Science & Tech

Elementary students find their sea legs with Canadian Coast Guard’s educational pilot program

The Adopt a Ship program took kids on a virtual behind-the-scenes tour with Coast Guard crews and staff

- 1430 words

- 6 minutes

People & Culture

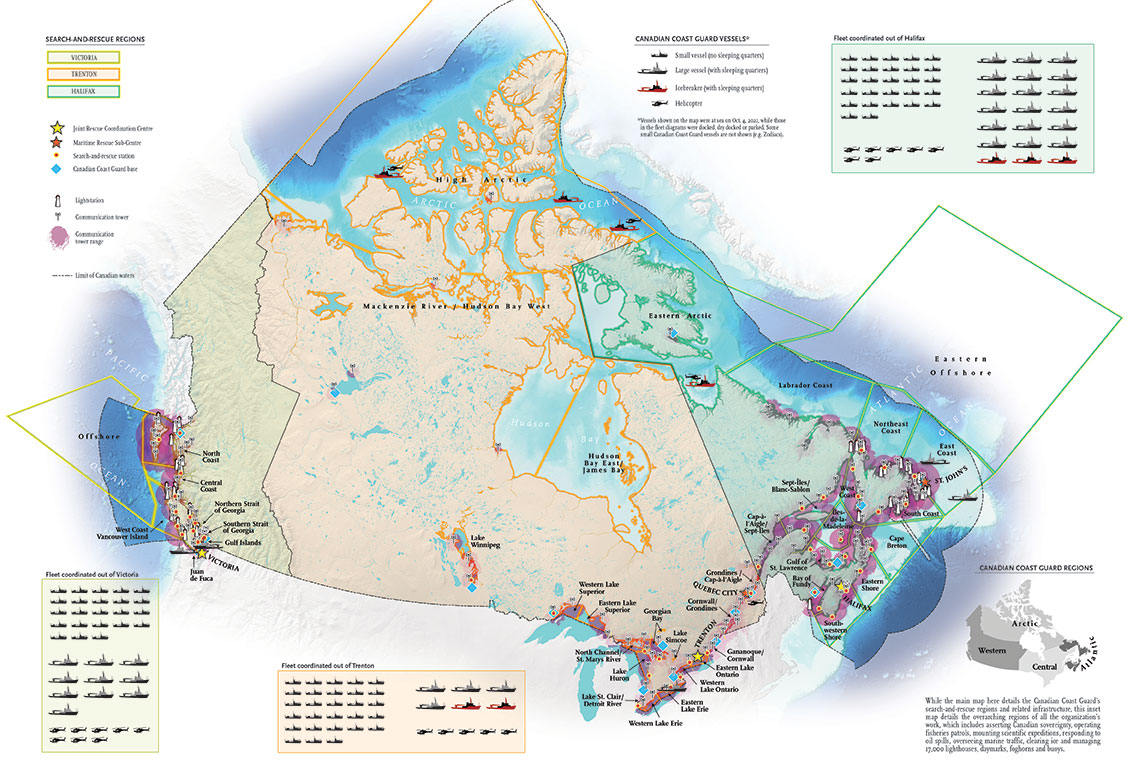

A celebration of the Canadian Coast Guard’s renowned search-and-rescue capabilities — and more — as the special operating agency turns 60

Rain skelters, winds fetch, waves swell.

Sometimes it’s a hurricane that stirs up and catches a yacht on the open ocean, sweeping a sailor overboard, but seafaring mishaps occur in every kind of weather along the 243,000 sinuous kilometres of Canada’s coastline — the longest in the world. Ships stray, foul a prop, run out of fuel. When the distress call comes, it’s the Canadian Coast Guard that answers.

The Coast Guard turns 60 years old this month. Anniversaries are occasions for both nostalgia and looking forward. They also provide a chance for Coast Guard commissioners — in this case Mario Pelletier, a 36-year veteran of the organization who took the helm in 2019 — to remind landlocked Canadians what they sometimes forget: “We’re a maritime nation. Coast Guard services are essential.”

