Environment

Last bastion of ice

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

- 2894 words

- 12 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Wildlife

Only the bubbling of the Fishing Branch River and the delicate jingling of ice on the fur of a nearby female grizzly bear can be heard in this spruce forest in northwestern Yukon’s Ni’iinlii Njik Ecological Reserve. There isn’t even a click of a camera shutter as the bear inspects a pair of awestruck photographers, poised on a ramshackle platform of snow and fish carcasses, before galloping into the shallow water to pull out a fat salmon.

She is one of up to 30 grizzlies — the largest congregation of the species this far north — that gorge on the chum salmon that flood the Fishing Branch River (or Ni’iinlii Njik, Gwich’in for “where fish spawn”) each year from September to November. The salmon are drawn from the Bering Sea to spawn in this 12-kilometre stretch of river, which remains open year-round thanks to a pockmarked karst topography that percolates just-above-freezing, oxygen-rich water from the gravel river bed. Water freezes on the bears’ fur starting in October when the mercury dips below -20 C, and for a few weeks they become “ice grizzlies.”

Located within mountainous Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation Traditional Territory and surrounded by the roughly 6,500-square-kilometre Ni’iinlii Njik (Fishing Branch) Territorial Park and adjacent habitat protection area, the ecological reserve and neighbouring settlement lands protect a unique forest habitat and microclimate straddling the Arctic Circle that attracts species typically found farther south, including grey wolves, wolverines, eagles, moose, Dall sheep and the Porcupine caribou herd. For thousands of years, the region has been the cultural landscape for the Vuntut Gwich’in, who jointly manage the protected lands with the territorial government.

The reserve grants entry to just four visitors per day from September 1 to October 31 to protect the bears and their habitat. But for more than 10 years, guide Phil Timpany of Bear Cave Mountain Eco-Adventures has provided wildlife-viewing tours for handfuls of adventurous photographers.

By early November, the spectacle is over. The sun hovers close to the horizon, the visitors are gone, and the salmon, having laid their eggs, are dead. Fattened grizzlies, heavy with ice and fish, meander up the slopes of craggy Bear Cave Mountain to their denning caves to bed down until spring.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

What the collapse of the Milne ice shelf and the loss of a rare Arctic ecosystem might teach us about a changing planet

Wildlife

Salmon runs are failing and grizzlies seem to be on the move in the islands between mainland B.C. and northern Vancouver Island. What’s going on in the Broughton Archipelago?

Environment

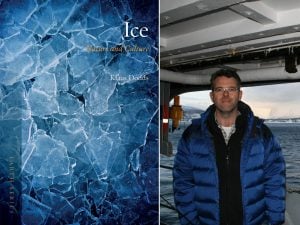

In his new book, Klaus Dodds delves into the fascinating natural and cultural history of ice

People & Culture

As the climate heats up, so do talks over land ownership in the Arctic. What does Canadian Arctic Sovereignty look like as the ice melts?