Environment

Inside the fight to protect the Arctic’s “Water Heart”

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

- 1693 words

- 7 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Mapping

“I had much conversation with them regarding the source of the great river and regarding their country … they spoke to me of these things in great detail, showing me by drawings all the places they had visited, taking pleasure in telling me about them.”

—Samuel de Champlain, Les Voyages, 1613

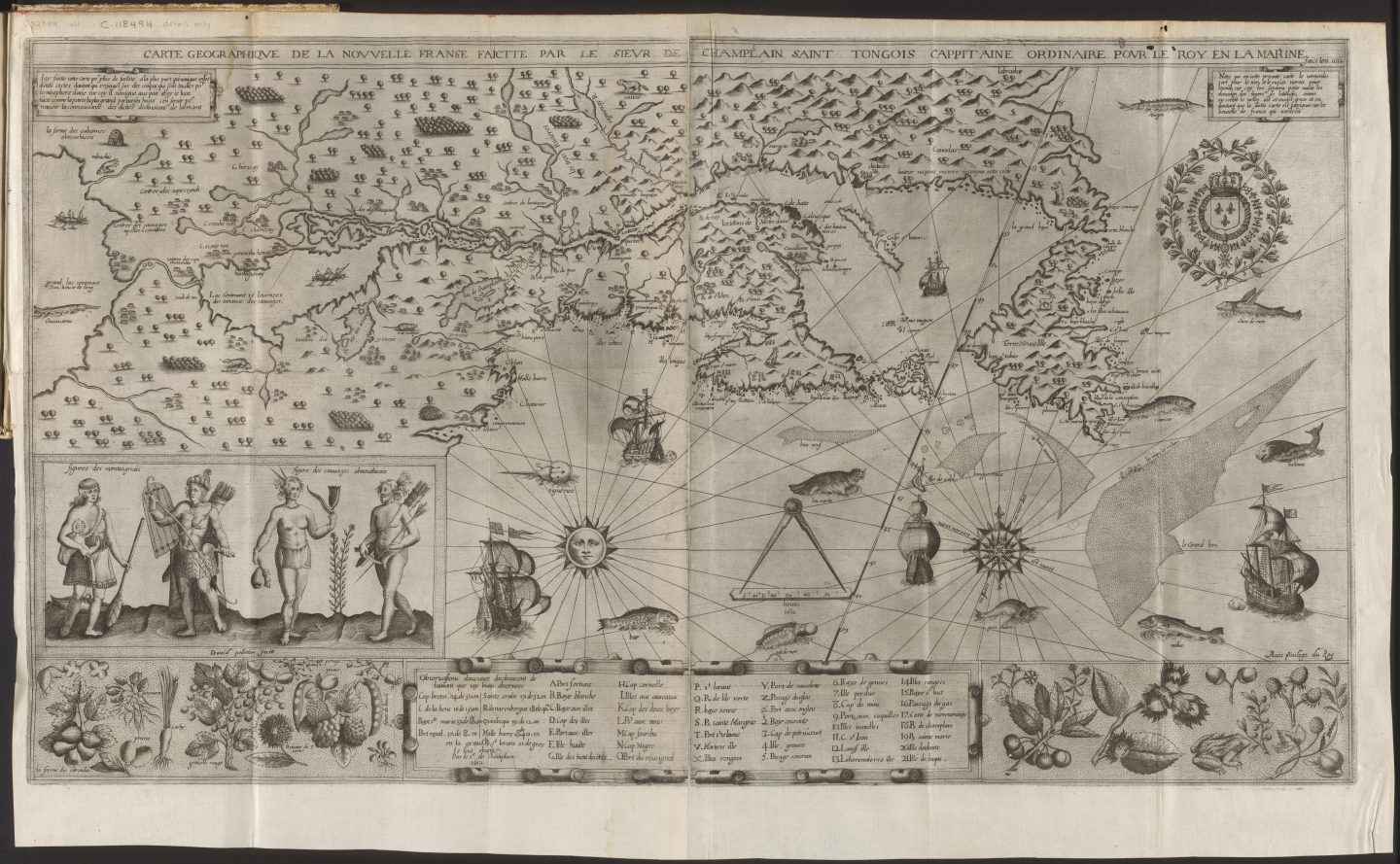

He may have been one of the greatest explorers and cartographers of his era, but Samuel de Champlain didn’t hesitate to give credit where it was due. He certainly does so in the passage above, which describes how the Huron people helped him navigate the wilds of New France and, ultimately, create maps such as the one shown above, Champlain’s first detailed depiction of the territory and one of the first to illustrate parts of the Great Lakes.

European explorers relying on Indigenous geographic knowledge wasn’t a new tactic. During Jacques Cartier’s voyage of 1541-42, for instance, Iroquois guides used sticks and twigs to show him the course of the St. Lawrence River and the location of rapids and waterfalls. But Champlain counted on Indigenous expertise like no other white man had. Whatever his motivations were — colonial glory, commercial riches, conversion of the “savages” to Christianity — Champlain knew that “the way to overcome physical obstacles to exploration was to become accepted by the Native people and learn to proceed with their help,” as Conrad Heidenreich notes in The Beginnings of French Exploration out of the St. Lawrence Valley: Motives, Methods, and Changing Attitudes towards Native People.