They can bring big numbers into focus, too. The marine purview of the Coast Guard, a special operating agency of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, includes some 5.3 million square kilometres of ocean and inland waterways. Safeguarding Canadian waters and ensuring the well-being of all who fare on or around them involves an array of responsibilities mandated by federal shipping laws and the Oceans Act, Canada’s pioneering marine protection law. This immense undertaking includes everything from asserting Canadian sovereignty and doing fisheries patrols to mounting scientific expeditions and responding to oil spills. It means superintending marine traffic, clearing ice, and making sure our 17,000 lighthouses, daymarks, foghorns and buoys are doing the flashing, reflecting and keening they’re supposed to. More than 6,100 Canadians do the work, full-time, while thousands more volunteer through the Coast Guard Auxiliary. The budget for all this (for 2021-22): $1.775 billion.

Another number: 6,000. That’s how many search-and-rescue calls come into Coast Guard command centres annually, a number that represents the agency’s importance, working in close coordination with the Canadian Armed Forces, when it comes to emergency response. Across the country, that works out to an average of 16 incidents a day. While the Coast Guard provides an array of services to Canadians on every shore, the agency is perhaps best known for the life-saving work it does on the water.

It’s a lot of statistics. If you happen to be in St. John’s on the wharf by the Coast Guard’s Newfoundland base where the fisheries patrol vessel CCGS Leonard J. Cowley and buoytender and search-and-rescue ship CCGS Ann Harvey are tied up, the numbers can do what the looming ships do: fill up the view.

If you want to narrow the focus, consider the nearby coast. If it’s a midweek morning, during a September lull, let’s say, between buffetings by Hurricane Larry and Tropical Storm Odette, then maybe it’s bright and breezy, nothing to worry about. From this very government wharf, as modern and busy as it is in the present-day moment, you might lift your gaze to Signal Hill, where Guglielmo Marconi famously received the first transatlantic radio communication in 1901, historic in its own right and, in a Coast Guard context, marking the advent of Canada’s marine radio network. More history lies lower down — just out of sight — where Fort Amherst dominates The Narrows: it was here, in 1813, that Newfoundland’s first lighthouse was sited.

Back in the present, at the waking of the day, anniversaries approaching or not, the Coast Guard’s work goes on hour by hour. Inside the Newfoundland HQ, three floors up, in a room without a view, the Maritime Rescue Sub-Centre is on 24-hour vigil. Maritime search-and-rescue coordinator Ryan Gates and colleague Dwayne Munden are three hours into their 12-hour shift, keeping watch over Newfoundland and Labrador’s share of the country’s coastline — 900,000 square kilometres of ocean and nearly 30,000 shoreline kilometres.

First thing on a mid-September morning, there’s a fishing boat in trouble: fire has flared in the forepeak of a 20-metre long-liner, Miss Hanna. While the crew is safe and seems to have doused the flames, the boat is adrift, without power. The panic of the situation is as distant as the smoke and the fear of the fishermen and the desperation of what they’re going through on the open water off Hopedale, on the Labrador coast. Some 500 nautical miles (over 900 kilometres) away, Gates keeps his eye on the drifting icon representing the boat on one of four large screens as he confers with other fishermen in the area.

“You just get that initial adrenalin rush when the phone rings,” Gates will explain later. “You don’t know what’s on the other end. Then you just kind of slide into what you know, doing what you’ve been trained to do.”

The recent history of the centre reflects the weather — political and organizational — that has buffeted the Coast Guard throughout its history. Slashed out of operation in 2012 in a round of government budget-cutting, the St. John’s centre shifted its business — 400 calls or so annually — to the Coast Guard’s Halifax Joint Rescue Coordination Centre. Resurrected in 2018, St. John’s and its ocean 911 operators returned to work. As a situation demands, rescue coordinators can command aircraft and task Coast Guard ships, lifeboats and auxiliaries as needed. Under the Canada Shipping Act, they can even call in private and commercial vessels to help.

On the waves off Labrador, that’s what happens with Miss Hanna. “We went out with a pan-pan broadcast on the radio,” says Mark Gould, the St. John’s centre supervisor, “which is basically saying, there’s urgency, something going on, any ships in the area report your positions.” Another fishing vessel, Challenger 92, soon inches onto Gates’s monitors, to hook up a tow and head for port in the Labrador community of Makkovik.

A good ending in the early morning. But calls don’t always resolve so quickly or cleanly. “We do make it very high priority to establish connections with next of kin to the people that we’re trying to help,” says Gould. “We have some of these searches that last for days. We’re giving updates every hour, every few hours, at the very least — we’re going to build a connection with them on the phone. They’re going through something very traumatic. And we’re going through that same thing side by side with them, even though we’re professionals. It really kind of hits you hard sometimes, depending on the outcome of the search, it can be … I don’t know if stressful is the word … it can be deep. You feel it.”

