People & Culture

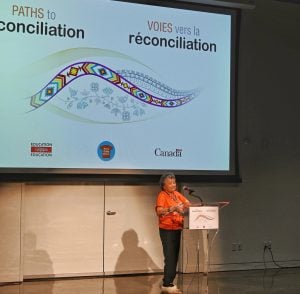

RCGS, Orange Shirt Society launch Paths to Reconciliation

New project to educate Canadian students on the impact and legacy of the residential school system announced on Orange Shirt Day

- 737 words

- 3 minutes

People & Culture

Phyllis Webstad turns her residential school experience into a powerful tool for reconciliation through Orange Shirt Day

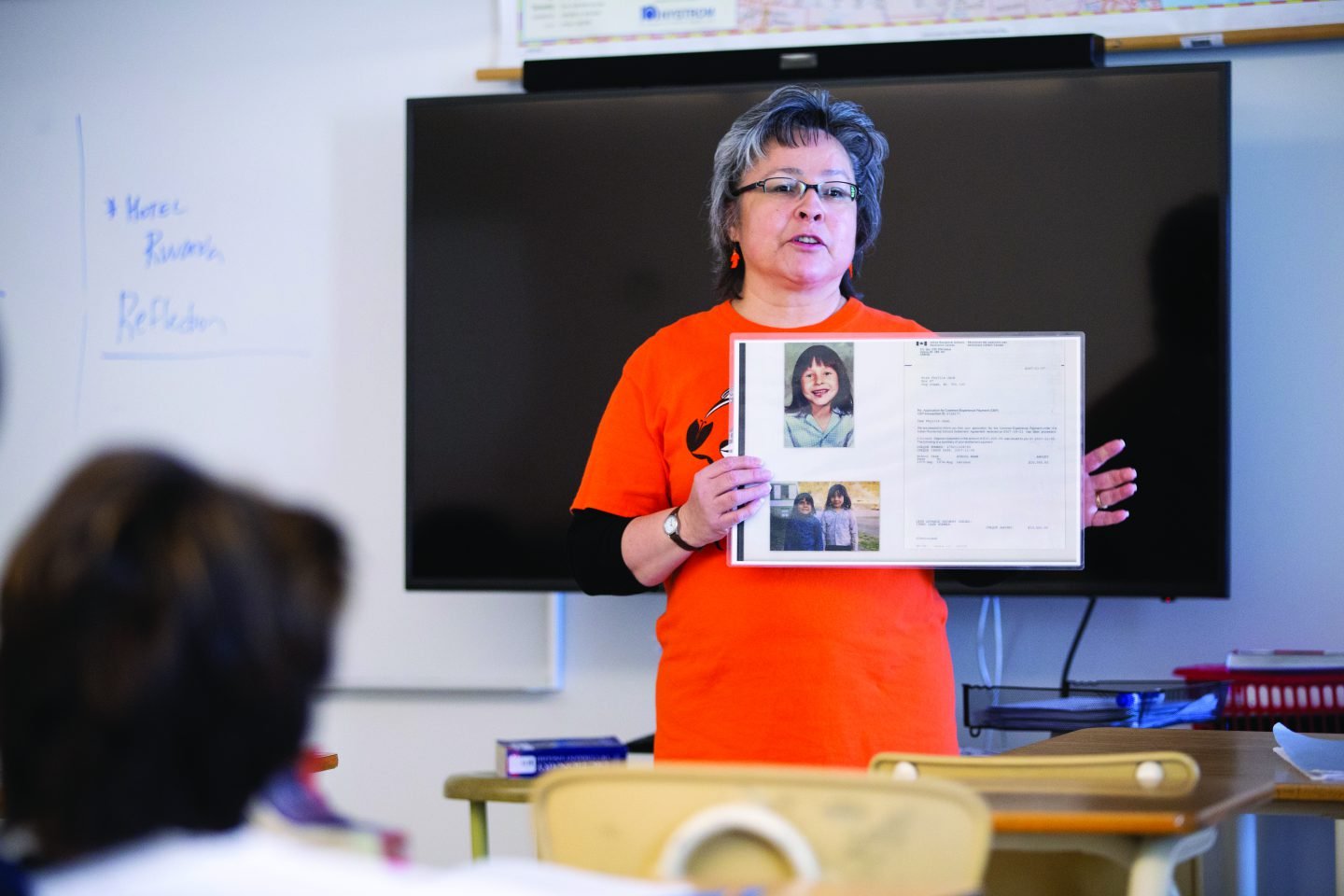

“A lot of students were asking me over the past few days if we were having the Phyllis Webstad from Orange Shirt Day to speak to us today,” says Meagan Lundgren, Altadore Elementary School’s assistant principal, to the students seated on the floor. “Please welcome the Phyllis Webstad from the Orange Shirt Society to talk to us about Orange Shirt Day!”

