(Map: Chris Brackley/Canadian Geographic. Canadian base data © Department of Natural Resources Canada. All rights reserved.)

A clear Klondike morning spreads before musher Rob Cooke as he perches on the back of his moving sled. Here, on the icy, sun-washed landscape along the Yukon River, 175 kilometres north of Whitehorse, the only sounds are Cooke’s rhythmic breathing and 52 Siberian husky paws crunching in the snow. Ten days from now, Cooke’s team of beloved dogs will pull him across the finish line of his first Yukon Quest international sled-dog race.

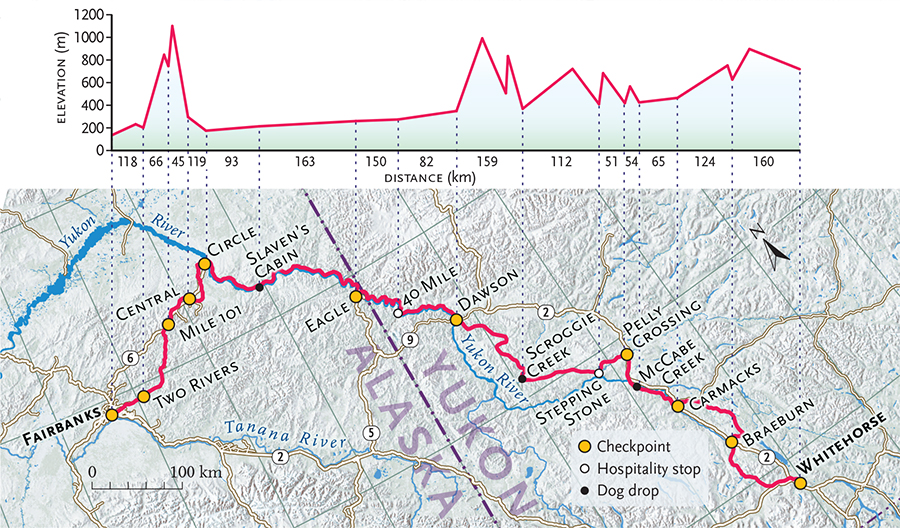

The Quest is a gruelling 1,609-kilometre test of fortitude and skill spanning a harsh landscape of frozen rivers and mountains between Whitehorse and Fairbanks, Alaska. The course, which partly follows the trail of gold rush prospectors, is a testament to international relations, with boards in Alaska and the Yukon managing the competition co-operatively since 1984. Thousands of people from all over the world make the pilgrimage to the Subarctic in early February, the coldest month of the year, to celebrate the sport of the North and experience the thrill of the start line (its location alternates between the cities annually).

For an enthusiastic few, there’s only one way to get a taste of the experience of the toughest sled-dog race in the world: suit up, spend the day on a sled, then grab a beer with a musher. The Yukon Quest journey, run by Cambridge, Ont.- based travel company Jerry Van Dyke Travel Service, offers just that — truly a one-of-a-kind adventure. The photography here, from the 2013 race, is a glimpse into the event.