Before the day’s out, the St. John’s centre answers four more calls. They’ll task the helicopter evacuation of an ailing crew member aboard the fisheries patrol cutter CCGS Cygnus and arrange for tows of a pair of disabled fishing vessels. They’ll respond to a call of man overboard, then stand down: false alarm.

Breezes stiffen, winters set in, squalls souse.

As they always did.

Canada’s maritime history is written in orders of wartime battle and in commercial bills of lading. It’s in charts disclosing shoals and reefs, currents and the migratory habits of Arctic ice. It’s hydrographic surveys and weather bulletins. It’s a register, too, of the names of countless ships and their fates: the schooner Reward, the cargo ship Douala, the ocean-going tug L’Aigle d’Océan, the container ship MV Zim Kingston. All of which, as it happens, were beset by one kind of peril or another on the waves, over the years, from 1872 right up to this past fall. All were attended by the Coast Guard or its forebears, because, of course, before 1962, there was no Coast Guard as such.

It’s true, too, that the history (just like the present and the future) is more than just ships. The first lighthouse to beam a Canadian caution was in Louisbourg in 1733. Official sovereignty and research voyages to the Arctic first set sail in the 1880s, the same period in which studies of Canadian tides and currents began to be formally organized. When it comes to Newfoundland, Britain’s parliament was discussing establishing a “waterguard” in the colony in 1792, though that was mostly to deal with smugglers.

Any lineage of coast guarding in Canada should probably pay respects to Jean Talon, intendant of New France, and the work he did in establishing shipbuilding in the 1660s. The history would also have to include Sable Island, the sandy fleck of an island that lies 300 kilometres southeast of Halifax. Situated in a famous fishing ground amid the busy mainstream of Atlantic shipping, it’s also beset by sandbars, fog and devious currents. Histories of its precincts feature phrases like “incidence of shipwreck” and “appalling miseries”; some 350 vessels are known to have foundered thereabout since 1583. Life-saving facilities were established on its shores as early as 1798, and these spawned so-called humane stations throughout Nova Scotia.

In Quebec, Trinity House was established in 1805 to oversee navigational lights and buoys along the St. Lawrence River. A historical sailpast would have to include the life-saving canoes that stood by with their crews between Quebec and Montreal in the late 19th century, the ice-breaking ferries that served Prince Edward Island, the lightships that marked the shoals of the Fraser River in B.C.

Figuring in, too, would be the flotilla of government ships drafted into service for dangerous duty in the Second World War: hydrographic surveyors, trawlers, lightships, quarantine patrol vessels.

Through the 1940s and into the ’50s, the story of marine navigation and safety often presents as a patchwork of agencies and jurisdictions, with an emphasis, increasingly, on the many gaps between them.

Calls for dedicated marine search-and-rescue grew as the years went on. There were petitions from coastal communities East and West, and on the Great Lakes, in newspaper editorials, by fishing and shipping groups. The B.C. government passed a resolution in 1953 calling for the establishment of a coast guard.

Nine years and several fearful maritime incidents later, the Coast Guard finally came into being — not long after a report noted that 13 different government departments were operating vessels in various capacities on Canadian waves.

In late January 1962, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s minister of transport, Léon Balcer, rose in the House of Commons to herald the news of the transformation of the Canadian Marine Service, including the Department of Transport’s fleet of 241 icebreakers, weatherships and lifeboats. The new Coast Guard was also promised a new colour scheme: red-and-white branding would replace black-white-and-yellow. And there would be fresh uniforms. “They will include berets,” news reports advised.

Seas subside, sunfish sport, engines idle.

“This job,” Darryl Taylor says quietly, “is 99 per cent boredom and one per cent horror.” Between calls to duty from the St. John’s rescue centre, Captain Taylor and his crew aboard CCGS Sacred Bay are cruising the waters of Newfoundland’s Conception Bay.

Taylor, who’s in his mid-50s, is the commanding officer of Sacred Bay, one of seven search-and-rescue lifeboats stationed around the province, and part of a national fleet of 42. He’s friendly and voluble, and, if you meet him, maybe spend an afternoon aboard his lifeboat as he puts it through some paces, you’ll begin to understand that the skills and singular instincts, the knowledge and experience that he and his crew wear as unobtrusively as the anchor tattooed on the back of his left hand, are as much a part of the story as the next-generation high-endurance search-and-rescue vessel he’s helming.

