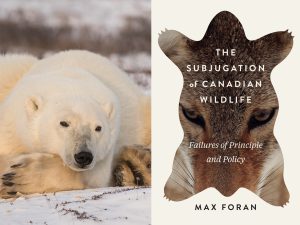

A population of polar bears in southern Hudson Bay that was previously considered stable has declined by 17 per cent in five years, new research has found.

The findings come from an extensive 2016 aerial survey of southern Hudson Bay covering an area of more than 5,000 kilometres. Compared to an equivalent study in 2011, polar bear numbers had dropped by almost a fifth.

“It’s not a surprise,” says Martyn Obbard, an adjunct professor in Northern Studies at Trent University, who led the research. Declines in sea ice mean southern Hudson Bay polar bears are spending, on average, 30 days more on land than they did in 1980. This affects the bears in two ways.

“It’s a double whammy,” says Obbard. “They have 30 fewer days to hunt and, on the flip side, they have 30 days longer when they’re on shore living off their stored body fat.”

This has resulted in an overall decline in the bears’ body condition, which Obbard and colleagues noted in a previous study in 2016.

“For polar bears, sea ice being available really equals hunting seals, which equals calories and healthier bodies,” says Alysa McCall, director of conservation outreach and staff scientist at Polar Bears International (PBI). PBI provided some of the funding for the study.

Polar bears are long-lived animals, living for up to 25 or 30 years in the wild, so it can take a while for long-term environmental changes, such as declining sea ice extent, to be reflected in their population numbers.

The study also found that while the number of cubs being born remained largely the same between 2011 and 2016, the number of yearlings had decreased.

Polar bears are induced ovulators which means that while females mate in April, the fertilized eggs will only implant in the uterus if the female’s body is in good enough condition by the fall.

“The suggestion, to me, is that females are going ahead, they’re implanting, they’re producing cubs, but then they can’t produce enough milk to raise those cubs successfully. And that’s why this large drop in the proportion of yearlings is a bit alarming,” says Obbard.

Another followup study is planned for 2021; if the current trend continues, the southern Hudson Bay polar bear population could decline by over a third in just a decade.

Worldwide, polar bear populations are expected to decline by 30 per cent over three generations, largely due to sea ice loss. Some projections indicate that Hudson Bay could be ice-free by the middle of the century.

“An ice-free area means a polar bear-free area,” says McCall.