMCS Shawinigan, personnel and equipment from the Canadian Hydrographic Service and the Arctic Research Foundation’s research vessel Martin Bergmann. The so-called “Mission Erebus and Terror 2016” will spend about nine days on this year’s reconnaissance. In 1992, the two wrecks were designated national historic sites, despite their unknown locations at the time.

“Our national historic sites tell the stories of who we are, including the history, cultures and contributions of Indigenous Peoples,” says Catherine McKenna, Minister of the Environment and Climate Change. “Mission Erebus and Terror 2016 offers a unique opportunity for historical exploration and to further the deep connections of northern communities with the story of the Franklin Expedition.”

Traditional Inuit knowledge, of course, was instrumental in locating the wreckage of Erebus in 2014. And in the lead-up to today’s announcement, renowned Franklin historians have written new works on where Terror is likely to be found, based both on historical Inuit testimony and the discovery of Erebus.

Russell A. Potter, an avid Franklin researcher and the author of the forthcoming Finding Franklin: The Untold Story of a One Hundred and Sixty-Five Year Search who also writes on the subject at his Visions of the North blog, wrote on the possible location of Terror on Aug. 18, 2016.

In “Where to look for HMS Terror,” Potter writes that “One might assume that, with one ship located and identified, it might be possible to narrow the range of sites to search for the second vessel, but that’s not necessarily the case.” He points out that since the Inuit didn’t know the names of either ship, “it takes some considerable review of the available testimony to sort out which tales refer to which ship …”

Based on various Inuit accounts, Potter points to Ogle Point, Erebus Bay and Victoria Strait as possible sites for the still-missing wreck. Potter also notes (and links to) a new piece by renowned Franklin historian David C. Woodman, which likewise ponders the possible location of Terror.

Woodman notes: “In contrast [to Erebus] the geographical clues as to the location of HMS Terror are almost non-existent. It is clear that any case setting out a search area based on testimony will not rely on specific geographical clues but must be entirely circumstantial, based on a chain of reasoning from testimony concerning other aspects of the Franklin tragedy.”

Woodman, who is perhaps as familiar with such records as any modern-day historian, then reviews the relevant records in significant detail, concluding that “The clear implication is that Terror lies, with a crushed side, in the water of Erebus Bay.” Regardless of its exact location, one detail is certain: the search for Franklin’s second lost ship is as mysterious and captivating as the hunt that led to the discovery of Erebus.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

History

Why this summer’s search for the lost ships of the Franklin Expedition will be the biggest and most advanced ever

History

Arctic historian Ken McGoogan takes an in-depth, contemporary perspective on the legacy of Sir John Franklin, offering a new explanation of the famous Northern mystery

Exploration

Archaeologists may have finally located the historic vessel that disappeared 168 years ago in Canada's north

History

Our experts dissect the debut episodes of AMC’s new series about the Franklin Expedition