Asked about the worst conditions he’s seen in his 38 years at sea, he pauses. “On the draggers, God only knows. I’m just trying to think, now, how would I explain it. You’d be out in 60, 70 knots of wind, [waves] probably eight to 10 metres — like 35-, 50-feet high.”

This was back when Captain Taylor was still fishing on commercial boats, with dragnets, for cod, haddock, hake. He’d be aboard a ship like Zondermere, 200 kilometres offshore in howling wintertime, as he tells it, “down north off the Labrador coast.”

“That’s probably the worst of the experiences,” he says, “when you’re getting all the wind and freezing spray, and the boat makes so much ice.”

Viewed from the wharf, the 19-metre Sacred Bay has the air of a muscular, purposeful, extremely capable Canadian flag. It has a top speed of 25 knots and an offshore range of 100 nautical miles (about 185 kilometres). A helpful spec sheet posted in the wheelhouse discloses that Sacred Bay can surge from stop to full-bore in 35 seconds and that it’s manufacturer-approved to operate in 7.5-metre seas and gale-force conditions. In the case of capsize, it’s built to right itself — though, Captain Taylor notes with the start of a smile, “some of the boys might retire after that.”

Named for an inlet atop Newfoundland’s northern peninsula, Sacred Bay still has a new lifeboat smell. It was built at a cost of $8 million in Wheatley, Ont., on the Lake Erie shore, and entered service in 2019, tying up at Old Perlican on Newfoundland’s northeastern Trinity Bay, one of three stations recently added to the province’s safety network.

Two weeks on leads to two off for the crews of four that alternate active-duty shifts at the base. Working alongside Captain Taylor today are chief engineer Jody Walsh and a pair of leading deckhands and lifeboatmen, Lorne Welcher and Jerome Delaney. They’re Newfoundlanders and veteran seafarers all, with long years of experience in the fishing industry and emergency services and, some of them, impeccable Coast Guard pedigree: Engineer Walsh is the son of Linus Walsh, the last lightkeeper at nearby Baccalieu Island before it was automated in 2002.

Captain Taylor hails from Burin, on Newfoundland’s south coast. He was out on Placentia Bay going back as far as he can recall. “We used to go out rolling around in the dories,” he says, “and sometimes some of the older people in the community would be going out cod-jigging and I’d tag along.” At 16 he got his first job on a commercial fishing boat out of Marystown. Since then, his career has taken him back and forth between the fishery and the Coast Guard. His experience in the latter runs to 30 years now — and counting.

Most of that time he’s spent on the water, though he has also worked ashore, including as marine superintendent. “I’ve got to see it from both sides,” he says. “I enjoyed my couple of years in the office; I enjoy my time on the water better.”

Making wake on Conception Bay, Captain Taylor opens up the throttle and cruises north, getting up to speed, then ruddering hard over to show how smoothly Sacred Bay turns. How does Sacred Bay compare to lifeboats he’s worked over his Coast Guard years? “You can take more weather,” says Taylor. Better range, more speed, superior comfort: “This is like you’re living in a different world.”

“People ask me, what was the 47 like?” he says of the previous generation of Coast Guard lifeboat. “A small boat inside, right, you never had a big lot of room. I used to say, well, get into a clothes dryer, turn off the heat, and turn it on. When you get out after 12 hours, let me know how you feel. That’s the definition of a 47.”

For all the upgrades, Captain Taylor maintains perspective. “You got to remember: they’re still only a boat, and you’re on the water, and Mother Nature is in control. You got to know your limitations.”

The CCGS Cape Fox that Taylor previously commanded on Newfoundland’s western coast, at Lark Harbour, near Corner Brook, was a 47. It was aboard Cape Fox that he answered the most challenging call of his career.

It was 2012 in the fall, a beautiful morning, though the forecast was darkening. Taylor remembers the sailboat he watched depart the harbour. “There was an elderly gentleman in Lark Harbour, used to come over every now and then and have a little conversation with us. He was a fisherman from there. And he looked at me and said, ‘Skipper, you’ll be looking for them before today is out.’ He said, ‘They’re calling for an awful gale of wind.’”

Sure enough, at three o’clock the following morning, in came the predicted search-and-rescue call: man overboard.

