Travel

How to stop a gold rush

The new movement building flourishing tourism hubs across Canada – one sustainable example at a time

- 3297 words

- 14 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

People & Culture

People were talking about the Canadian Museum for Human Rights long before it opened last year to equal amounts of fanfare and criticism. After all, it was hard not to talk about the Antoine Predock-designed structure, which has variously been described as a “bulky gyre of glass, limestone, steel and concrete,” an “impressive oddity of a building,” “the Mirabel Airport of Canadian museums,” a “prairie campfire” and, in a reference to the glass panels that cover much of its exterior, “a Darth Vaderesque cape wrapped around a Gumby-headed sasquatch.”

Here, Christina Stokes, a senior program interpreter with the museum who runs a tour of the building’s architectural features, explains some of the elements and symbolism of Canada’s newest national museum.

I usually start the tour with what the meaning of the building is. It’s quite abstract, and you don’t know exactly what it’s supposed to look like right away. The panes of glass on the outside are meant to symbolize the wings of a dove, the international symbol for peace. From the outside, a lot of people think it looks like a German [army] helmet. Some people think it looks like hands wrapped together. Kids usually say it looks like water. Before I knew what it was meant to symbolize, I thought it looked like a globe.

There are four parts to the museum, all of which are meant to be connected to the Canadian landscape. We start in “the roots,” [the blocks that help form the museum’s base] which look like a claw sticking out of the ground, and are very dark. Predock’s vision was that you’d start your journey in darkness and move to light. The roots are meant to symbolize the tall prairie grasses. Then we have “the cloud” [the panes of glass], which is meant to resemble glaciers. Then we move on to “the mountain,” [clad in Manitoba Tyndall limestone] which contains and “protects” all seven levels of the gallery spaces and is meant to bring to mind the Rocky Mountains. Finally, there’s the Tower of Hope, which is meant to evoke structures such as the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill, but when it’s lit up at night, it’s also meant to look like a beacon of light in the prairie landscape.

It was a very difficult project. They had to use 3D design and modelling to make sure all the pieces from all over the world — glass from Germany, steel and limestone from Canada, alabaster from Spain, basalt from Mongolia — all fit together when the building was constructed. The best place to see the intersection of all these pieces is in the Garden of Contemplation. A garden isn’t something you expect to see in a museum, in the middle of the gallery spaces, but it’s a space for people to discuss what they’ve seen.

Another main feature is the alabaster ramps, which have more than 900 metres of LED lights running through them. The ramps are there for accessibility, of course, but there’s symbolism in them, too. Alabaster was used in healing containers in ancient Greece, and the ramps give people a break as they walk from gallery to gallery and learn about some of the positive and less positive stories the museum tells. The ramps are also meant to look like a ribbon of light, so again, that idea of taking you from darkness to light.

400,000 The number of First Nations artifacts recovered during an archeological excavation at the site prior to construction beginning.

100 The height in metres of The Tower of Hope, equivalent to that of a 23-storey building.

24,155 The total area in square metres of the building, equivalent to the size of four Canadian football fields.

$351 million The total capital cost of the building and exhibits.

$15 The price of an adult ticket.

175,000 The number of individually cut pieces of limestone, basalt and alabaster.

1,300 The number of pieces of glass that wrap around the building.

35,000 The number of tonnes of concrete used in the building’s construction.

100,000 The number of words of original text used in the museum’s exhibits.

5,400 The amount in tonnes of steel used in the building’s construction.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the Canadian Geographic Travel: Summer 2015 Issue

Travel

The new movement building flourishing tourism hubs across Canada – one sustainable example at a time

Travel

Un nouveau mouvement créateur de pôles touristiques florissants dans tout le Canada – la durabilité, un exemple à la fois

People & Culture

The Charter goals and Indigenous people living in Canada

History

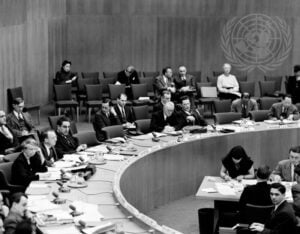

On Dec. 10, 1948, the United Nations adopted an aspirational document articulating the foundations for human rights and dignity, but who was the Canadian that helped make it possible?