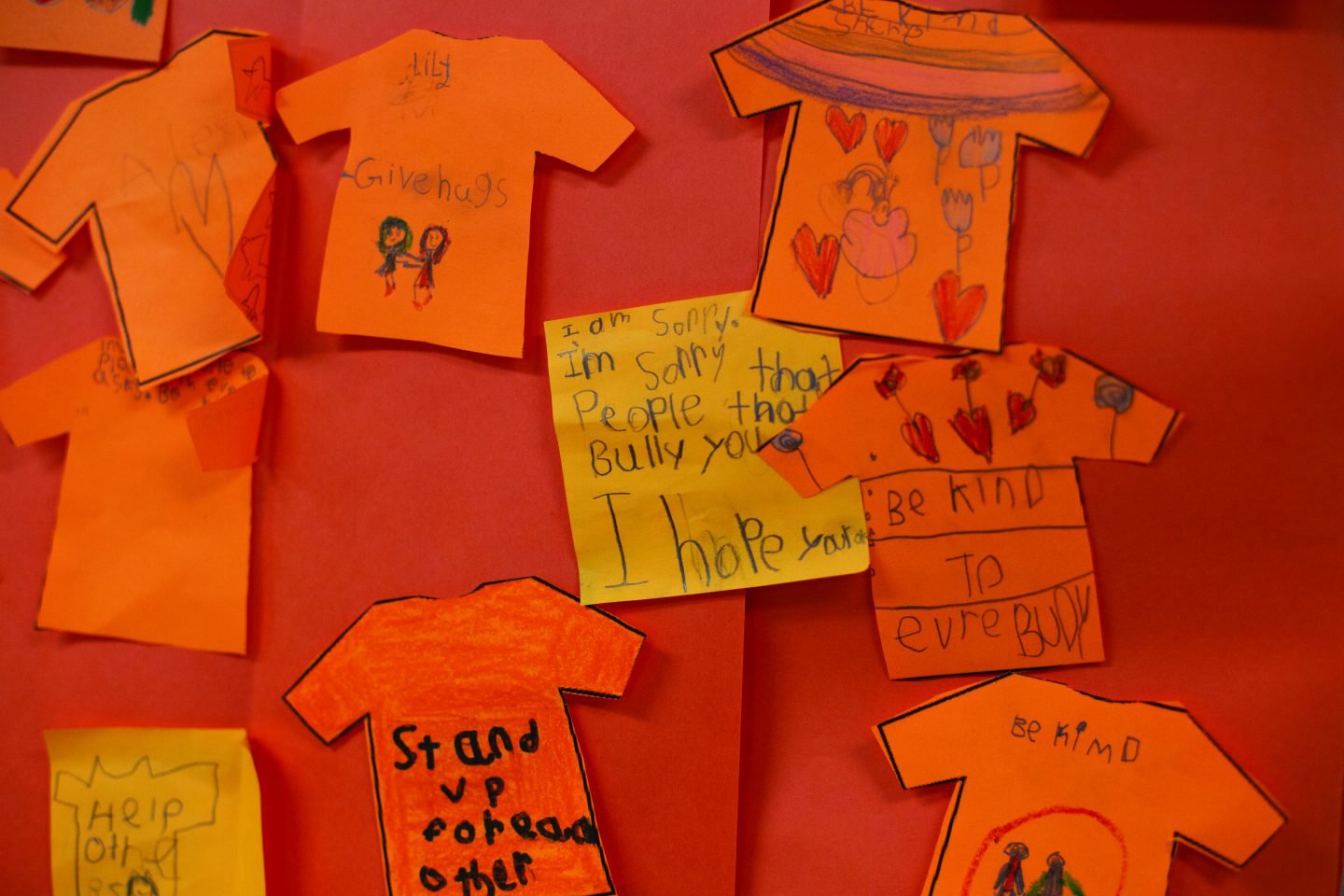

Clapping erupts and bright faces emerge from the roughly 200 students at the Calgary school’s assembly on a cold February morning. Shades of orange, from peach to pumpkin to paprika, are evident on all the bodies gathered in the gymnasium. There is both an innate curiosity and comfort between the children and their guest of honour.