“It was blowing 40, 45. And we had about six-, seven-metre seas.” Go — or wait for better conditions? The call was Taylor’s. “If it’s too bad for me to go,” he says, “and I can’t guarantee that I’m going to come back, instead of the person being in trouble we’re going looking for, I’m putting myself and the crew in trouble, too.”

Coordinating with the Halifax centre, Taylor said he’d nose out, take a look. “I got the updated forecast, and the wind was supposed to be dropping out.”

“So, me and the crew, we got outside of South Head, and like I said, it was blowing. But I knew I was going to have the wind on my stern, which wouldn’t give so much of a pounding. And we all had a little discussion and I said to them, I said, ‘Well, I feel comfortable going, and if the wind and the swell don’t drop out, we’ll just continue on down towards Stephenville and we’ll go in under the land and we’ll wait it out.’ So, we proceeded on.”

Heading south, Taylor had two of his crew members looking out the back window, watching for swells.

“When they roll down, I give her a little bit of power so that she wouldn’t roll on top of us. And as we proceeded down, the wind started to die out and the swells started to die out.”

The sailboat was safe and managed to make harbour; the search for the lost sailor went on for hours. Taylor’s Cape Fox had to turn back to refuel and was returning to the effort when word came that a Canadian Forces Cormorant had found him, lifeless.

Taylor pauses, refocuses. In a search, he says, in foul weather, “your mind is forever racing. Always looking ahead to try to prevent something. At the end of the day, you aim to come back with what you went out with. I always said, ‘if we didn’t succeed this time, we’ve got to move on and probably hopefully the next time we can have a better outcome … Today we couldn’t help someone; tomorrow we might be able to.’

“That wasn’t a good result, but least a person was found so he could be returned to the family. At least a family would know where they’re to.”

Tides rise and fall, years, too. New channels open up ahead.

“I get very passionate about the Coast Guard,” says Commissioner Mario Pelletier, who became the first graduate of the Coast Guard College to reach the agency’s top job when he was appointed in 2019. “I call it the Coast Guard family,” he says. “It really is like a family.”

While that’s a reflection of the organization he oversees, there’s also a personal context. His wife, Carolyn Morelli, is a former navigation officer; the couple’s daughter, Kelsey Pelletier, is a recent graduate of the Coast Guard College who’s now serving as second engineer for the icebreaker and research vessel CCGS Amundsen. At one time or another, all three have served aboard the Quebec City-based icebreaker CCGS Pierre Radisson. “So, when I go aboard the Pierre Radisson … there’s something there.”

Navigating an ongoing pandemic, Pelletier is proud of the organization’s response and record: “We had no transmission cases on board our ships at all.” This past year, with the Coast Guard’s 60th approaching, the business carried on as usual. Beacons flashed, foghorns moaned. Calls came in to the rescue centre in St. John’s as they did to other centres from across the country’s waterways; Sacred Bay headed out on the waters of Trinity Bay.

The Coast Guard has assigned its anniversary a theme: “Navigate the Future.” Its mandate will continue to involve challenges traditional to the institution, like fleet renewal. Working to advance reconciliation and collaboration with Inuit, First Nations and Métis governments and organizations is another priority. And while focusing on Canada’s North isn’t exactly a new one for the Coast Guard, it is one that’s intensifying.

In his time as an engineering officer, Commissioner Pelletier sailed in the Arctic. Later, he served as assistant commissioner for the Coast Guard’s central and Arctic region, one of three traditional divisions of oversight that in 2018 became four when the Arctic, with its 162,000 kilometres of coast, was designated a region of its own.

“Isolating the Arctic region, I think, was the right thing to do,” he says, noting the puzzles — geographical, seasonal, logistical, climatic — involved in trying to determine how best to serve a region in which less than 14 per cent of the navigable waters have been surveyed to modern standards.

“This is a pristine environment,” says Pelletier, “and we want to protect it and we want to make sure we do things right, and that’s why we created the Arctic region.” In large part, he says, it’s a matter of being on hand to listen and engage. How do Indigenous leaders and communities see the Coast Guard operating in the Arctic? “We need to learn from them: they know.”

Developing resources across the Coast Guard spectrum, from icebreaking to search and rescue to environmental response, doesn’t necessarily mean replicating what’s in the rest of Canada. “The services we provide in the South, it took a century to build those services,” he says. “We can’t afford waiting a century to build the same services up in the Arctic.”

