Environment

The sixth extinction

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

- 4895 words

- 20 minutes

This article is over 5 years old and may contain outdated information.

Wildlife

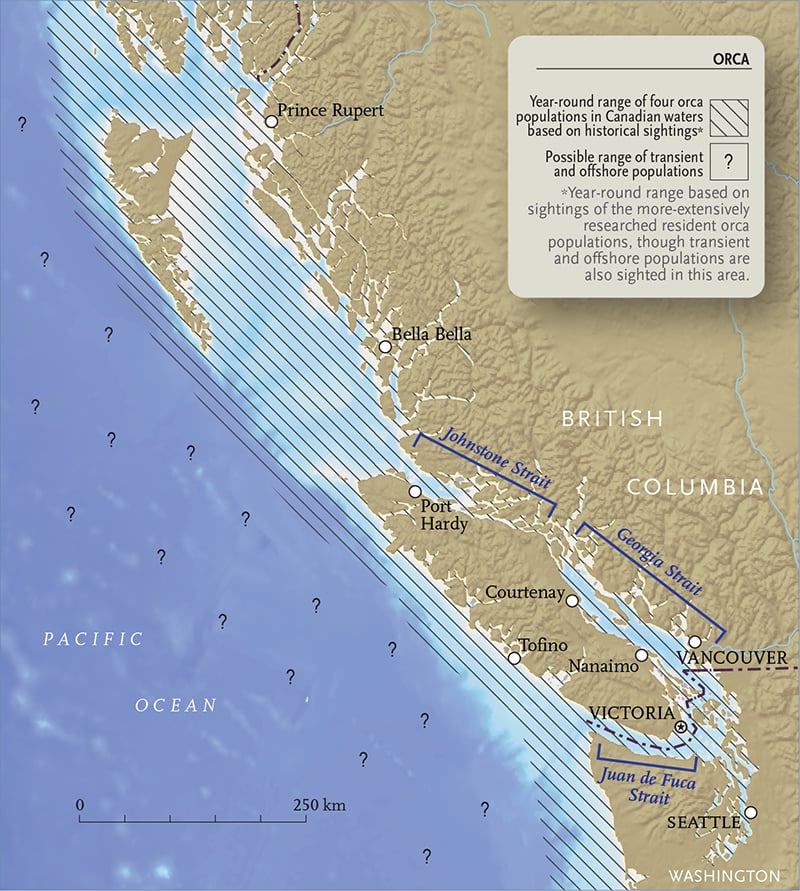

Researchers on Canada’s West Coast have tracked killer whales for 40 years, yielding important knowledge of their social behaviour, feeding patterns and critical habitat. There are four distinct populations of orcas along the coast of British Columbia: northern residents range from north of the Alaska Panhandle to Oregon; southern residents are found from southern Alaska to central California, with Juan de Fuca and Georgia straits being their summer habitat; Bigg’s killer whales (also known as transients) live in near-shore waters of Canada and the United States; and there’s a lesser-known group of orcas found offshore. Meanwhile, longer ice-free seasons are enabling more research on Arctic orcas, and sighting programs continue in the Maritimes. All Pacific populations of killer whales have been identified as species at risk, largely because of human-related threats.

Scientists are still trying to understand the effects of acoustic disturbances, such as boat traffic and sonar, on killer whales. “High-intensity noise reduces the range of killer whales’ communication and their ability to use echolocation,” notes John Ford, the head of cetacean research at Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Pacific Biological Station. “It all points to an impact on their functioning in really noisy habitat.”

The Exxon Valdez oil spill off the Alaskan coast in 1989 provided a glimpse of the effects of such incidents on killer whales. Following the accident, some local Bigg’s and resident killer whales “were never seen again and are presumed dead,” says Lance Barrett-Lennard, head of cetacean research at the Vancouver Aquarium. The subpopulation of Bigg’s common to the spill site is now a half-dozen individuals.

All West Coast orcas display concerning levels of toxic contamination. Former Fisheries and Oceans Canada toxicologist Peter Ross determined that the average male southern resident was twice as contaminated by PCBs — fatsoluble chemicals that disrupt brain, reproductive and immune systems — as the notoriously toxic belugas of the St. Lawrence River.

Both northern and southern resident orcas have evolved to feed primarily on chinook — likely because it’s the only salmon species present year-round in B.C.’s near-shore waters, explains Fisheries and Oceans’ Ford. When chinook numbers crashed in the late 1990s, both killer whale populations followed suit. Death rates increased by up to 300 per cent, suggesting the availability of prey is key to the species’ recovery.

Longer ice-free seasons led to increased whale sightings, which spurred Manitobabased Fisheries and Oceans research scientist Steve Ferguson to investigate the presence of orcas in the Canadian Arctic. Here, orcas target other whales, such as belugas, narwhals and bowheads. Satellite tracking has revealed that Arctic killer whales travel as far south as the Azores Islands in the mid- Atlantic. Ferguson says Inuit hunters have proven invaluable in getting southern scientists up to speed on regional orca behaviour.

Are you passionate about Canadian geography?

You can support Canadian Geographic in 3 ways:

Environment

The planet is in the midst of drastic biodiversity loss that some experts think may be the next great species die-off. How did we get here and what can be done about it?

Wildlife

An estimated annual $175-billion business, the illegal trade in wildlife is the world’s fourth-largest criminal enterprise. It stands to radically alter the animal kingdom.

People & Culture

Naming leads to knowing, which leads to understanding. Residents of a small British Columbia island take to the forests and beaches to connect with their nonhuman neighbours

Wildlife

Habitat loss, pollution, climate change have all contributed to steep declines of some species since 1970