Webstad is the creator of Orange Shirt Day, a grassroots movement that turned global a few years ago to commemorate the residential school experience and honour survivors. Since September 2019, she had been touring schools across the country to share her own experience attending residential school and the importance of Orange Shirt Day, part of a project called Paths to Reconciliation, a partnership between the Orange Shirt Society, Canadian Heritage and Canadian Geographic, to bring her story to Canadians. When the tour finished on March 31, Webstad had travelled from Halifax to Haida Gwaii, B.C., delivering her message of reconciliation in person to more than 6,000 students and 500 adults.

Orange Shirt Day started school-wide at Altadore on Oct. 30, 2018, with Principal Kelly Christopher, although a smattering of classrooms opted in the year prior. Teachers use one of Webstad’s two published children’s books, The Orange Shirt Story and Phyllis’s Orange Shirt, to introduce students to her experience as a six-year-old girl going to residential school.

From 1831 to 1996, over 130 federally funded, church-run residential schools were attended by more than 150,000 Indigenous children. The goal, as Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, so succinctly put it, was to “take the Indian out of the child,” or forced assimilation. It was a cultural genocide that has reverberated through generations of Indigenous Peoples through intergenerational trauma. Stories stolen, stories lost, stories too horrific to tell.

Born on Dog Creek Reserve, 85 kilometres south of Williams Lake, B.C., Webstad is Northern Secwepemc (Shuswap) from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation (Canoe Creek Indian Band). She lived with her grandmother, who in preparation for her first day of school in 1973, took her shopping for a new outfit. Webstad carefully picked out an orange shirt that was both bright and exciting, reflecting her feelings on going to a new school.

But when she arrived at St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School, just outside Williams Lake, B.C., her emotions quickly went from excitement to terror when her shirt was taken away from her. The shirt represented a piece of home, a piece of her heart and life as she knew it. This would be the first of many atrocities and traumas she would experience during her year away from her home on the rez’.

As Webstad begins sharing her story to the students in Calgary, she asks them how many have ever had a sleepover. Many of the students raise their hands.

“Can you imagine going on a 300-night sleepover? That’s what it was like for me going away to this school,” she explains.

Webstad’s path of speaking engagements, writing books and heading up the not-for-profit Orange Shirt Society is not what she envisioned for her life, especially now in her early 50s. This journey started over coffee with a friend in late April 2013 in Dog Creek Reserve, while Webstad was brainstorming what she was going to say at a media announcement for the St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School Commemoration Project the next morning. She had joined the planning committee and, as a residential school survivor of St. Joseph’s, she had been asked to speak at the kick-off of a week-long series of events across the country to coincide with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s efforts to begin to right the wrongs of residential schools. Thankfully, an idea came to her in the café, coffee in hand.

“I know what I can talk about. I can talk about my first day, when Granny got me my shirt,” she says she told her friend Joan Sorely.

No sooner were those words out of her mouth than Webstad broke down. It was a deeply personal story that she had never shared before, not with her husband, nor with her children. Armed with a message, Webstad now had a mission. She had less than an hour to check out local shops for an orange shirt to wear during the big announcement.

“I had nothing orange. I hate orange,” she explains. “I’ve always hated orange.”

The next day at the news event, much like her fateful first day at the residential school, Webstad was a bundle of nerves in her bright new orange shirt.

“I was to be a part of the media announcement,” she says. “So, there’s the Chief, and the mayor, and all these people with big titles, and there’s me, unemployed residential school survivor.”

But on April 24, Webstad courageously shared her story about the orange shirt that was taken from her. Little did she know, she was about to share her story with the world.

Joan Sorely, the first person ever to hear her story that fateful evening in the coffee shop, was on the commemoration project planning committee with Webstad.

“We were generating some momentum here about the horrors of residential school, and Phyllis’s story is so simple and yet powerful. And it’s pretty much everybody’s story. You know everybody [residential school survivors] lost their clothes on their first day of school,” Sorely says. “I was trying to figure out how we can keep this momentum going. And I thought ‘well, there’s Pink Shirt Day [to take a stand against bullying] — why don’t we have Orange Shirt Day?’”

And that was the genesis of Orange Shirt Day. Over the next two days, Sorely brought her idea to the planning committee comprising representatives from the Cariboo Regional District, B.C. School District #27, the City of Williams Lake, local First Nations and others. Webstad was absent that day but was approached via email for her permission to hold an Orange Shirt Day in the B.C.’s Cariboo-Chilcotin area. At the next committee meeting, they decided to have Orange Shirt Day there annually on September 30.

