Kids

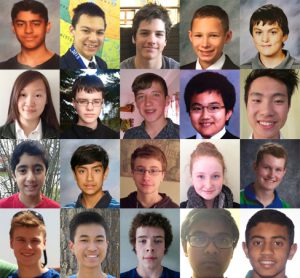

Meet the 2015 Canadian Geographic Challenge participants

The Canadian Geographic Challenge, now in its 20th anniversary year, will bring 20 young…

- 1691 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

History

St. John’s Ward, an area within Toronto’s tumultuous city center, has gone through many reinventions.

Once a densely populated slum that housed waves of Irish, Jewish, Italian, Eastern European, Chinese and African American refugees and immigrants, the notorious neighbourhood was expropriated by the city throughout the mid 20th century to make room for the Toronto General Hospital and Nathan Phillips Square, among other civic projects.

Now one of Toronto’s historically poorest neighborhoods is a bustling hub of metropolitan landmarks. But what got lost in the transition? The story of ‘the Ward’ shows what a poor job the city has done of understanding and preserving its own heritage, Mayor John Tory said recently.

Enter Kathryn Whitfield, a teacher at Northview Heights Secondary School at the corner of Bathurst and Finch. Whitfield has made it her mission as an educator to connect her students with their city’s history by having them do the work of historians, both inside the classroom and on the streets.

Using St. John’s Ward as a case study, Whitfield tasks her students with determining what should be commemorated by the city and how.

The students are first presented with archival material about the Ward and its residents: census records, photographs and Goad’s fire insurance maps. Whitfield said it’s exciting to watch the students’ perceptions of the neighbourhood change, particularly as they work with the maps and see streets and housing blocks that no longer exist.

“They start to peel back the layers of the onion… and look at patterns of continuity and change.”

Next, the students are given fieldwork missions that they must complete in the Ward, including taking photographs, making sketches and seeking out historic addresses. Ultimately, they face challenging questions about the ethics of the municipal decisions that reshaped the Ward, Whitfield said.

“The experiences of the people who lived [in the Ward] are so vital to understanding our city’s history and development,” she said. “It’s my job as an educator to give students opportunities to decide for themselves whose voices have been missed — or silenced.”

Whitfield received a 2015 Governor General’s History Award for Excellence in Teaching for her work, but said the concept of a historical thinking mission can be applied outside the classroom as well, for example by community groups.

“I truly believe the work of the historical thinking project can be done anywhere,” she said, adding it’s important to connect with local librarians, archivists, and residents in order to access primary source material and oral histories.

“If that engages your community in realizing the historical significance of a space, it will likely affect how decisions are made in looking at acts of commemoration and acts of remembrance.”

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Kids

The Canadian Geographic Challenge, now in its 20th anniversary year, will bring 20 young…

People & Culture

The daughter of a hereditary Mohawk chief and an English immigrant, Johnson used her hard-won celebrity to challenge Indigenous stereotypes

People & Culture

In celebration of its 90th year, the RCGS handed out awards to a diverse and star-studded roster of honourees

People & Culture

A group of students from around the world who embark on an unforgettable journey of Arctic education wind up discovering something about themselves in the process