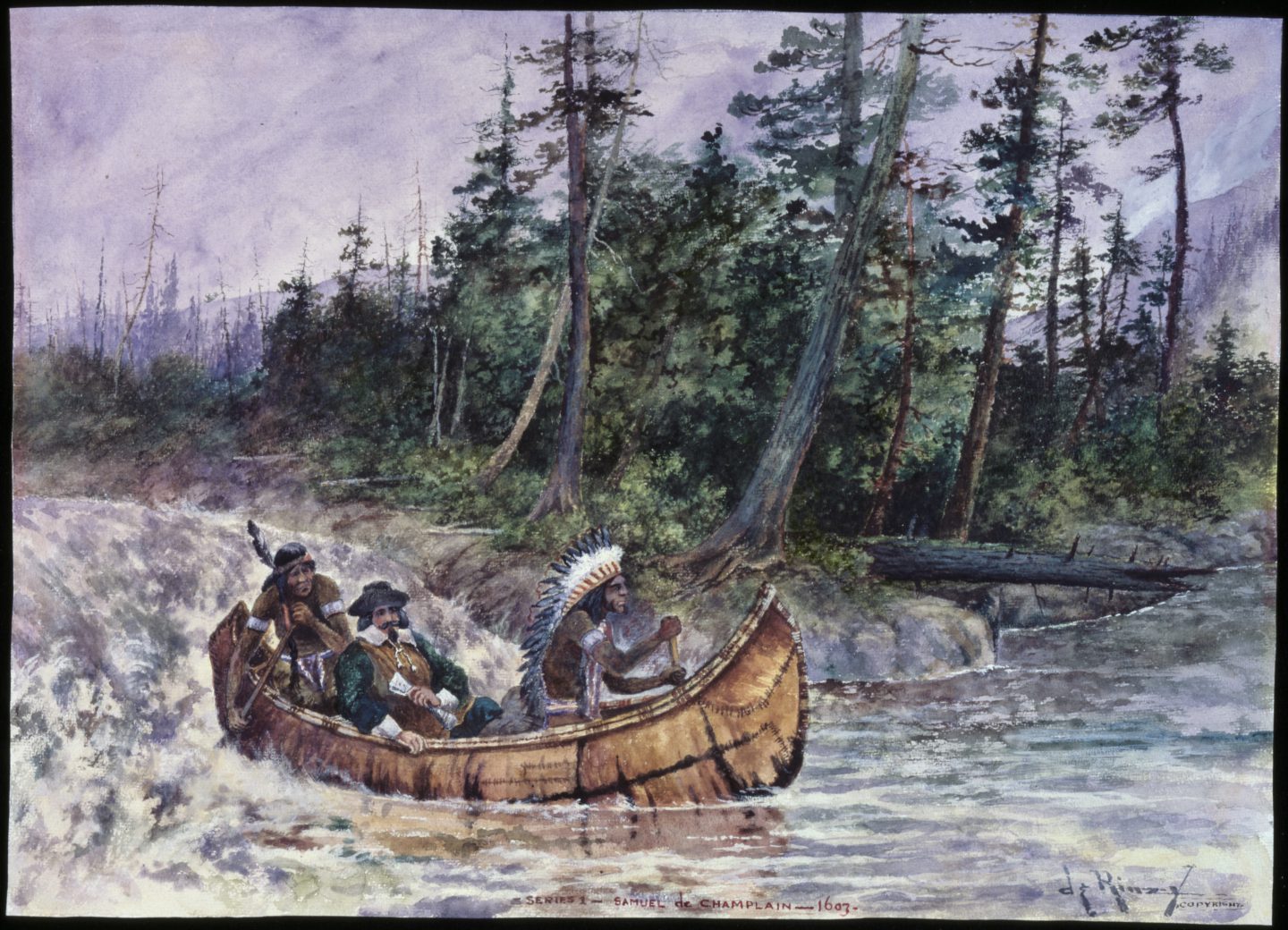

Doing so included treating some Indigenous groups as partners, adopting the use of the birchbark canoe (Champlain shot the Lachine Rapids with Indigenous companions in 1613, an event alluded to in the painting above) and asking endless questions. For example, much of what is shown along the St. Lawrence River west of the Lachine Rapids (labelled as “grand sault”) on this map he gleaned not from personal experience but from Indigenous accounts in 1603 — accounts that also contained descriptions of Lake Ontario and what could have been either Lake Erie or a composite of other Great Lakes. Champlain included both bodies of water on his map and illustrated each with manned canoes, noting the time it would take to cross the former — “15 Journees des canaux des sauvages” — and the length of the latter — “300 lieux de long.”

Were these and other delineations on the map imperfect? Of course — but that hardly seems to matter now. What’s more thought-provoking today is the spirit in which the information was shared, and whether Canadians can find some reconciliation-era wisdom in Champlain’s descriptions of how his Indigenous companions had continued to enlighten him. As he writes in Les Voyages, “I was not weary of listening to them, because some things were cleared up about which I had been in doubt until they enlightened me.”

*with files from Isabelle Charron, early cartographic archivist, Library and Archives Canada

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

How the Sahtuto’ine Dene of Déline created the Tsá Tué Biosphere Reserve, the world’s first such UNESCO site managed by an Indigenous community

History

A look back at the early years of the 350-year-old institution that once claimed a vast portion of the globe

People & Culture

Indigenous knowledge allowed ecosystems to thrive for millennia — and now it’s finally being recognized as integral in solving the world’s biodiversity crisis. What part did it play in COP15?

People & Culture

The director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation reflects on Indigenous progress in 2017 and looks ahead to 2067