“We chose September because that’s when kids went back to school — that’s when they were taken away,” Webstad says, adding that it felt divinely guided. “[That fall] when I went to the TRC event in Vancouver, [I was] sitting there listening to the truths being told, and an Elder sitting not far from me was talking, and she said that September was ‘crying month’ — and I knew then that we had chosen the right day.”

“We chose [the slogan] ‘every child matters’ because I talked about how I felt that I didn’t matter when I was in residential school. No matter how much I cried, nobody cared. Nobody. We weren’t hugged. We weren’t consoled. We could be half-dead and we weren’t tended to,” Webstad shares. “Every child that went to residential school, well, they all matter. Even the ones that didn’t come home, they matter. And it wasn’t until after we were using that slogan that I realized that it fits the past, the present and the future. It fits reconciliation — it’s one of those divine things that fits in this day of reconciliation.”

On April 26, 2013, the idea of Orange Shirt Day was first presented in public at a professional development day for educators at B.C.’s School District #27. Presbyterian Minister Shannon Bell from Quesnel, B.C., happened to be there and was fired up by the idea. She approached Webstad following the event to ask if she could help her make Orange Shirt Day global.

“Go ahead, help make it global,” Webstad told her.

Webstad didn’t give it much thought after that. After all, it had only been a few days since she had first shared her story and the idea of Orange Shirt Day sprouted. However, five months later, when Webstad was in Vancouver for the TRC’s Reconciliation Week at the Pacific National Exhibition grounds, she was handed a brightly coloured orange flyer. The flyer read, “Orange Shirt Day September 30,” and continued, “Wear an orange shirt to honour the children who survived the Indian Residential Schools and to remember those who didn’t.” At the bottom, it directed people to an Orange Shirt Day Facebook Group and in script said, “poster done by Shannon Bell.” Webstad was floored.

“I look at this card and I’m like ‘What? What’s going on?’ Shannon’s making it global. They had thousands of these — I don’t even know how many — and they were handing them out to people at the TRC event, so it hit social media,” Webstad says. She then makes an explosion sound. “And then it blew up.”

Seated at the boardroom in her office in Williams Lake, B.C., where she now lives with her husband, Webstad shows me her scrapbook documenting the first year of Orange Shirt Day, all the while insisting that she’s really “not a scrapbooker.” She shows me just a smattering of the photos that were posted online in 2013. One photo shows a man in his 20s all the way in Italy, flexing at the gym while wearing an orange shirt in support of Orange Shirt Day.

From unemployed to overemployed, with no more time to scrapbook, Webstad heads the Orange Shirt Society with one part-time employee to help with administration at an office just 20 kilometres northwest of St. Joseph’s. During her year there, Webstad was bussed to a different school in Williams Lake to attend classes during the day and then brought back to St. Joseph’s at night to sleep. Fortunately, the following year, a school was established on Dog Creek Reserve, so she was able to return home to live with her grandmother and sleep safely in her bed again. Her mother and grandmother were not so lucky — they both attended the residential school all day for 10 years each. Parental visits were strictly forbidden, and they were only able to go home for one month each year. Ten years away, and only 10 months in their actual homes.

Webstad’s experience is just one story from one residential school pulled from a tangled web of thousands of stories.

“Everybody has a story,” Webstad says. “Orange Shirt Day is not just about me — it’s about everybody. For some reason, my story is the door opener, but there’s thousands [of stories].”

Webstad’s message is helping to alter the public consciousness to include the true history behind Canada’s colonial past. Over the past seven years, Orange Shirt Day has opened the door to conversations in classrooms, corporations and communities about residential schools, reconciliation, and the intergenerational impacts that reverberate across Canada.

In 2025, the first students who have had the opportunity to acknowledge and observe Orange Shirt Day since kindergarten will graduate from Canadian high schools. The Phyllis Webstad is particularly looking forward to the two 2025 graduating classes in Williams Lake, B.C., where her story will have transformed tragedy to triumph, one orange shirt at a time.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the May/June 2020 Issue

People & Culture

New project to educate Canadian students on the impact and legacy of the residential school system announced on Orange Shirt Day

People & Culture

Indigenous journalists are creating spaces to investigate the crimes committed at Indian residential schools, grappling with unresolved histories and a reckoning that still has a long way to go

People & Culture

Links to previous Canadian Geographic stories provide coverage and context

People & Culture

During Truth and Reconciliation Commission events, personal items were placed in a carved bentwood box to symbolize the journey toward reconciliation. How far have we come?