Instead, Pelletier wants to continue to exploit new technologies, like the digital positional awareness system AIS, and to use satellites to increase connectivity in the North. “Because we’ve been delivering the aids-to-navigation program one way for 60 years, doesn’t mean it needs to be this way going forward.”

The realities of climate change figure in the Coast Guard’s northern future, too, along with all the attendant issues of sovereignty and increased tourist and commercial traffic.

“We say it’s opening up: it’s true. But that doesn’t only mean open water. It means very unpredictable ice conditions.” Pelletier points out that in 2021, there was a prospect of late freeze-up pushing more multi-year ice from the High Arctic into the southern Arctic where it is far less common. Since multi-year ice moves more slowly than first-year ice, and can be razor sharp, navigating it is less predictable and more dangerous.

Besides developing regions and modernizing assets, there’s also the matter of human resources. “How we manage people, too, needs to change,” says Pelletier. “We need to be more diverse, more inclusive.”

With that in mind, Pelletier looks to his alma mater, the Coast Guard College in Cape Breton. Its heritage links to a short-lived Nautical School established in Quebec City in the 1850s. In the early 1900s, the Department of Marine and Fisheries supported a network of private schools for prospective Canadian seafarers.

Opened in 1965, the modern-day college originally made its home in a former naval base in Sydney. Enrolment that inaugural year was 40; then as now, the program was four years, offering courses in marine engineering and navigation matters both academic and practical.

“Providing a stimulating immersion in the philosophy of marine thought,” an overview of the college touted in 1968, “the cadet phase of the modern officer’s experience replaces the drudgery by which men with high potential capabilities were formerly obliged to fill their most impressionable years.”

As with the Coast Guard itself, the graduates were, in those years, mostly men. No more. Having made a campus move to a modern facility, just to the east, in 1981, the college now has 214 students enrolled in the officer training program. This year’s

incoming cohort numbered 73, the largest since 1982 — and, as Pelletier notes, it’s 40 per cent female. “It’s a huge step forward,” he says. “We’re going in the right direction.”

Climates change, conditions vary, risks abound. For Canada’s Coast Guard, the work goes on, day by day, in the spirit and under the mandate of the agency’s motto, Saluti primum auxilio semper: “Safety first, service always.”

As the Canadian Coast Guard heads into its 60th anniversary year, highlights from the agency’s work in 2021 give a sense of its important work.

January: CCGS Griffon and CCGS Samuel Risley open the season’s icebreaking on the Great Lakes and the Coast Guard’s brand-new offshore fishery science vessel CCGS John Cabot makes its way from Victoria to St. John’s via the Panama Canal.

March: In furious seas, FV Atlantic Destiny, an offshore scallop dragger, goes down south of Yarmouth, N.S., and CGS Cape Roger works with the U.S. Coast Guard and Canadian Forces aircraft to aid 31 crew members.

May: As 37 new Coast Guard officers graduate from the Coast Guard College in Sydney, N.S., the government announces it will be moving ahead with the construction of two new polar icebreakers.

June: A new search-and-rescue station opens in Victoria, with CCGS Cape Calvert taking up station.

August: A Coast Guard hovercraft, the CCGS Siyay, helps in the rescue of 14 people after a charter boat founders off B.C.’s Gabriola Island.

September: As the science vessel CCGS Amundsen continues a voyage through the Northwest Passage, scientists share news of a new species of nematode — a roundworm — that has been discovered on cold-water bamboo corals collected during past surveys in Davis Strait and off Newfoundland’s Grand Banks. Also that month: after a successful summer of work based in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, fully staffed by Indigenous students, the Coast Guard’s first inshore rescue boat station in the Arctic wraps up its season. Off Labrador, meanwhile, the cod-fishing boat Island Lady and its two-man crew are reported missing. After a 10-day search by Coast Guard, Armed Forces and the RCMP, the operation ends, sadly, without finding the missing vessel.

October: The Coast Guard, the Royal Canadian Navy and commercial ships respond in the Strait of Juan de Fuca as MV Zim Kingston, a container ship bound for Vancouver, catches fire and spills cargo, some of which contains mining chemicals.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

This story is from the January/February 2022 Issue

Science & Tech

The Adopt a Ship program took kids on a virtual behind-the-scenes tour with Coast Guard crews and staff

Environment

Initially targeted at visitors and locals in Tofino and Ucluelet, B.C., the CoastSmart program could save lives along all Canadian coasts

People & Culture

The story of how a critically endangered Indigenous language can be saved

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?